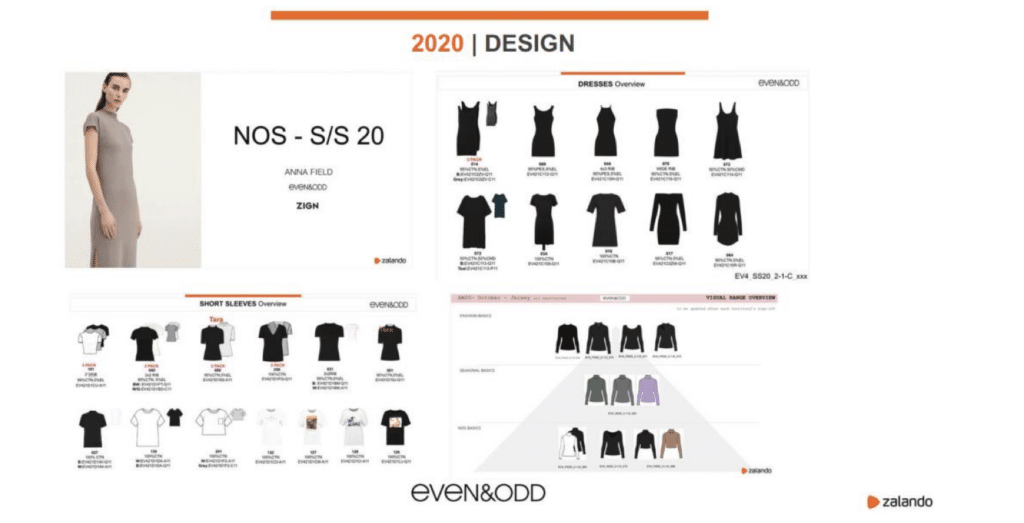

Zalando has beaten out a fellow fashion marketplace, which was looking to register a “confusingly similar” trademark for use on watches and jewelry, handbags, and apparel and footwear, among other types of goods. In a decision dated January 8, the United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (“UKIPO”) sided with Zalando in its bid to block Poizon Global Limited’s application to register “Even odds” as a trademark for use on goods in classes 14, 18, 20, 21, and 25. According to the UKIPO, Poizon’s “Even odds” mark is similar to Zalando’s existing “even & odd” mark and is likely to confuse consumers.

The Background: In response to Poizon’s 2023 application to register its “Even odds” mark, Zalando initiated an opposition proceeding, looking to block the registration of the mark on watches and jewelry (Class 14), handbags (Class 18), and apparel and footwear (Class 25). It did not take issue with the registration of the mark for use in connection with “leather, unworked or semi‐worked” in Class 18 and goods in Classes 20 (furniture) and 21 (homewares). Zalando argued that “Even odds” is visually, aurally, and conceptually similar to its own “even & odd” mark, primarily due to shared elements “even” and “odd.”

Moreover, Zalando asserted that that the goods for which Poizon applied (Classes 14, 18, and 25) are identical or closely similar to its own goods registered under the “even & odd” trademark. Due to the high similarity in the marks and the overlapping nature of goods, Zalando maintained that there is a significant risk that consumers might confuse the origin of their respective goods – either directly mistaking one mark for the other or assuming they come from related entities.

In its defense, Poizon (unsuccessfully) argued that its mark is different enough from Zalando’s for the average consumer to be able to distinguish between them. Additionally, it aimed to chip away at Zalando’s likelihood of confusion claims and narrow the scope of its asserted trademark rights by challenging both the similarity of marks and its proof of use of the mark on all of the goods listed in its registration during the specified five-year period (February 2018 to February 2023). For instance, Poizon argued that Zalando’s invoices and promotional materials only demonstrate use for certain goods, such as women’s clothing and accessories, rather than the entire range of goods listed in Zalando’s registration.

Poizon also pointed to potential gaps in Zalando’s evidence for goods, such as jewelry made from precious metals or coated with precious metals.

Zalando v. Poizon: Similar Marks, Similar Goods

Siding with Zalando, the UKIPO determined that there are similarities between the “even & odd” and “Even odds” marks in visual and aural aspects and varying degrees of similarity in terms of the goods at issue. Zalando established a likelihood of confusion, according to the UKIPO registrar, due to the similarity of marks and goods, even though the conceptual similarity was debated.

> The UKIPO registrar stated that in Zalando’s mark, the words “even” and “odd” are conceptually linked by the ampersand, whereas relevant consumers are “likely to perceive [Poizon’s] mark as conveying the expression ‘even odds’ (i.e., a situation where the chance of success is equal to that of failure). As such, the registrar determined that the respective marks are conceptually dissimilar. On the other hand, the registrar stated that in the event that consumers overlook the ampersand in Zalando’s mark, then the two companies’ marks are conceptually similar to a high degree.

Ultimately, the UKIPO granted Zalando’s opposition for goods in Slasses 14, 18, and 25, and Poizon’s application for the mark for use on these was refused. Meanwhile, the application was allowed to proceed for “Leather, unworked or semi‐worked” in Class 18 and goods in Classes 20 and 21, which were not opposed by Zalando.

TFL’S TAKEAWAY: In what might be one of the most interesting aspects of this relatively routine opposition proceeding, the UKIPO registrar discusses “fair specification” – or limits on the scope of trademark rights to the specific goods for which genuine use is demonstrated. Delving into this, the registrar stated, “A trademark proprietor should not be allowed to monopolize the use of a trademark in relation to a general category of goods or services simply because he has used it in relation to a few. Conversely, a proprietor cannot reasonably be expected to use a mark in relation to all possible variations of the particular goods or services covered by the registration.”

At the same time, the registrar noted that “it may be possible to identify subcategories of goods or services [that] are capable of being viewed independently,” and in which case, “use in relation to only one subcategory will not constitute use in relation to all other subcategories.” On the other hand, the UKIPO stated that “protection must not be cut down to those precise goods or services in relation to which the mark has been used, [as] this would be to strip the proprietor of protection for all goods or services which the average consumer would consider to belong to the same group or category as those for which the mark has been used.”

This is worthy of note as brands across the board continue to branch out beyond the goods/services that they initially offered up to complimentary goods/services. Luxury goods brands, for instance, are moving beyond leather goods and apparel to hospitality services; high fashion companies (like Thom Browne) are expanding to athleisure; and as has been the case for a long time now, companies are relying on more entry-level products, such as cosmetics and fragrances, during times of economic uncertainty.

Against this background, companies’ counsel will continue to argue that their trademark rights are more robust than the precise goods covered in their registrations.