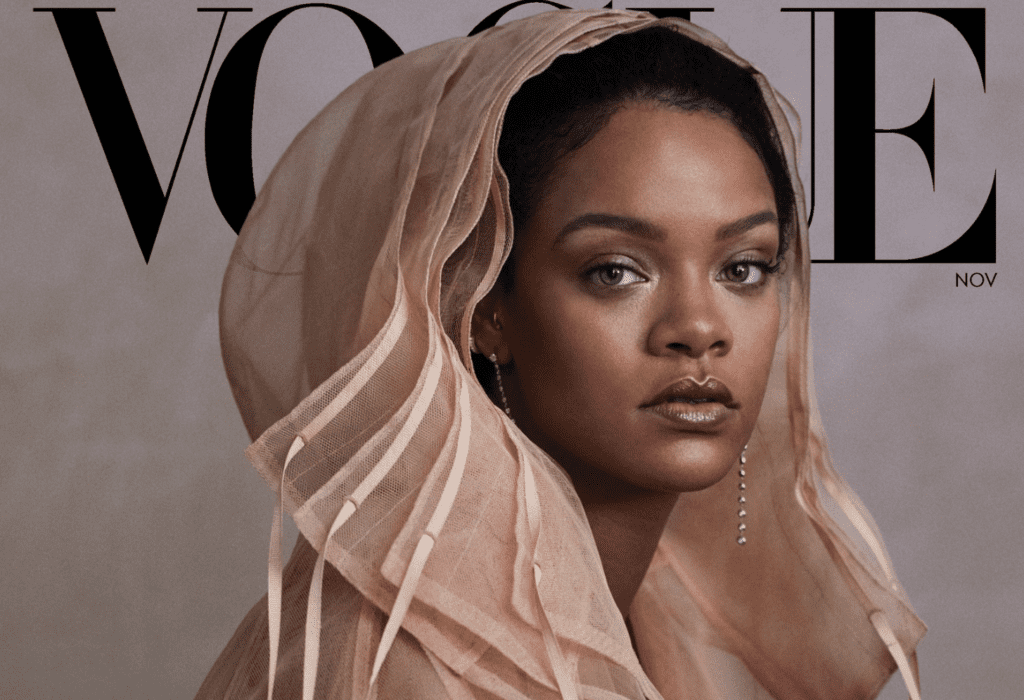

Since she launched her Fenty Beauty and Savage X Fenty collections, the former bearing some 40 shades of foundation, and the latter seeking to take market share from established lingerie companies by boosting sizes to include 42H bras and 3X undies, and focusing on a level of authenticity missing from this market, Rihanna “has done nothing less than upend the beauty and lingerie industries,” according to Vogue.

In its first full fiscal year, her beauty venture with LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned beauty incubator Kendo brought in nearly $600 million in revenues. Meanwhile, her Savage offshoot – which is similarly flush with sales, according to TFL’s sources – has scored $50 million to fund its expansion.

Now, Vogue’s Abby Aguirre writes, the 31-year old Grammy winner-slash-burgeoning retail phenom “is reimagining fashion at the highest levels” by way of her Fenty collection, a brand she founded this year with LVMH. Speaking of the Paris-based venture, one that has made her “the first black woman to lead a major luxury fashion house,” per Vogue, Rihanna says that her goal from the outset has been to create “honest” fashion. In other words, “I’m not the face of my brand, but I am the muse, and my DNA has to run all the way through it. I don’t want anyone to pull up my website and think, Rihanna would never wear that.”

Her website is, after all, “the only place you can buy the Fenty [collection wares] … most of the time,” Aguirre notes. That is, aside from the mega-star’s occasional pop-up shops, such as those that have recently set up in New York and Paris. In focusing on direct-to-consumer sales on a more flexible schedule (i.e., one that is not married to the industry’s set 4 main seasons, Fall/Winter, Spring/Summer, Pre-Fall, and Pre-Spring), Rihanna is shunning “the old luxury distribution model in favor of a Supreme-like ‘drop’ strategy” for her Fenty brand, which currently consists of a team of 44, including Jahleel Weaver, Fenty’s style director.

As for the collection, itself – which is 3 drops in, with the latest, what Vogue called “a reinterpretation of American office tropes” paired with “a graphic tee and a number of denim reworks that channel her own off-duty style,” coming smack-dab in the middle of Paris Fashion Week – it is “tonally idiosyncratic because—well, Rihanna’s style isn’t one thing.” Instead, “It’s kind of all over the place,” says Rihanna, “but I get it ’cause I’m all over the place.’”

Practically speaking, that means that her own outfits, as well as those being offered up by Fenty, can range from “tomboy one day … to a gown the next. A skirt. A swimsuit.” This range of aesthetics has given rise to what Aguirre calls a “conceptual hurdle: how do you translate Rihanna’s singularly diverse style into a coherent brand?” This is likely no small feat even, but maybe, it is exactly what fashion brands should be doing in order to meet the needs of the modern consumer, who is less brand loyal than in generations prior, ever-increasingly fatigued by the constant advertising-centric quests for their attention, particularly online, and prone to having a shortened attention span and demanding increasingly frequent novelty from brands, as prompted in part by social media.

Frequent drops of at-times seemingly unrelated garments and accessories tied together under the umbrella of a single brand has worked for Supreme, which landed a $1 billion valuation in October 2017 thanks to an investment from the Carlyle Group, and which does not appear to have suffered from what many projected would be alienation from consumers as a result of its new(ish) corporate roots.

While Vogue speaks to industry reception of the collection thus far, citing Dior creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri, for example, who says that “Fenty is proposing a new and extremely modern approach to contemporary fashion,” what goes unaddressed in its article is how Rihanna’s new fashion venture is faring from a sales perspective.

Fenty is certainly being touted both by industry outlets and finance-driven publications as a potential “major growth engine for LVMH,” and when it is compared to the bottom line of Fenty Beauty, whose growth was name-checked by LVMH as a catalyst for its perfume and cosmetics group’s 14 percent organic sales growth in 2018, such projections seem reasonable. However, it is worth noting, of course, that the success of and volume of sales for $18 lip glosses and $35 foundation, for example, tends to be vastly different than that of $800-plus deny corset dresses and $1,100 pinstripe jackets.

That is not to say that there are not more accessible and inherently commercially-successful pieces in the mix – i.e., those whose sales routinely pad the bottom lines of most well-established fashion brands – because there are. $190 t-shirts, scarves, high heel pumps, and jewelry round out the collection, making it difficult not to wonder when logo-bearing handbags, LVMH’s real commodity of choice, will make their debut.

Sales figures for Fenty’s sales have not been released, and chances are, they will not be, since LVMH does not break out revenues by individual brand, but instead, by its various divisions, such as Fashion & Leather Goods, as a whole.