Two landmark emissions bills are not the only ones that got the final approval in California this month. Governor Gavin Newsom also signed SB 244 – a right-to-repair bill that aims to “provide a fair marketplace for the repair of electronics and appliance products and to prohibit intentional barriers and limitations to third-party repair.” Specifically, the Right to Repair Act mandates that manufacturers of consumer electronics and appliances that are “manufactured for the first time, and first sold or used in California, on or after July 1, 2021” keep repair materials (from parts and tools to software and documentation) available for: 3 years after production for products within the $50-$99.99 price range, and 7 years for those priced at $100 or above.

Among the companies that will be most heavily impacted by the California Right to Repair Act? Apple, which initially lobbied against the bill but changed its stance this summer, saying that it supports SB 244 “because it includes requirements that protect individual users’ safety and security, as well as product manufacturers’ intellectual property.” The Cupertino, California-headquartered tech behemoth further stated in August, “We create our products to last and, if they ever need to be repaired, Apple customers have a growing range of safe, high-quality repair options.”

While the applicability of the new repairs law is limited to the makers of electronics and appliances (think: computers, televisions, phones, refrigerators, washers, dryers, dishwashers, air conditioners, etc.), it is difficult not to see some parallels with entities in other segments of the market, just as it is relatively easy to image more expansive right to repair efforts coming into play in the future. One of the most striking commonalities here comes by way of one of tech companies’ longstanding points of contention: their products are essentially too complex to be properly repaired by anyone other than licensed specialists.

At the same time, digital services and consulting company Infosys states that while customer repair is “arguably the most effective way to reduce environmental impact because products can be repaired at the customer’s own location, reducing the carbon footprint of the logistics required to return products to recycling centers and their processing,” manufacturers are concerned about giving customers access to repair parts/materials for fear of “loss of revenue as it cannibalizes new product sales.” They are also dissuaded by the potential “misuse or copying [of] technology, design, or intellectual property, and safety when hazardous materials are involved.” And still yet, Infosys notes that at least “some products are created with planned obsolescence in mind.”

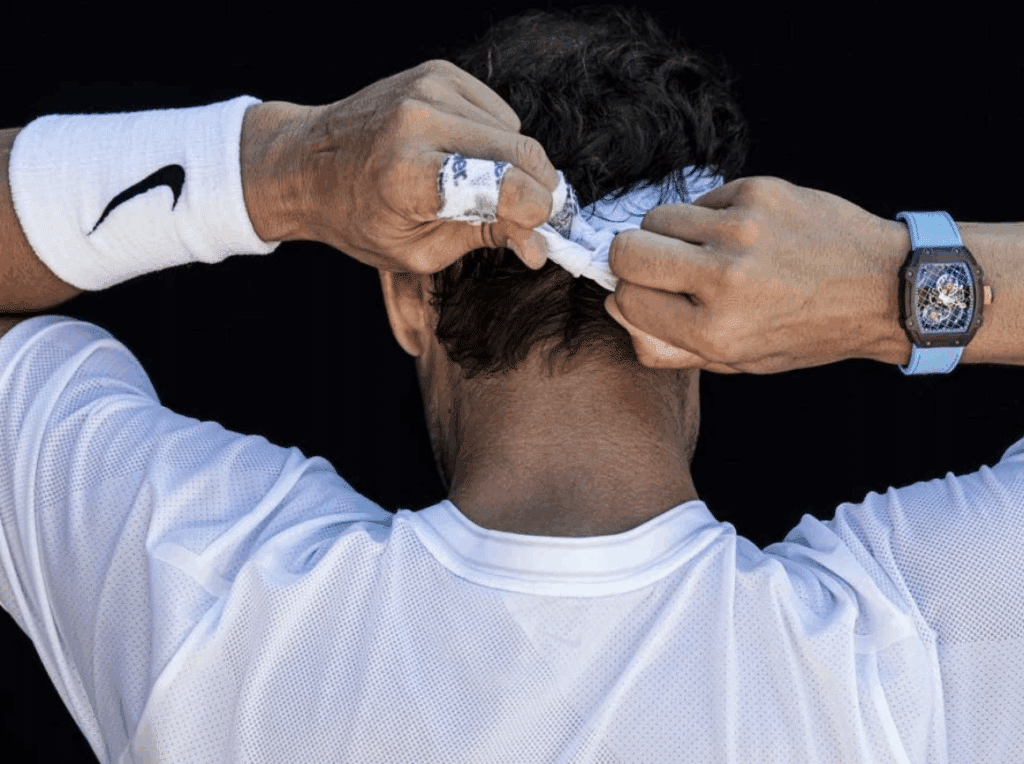

You could probably imagine a number of luxury watch companies making similar assertions to limit unauthorized repairs/refurbishments to their sophisticated timepieces. Like Apple, Microsoft, and co., “Brands such as Rolex, for example, often refuse to sell parts to unauthorized repair centers,” the New York Times previously reported. “And in some cases, watchmakers “actually may refuse to repair a watch that had been handled by an unauthorized center.”

Reevaluation of Repairs

The tides are undoubtedly turning from a legislative perspective. California’s Right to Repair Act joins existing state legislation in Colorado, Minnesota, and New York, which all passed laws in 2022 that endeavor to make it easier for owners to repair devices or to take them to independent repair shops. New York’s Digital Fair Repair Act, for instance, requires original equipment manufacturers to make tools, parts, and diagnostic and repair information available to owners of digital electronic equipment, as well as to independent repair providers. All the while, “several more bills are on the road to enactment,” Morrison & Foerster’s Julie Park and Will Baker stated in a note this summer, citing “at least 22 [other] state legislatures currently considering right-to-repair bills.”

Consumer demand is also rising, with public support growing across the country (and beyond) for right-to-repair laws that require companies to provide them with the same spare parts and repair manuals for products that have long been made available to authorized repair firms.

Against this background (maybe most pressingly, the need to comply with a growing number of states’ right-to-repair laws), companies appear to be waking up to the need to reevaluate their stances on repairs and the lifecycle of their products more broadly. As Los Angeles Times columnist Brian Merchant wrote this summer, Apple and co. “can see which way the wind is blowing.” In changing its tune on the California right-to-repair bill (and thus, right-to-repair more broadly given the might of the state and the impact of its law on the rest of the country), the iPhone-maker “probably fought for some friendly treatment in the amendment process, to protect its ability to authorize repairs and sell official parts.”

Apple “may also know that consumers aren’t as keen to buy a new phone every year or two, and that the repair business is growing – and may seek to consolidate its control over the market segment,” Merchant asserted, noting that “having watched this trend coming for years now, Apple has been building an industry lead on repairable devices, [and] by announcing its support of the right to repair, Apple gets to look like the good guy and perhaps get a jump on the competition, too.”

As for the impact that rising right-to-repair – and extended producer responsibility policies and regulations – and the corresponding extension of products’ lifespans will have the on the market for new products, Infosys claims that it will lower revenue from the sales of new goods.” However, this overarching movement may also serve as an opportunity for companies, including those in the luxury realm, to generate new revenue by way of “post-sale services, spare parts sales, upgrades, retrofits, exchanges, and end-of-life material management [that] could offset the impact in the long run.”