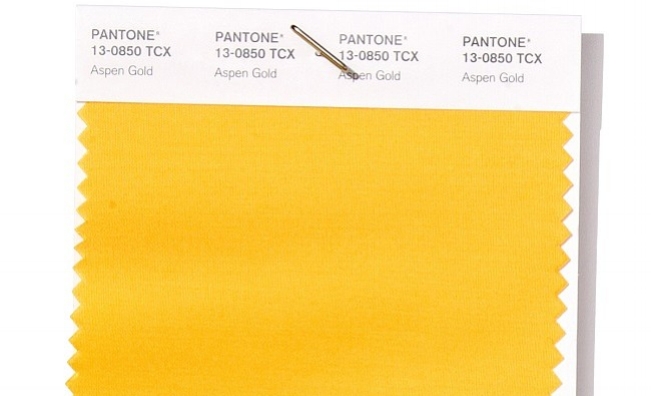

Ahead of the Spring/Summer 2019 shows, Pantone declared a handful of colors that would be the “it” colors of the season. Among them: Aspen Gold. The marigold yellow hue – along with an array of other shades – was part of the Carlstadt, New Jersey-based company’s pricey Spring/Summer 2019 Colour Planner, a “lifestyle color trend forecast that offers seasonal inspiration, key color directives, suggested color harmonies plus material and product application across men’s, women’s, active, color cosmetics, interior, industrial and multi-media design.”

The Colour Planner, which sets buyers back nearly $1,000 a pop, “enables [designers] to begin their seasonal color planning with the globally recognized Pantone Fashion, Home + Interiors color language,” according to Pantone . And judging by the start of the Spring/Summer 2019 runway shows, which kicked off in New York last week, that is just what no shortage of designers have done: looked to Pantone’s color forecasting for insight.

Founded in New York City in the 1950’s as the commercial printing arm of M & J Levine Advertising, Pantone is best known nowadays for creating a standardized and cataloged set of colors, and providing services to a wide range of companies in connection therewith, or as Pantone puts it, “helping companies make informed decisions about color for their brands or products.” For years, the company has released color forecasting-related materials for its ever-growing pool of customers, as well as its “Color of the Year,” a marketing campaign aimed at attracting new clients “in every industry where color matters.”

Unsurprisingly, no small number of Pantone’s clients are in fashion, an industry where color obviously matters.

While it has been the case for years, it is becoming increasingly obvious that a growing number of brands are relying very carefully on the information provided to them by the likes of Pantone – and other trend forecasting companies, such as New York-based WGSN – in order to calculate not only what hues will be most relevant for consumers in upcoming seasons, but also what fabrics, textures, textiles, prints, graphics, and other design elements are going to be of interest to the consuming public.

There is a reason, after all, that we consistently see brands turning out similarly colored garments each season or similarly cut silhouettes or even like-themed collections. Part of it may be cases of copying (as has been the large scale claim as of late), but it would be naïve to overlook the fact that many, many brands are all relying on the – same – information provided to them by trusted trend forecasting services.

image: Pantone

image: Pantone

The already Aspen Gold-soaked collections being shown for Spring/Summer 2019 are indicative of a larger trend within the practice of trend forecasting: the evolution of trend forecasting to trend dictating – and a greater revelation about the market more generally.

It could likely be argued that a sizable array of brands are taking the information provided to them more as dictations of what to show than forecasts of what could be to come. This is a point that has been raised in connection with Pantone’s “forecasts.”

“People always need confirmation. Even if you’re as strong as Zara, they need a start,” a member of Pantone’s anonymous color-selection team told Tom Vanderbilt, writing for Slate, in 2012. Mikel Cirkus, who heads the Conceptual Design Group at Firmenich, a flavor and fragrance company, similarly told Vanderbilt that the proliferation of garments and accessories bearing Pantone’s “it” colors after their grand reveal “is not a coincidence. It’s not even forecasting in my mind, it’s a dictating thing.”

Cirkus’s claim, if merited, would fit neatly in line with a larger trend in consumer goods creation, branding, marketing, etc. Consumer goods have always been dictated by the demands of consumers, at least to a certain extent, but in terms of fashion, this point seems to be in hyper drive in recent years. In the overly-corporatized landscape that is fashion in 2018, brands – especially those with shareholders to answer to – are increasingly risk averse and this sees them working to cater exactly to the whims of consumers.

As the Washington Post’s long-time fashion critic Robin Givhan wrote recently of the influx of shower slides, prairie dresses, fanny packs, biker shorts, and down-right hideous sneakers, brands are more aggressively looking to the consumers to “dictate lifestyle fashion.” In particular, brands are “taking [consumer] feedback and adapting the information and putting it back into the supply chain.”

Yes, brands are looking to adopt both specific products to meet customer preferences – and to avoid the off-loading of products at less-than-the-original retail price, thereby, avoiding a blow to their bottom lines, if successful.

Aided by the growing amounts of information available to them on the consumer (including age, location, salary bracket, buying habits, vacation searches, political leanings, etc.) paired with machine learning capabilities, brands – whether they be emerging designers in New York or conglomerate-owned brands in Paris – can … and are attempting to mitigate risk in a larger move to focus on their businesses.

As for whether this reliance on data and the prioritization of commerce over art is a bad thing, it certainly is not if considered from a revenue perspective. But if we shift the inquiry to a purely fashion design-centric one, the answer is different. As the New York Times’ Vanessa Friedman wrote this week, “There’s a lot of pressure these days to design by algorithm. We know too much about buying habits and likes, and the result is an insidious bias toward giving people what they have already indicated they want.”

“It may be safe, and easier to sell,” she says. But at the same time, it is “antithetical to the whole point of fashion, which should be about giving people what they never knew they wanted — what they couldn’t imagine they wanted — until they saw it.”