Interview magazine’s November 2014 issue included an striking editorial. Entitled “Pretty Wasted,” the spread – which starred with models Anja Rubik, Andreea Diaconu, Lily Donaldson, Daria Strokous, and Edita Vilkeviciute looking less-than-life-like – was nothing if not a thought-provoking one. While it may not have explicitly promoted violence, it does depict women as helpless victims, and given its inclusion in a mainstream(ish) magazine, we can assume that it sells magazines and/or clothes. Moreover, if taken out of context, as images are often portrayed and shared online – and especially on social media – the alcohol-infused editorial takes a markedly darker turn.

Interview’s spread and other ones just like it are confusing if we consider who, exactly, fashion caters to – most immediately – and who it is largely dependent on. Fashion is an industry that thrives on and thus, should cater to, women – and yet, it continues to victimize them. A few figures: As of 2016, the womenswear industry was worth a total of $621 billion dollars, compared to the men’s fashion industry’s revenue of $402 billion. As for the individuals within its ranks: Male models make about 1/10 of what females do. And save for many of the top positions, including chief executive and creative director roles, fashion is an overwhelmingly female-run industry.

Even with these stats in mind, fashion appears to be skewed against women quite a bit, and finds it to be rather “edgy” – or artistic even? – to depict women as the victims of violence.

More Than Just One Editorial

We cannot merely rely on a single editorial. Let us consider a few recent ad campaigns (Note: There are far too many editorials – such as Bulgaria-based 12 Magazine’s “Victims of Beauty” spread and Pop magazine‘s editorial featuring then-16-year-old model Hailey Clauson being choked by a man – to take into account).

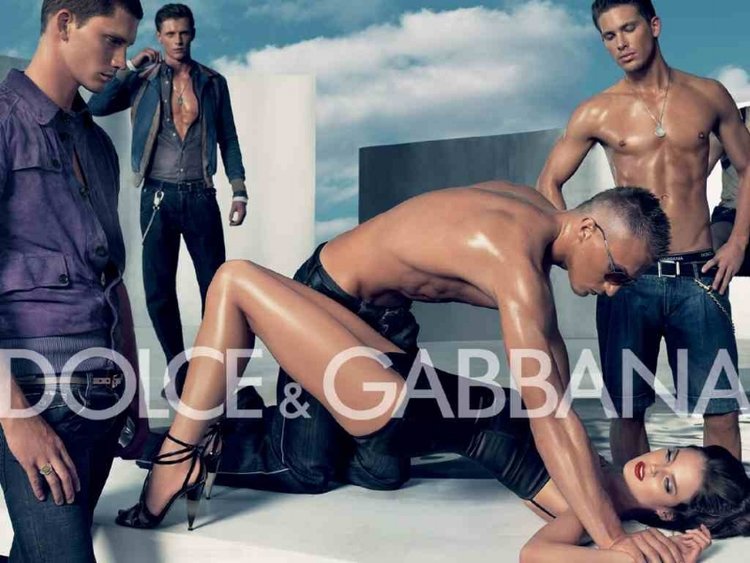

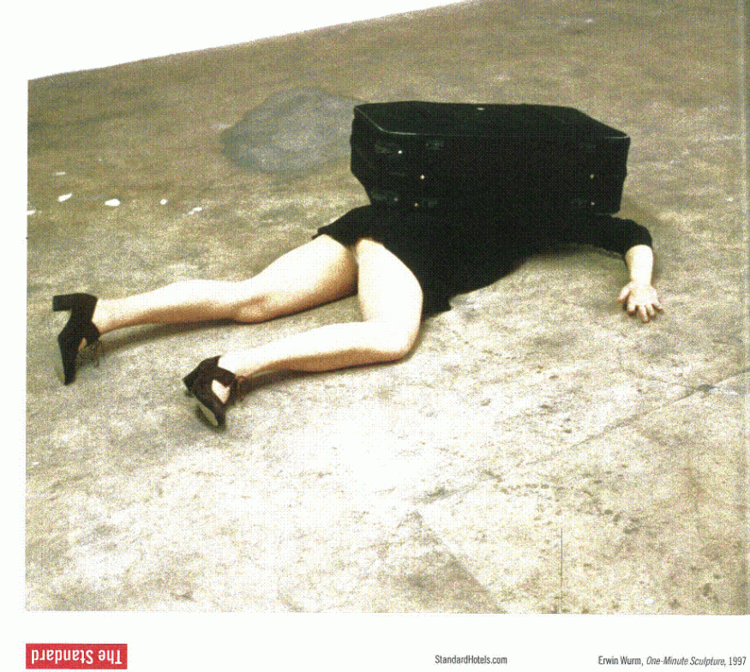

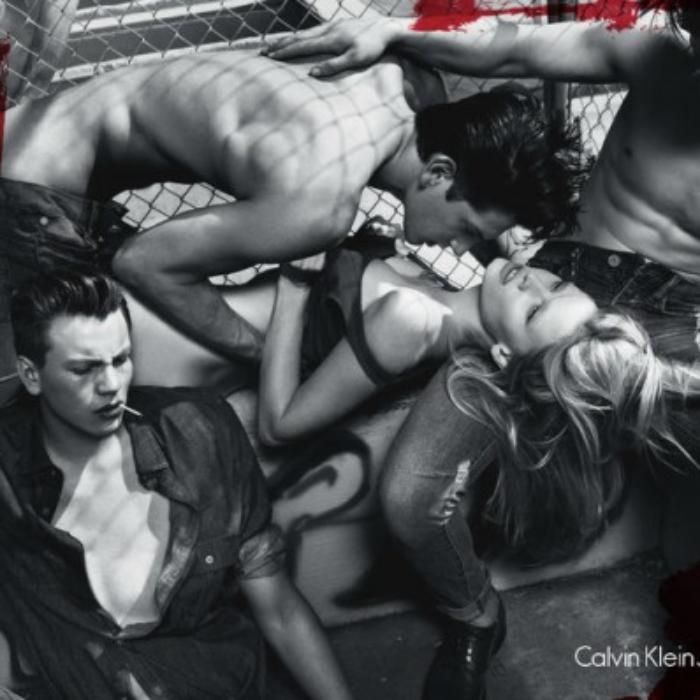

On the advertising front: There was Dolce & Gabbana’s controversial campaign, which has since been coined the “gang rape” ad (directly above). There was the similarly rape-themed ad that Calvin Klein ran for its jeans collection in 2010. There was also The Standard’s 2013 ad, which featured a women strewn on the floor and according to commentators, served to trivialize violence against women.

There is more, though. Do you recall Jimmy Choo’s Fall/Winter 2006 ad starring a dead Molly Simms in the trunk of a shovel-wielding Quincy Jones’ car? What about Marc Jacobs’ Spring/Summer 2014 campaign with Miley Cyrus, who was posed amongst what appeared to be a number of dead women?

Ah, and do forget the short film released in coincidence with Louis Vuitton’s Fall/Winter 2013 collection, which sparked controversy for allegedly promoting prostitution. Still yet, there was the uber-controversial windows that Barneys New York debuted in 2009. With red paint splattered all over the windows and mannequins posed as though they were (unsuccessfully) fending off attackers, the display – entitled, “Dressed To Kill” – was met with fury before it was nixed entirely.

Speaking at the time, Barneys’ creative director, Simon Doonan, said, “We encourage our display people to be creative. We give them a lot of latitude, but this clearly crossed the line. It’s as if someone saw a bad Hitchcock movie.”

Fashion or Art?

One thing these campaigns (and in Barneys’ case, windows) all have in common is that they portray women in unfavorable positions – whether they are dead, beaten up, about to be raped, or some variation thereof. What these campaigns also share is the fact that such treatment is being passed of as “Fashion,” which is unfortunately nothing new.

Photographers, such as Helmut Newton (who was behind the 1997 ad for Redial handbags, which featured a model holding a handbag in front of her face to shield it from a gun, for instance) and Guy Bourdin, just to name a couple, have long used violence as a theme.

Nowadays, the violent depictions appear to be occurring with marked frequency as a catalyst for selling pricey garments and accessories.

There is an array of popularly-cited explanations for why the fashion industry has an enduring fascination with violence. Put simply, some of these campaigns are opting for shock-value as PR. They are ads designed to shock and create controversy in order to gain traction and get you to remember them. Oftentimes, this is achieved by using violence or sex.

Others seem to simply confuse – or perhaps overlook – the distinction between art and advertising. Yes, there is a distinction, and it stems from the fact that the latter is a far more commercial medium. In relying on the fashion-as-art argument, the so-called guilty party (the fashion figure) is essentially saying he/she expects to be held to the same standards as art, where political correctness is not expected, let alone demanded.

This is the excuse The Standard looked to when it was called out for its violence-centric ad campaign (pictured below). The trendy hotel chain said its campaign was simply making use of the photographs of Austrian artist Erwin Wurm. But unlike art, fashion is – first and foremost – a consumer-facing industry, and the quantities of its products that are sold are markedly greater than those of even your most esteemed or in-demand artist.

With such facts in mind, it is not difficult to see why arguments are made to the effect that fashion should be held to slightly different standards than art.

A Reflection of the World?

More interestingly, however, is that others’ uses of violence in fashion are likely a reflection of what is going on in the world right now, as fashion – whether it be in the form of an advertisement, editorial and/or garment – is known to do.

Jeremy Scott, for instance, looked to current events as inspiration for Spring/Summer 2013. Entitled, “Arab Spring,” the collection – which included “riffs on Middle Eastern themes,” per Vogue – came on the heels of the series of the deadly protests and demonstrations across the Middle East and North Africa that commenced in 2010.

Raf Simons is also famous for tapping into the cultural zeitgeist ahead of America’s war on terror, which closely followed the 9/11 attacks. In a couple collections around that time, Simons made use of militant and rebel themes, including camouflage bombers and models whose faces were wrapped in balaclavas and/or covered in hoodies. As noted by Vice, Simons’ “Woe onto Those Who Spit on the Fear Generation . . . The Wind Will Blow It Back” collection, “conceived before the 9/11 attacks and the subsequent war on terror, and pre-dating the murder of Carlo Giuliani at the G8 Summit, was apt for a time of international unrest and angst.”

Similarly, violence against women is an unfortunate but undeniable reality. So, there is, of course, a chance that some of the aforementioned ads have served to portray an observation of the time in which we live.

If that is the case, it leads us to yet another inquiry: Does that make it alright?

The Guardian touched on the topic of the “fashion-forward” depiction of female corpses on the heels of the release of Marc Jacobs’ Spring/Summer 2014 campaign. The publication’s analysis of the matter, read, in part: “This obsession with death isn’t so surprising, when you consider it as the obvious and ultimate end point of a spectrum in which women’s passivity and silence is sexualized, stylized and highly saleable.”

The Guardian’s Kira Cochrane went on to make another point: “There’s a reason these images proliferate. If the sexualised stereotype of a woman in our culture is passive and vulnerable, the advertising industry has worked out that, taken to its logical conclusion, there is nothing more alluring than a dead girl.”

Death Sells

Following from this are some dark implications about our norms and motivations as a society but what may be worse is that brands are pushing off these images as fashion, as “edgy” fantasy scenarios, in order to sell stuff.

The backlash that followed Louis Vuitton’s Fall 2013 “prostitution-promoting” video sheds some additional light this industry practice. Inna Shevcenko, the leader of women’s rights group, Femen, spoke out about the video, suggesting that it was a mix of PR stunt and sex-sells advertising. Femen told the Huffington Post: “Once again, naked women are used to create a buzz or sell clothes.”

A piece in France’s Libération, on the other hand, said Vuitton’s video essentially relied on the ignorant glamorization of something that is not glamorous at all. “What indecency, ignorance and indifference to play with the fantasy of porn chic: the social condition of the vast majority of prostitutes has nothing enviable, nothing fancy, nothing happy about it.'”

Coupled with this is the underlying nature of the fashion creator vs. fashion observer dynamic. Most designers prefer that their clothes speak for themselves and in this same vein, editorials speak for themselves, as well, save for the accompanying text – which almost never explicitly takes on social causes. It is largely up to the audience to decide what to make of what they have seen.

But what about when the messages (inherent or completely obvious) are harmful? Does this change the “We Show, You Interpret” relationship between fashion’s creators and fashion’s observers? While it feels as though it potentially should, it probably does not, and so, in this way, these ad campaigns and editorials may aim to open the door for discussion amongst their viewers.

On the other hand, they may just be glamorizing violence against women as a way to sell more bags.