The Principal Register of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is relatively rife with trademark registrations for product configurations (i.e., marks that consist of the source-identifying appearance of a product, itself). The elements of Hermès’ Birkin and Kelly bags – which Hermès maintains trademark rights in and registrations for – come to mind. As brands begin to file trademark applications for the marks that they have traditionally used in a mostly physical medium (primarily on an intent-to-use basis) in light of the striking rise of the metaverse, one brand – Armand de Brignac or “Ace of Spades” – is proving to be an early mover, as it has filed trademark applications for registration for the appearance of its primary product for use in this burgeoning combination of virtual reality, augmented reality, video, social media, and the web.

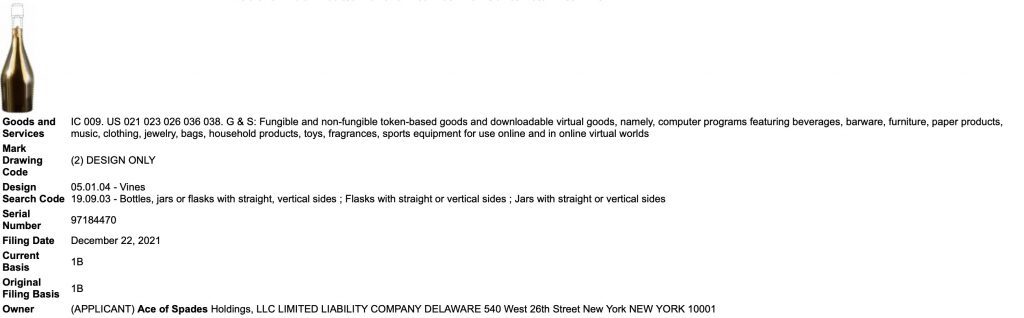

Looking to build upon its existing registrations, including one for “a three-dimensional configuration of a bottle in gold” that bears a “stylized spade design with a stylized letter ‘A’ and vine design on the neck of the bottle” for use on alcoholic beverages, namely, champagne, Armand de Brignac recently filed two more trademark applications for registration for the same mark – albeit for (prospective) use in the metaverse. Or more specifically, in the respective applications, which were filed on December 22, counsel for Armand de Brignac contends that the company intends to use the mark in class 9, namely, “fungible and non-fungible token-based goods and downloadable virtual goods, namely, computer programs featuring beverages … for use online and in online virtual worlds,” and in class 35, including “retail store services featuring virtual goods, namely, computer programs featuring beverages … for use online and in online virtual worlds.”

One of the interesting elements when it comes to Armand de Brignac’s applications – which are among the very first, if not the first, metaverse-motivated filings for three-dimensional configurations in the U.S. – is the issue of secondary meaning. Or more specifically, how do you evaluate or prove secondary meaning in regards to the metaverse? That would not likely be an issue for Armand de Brignac’s new marks, as they consist of product packaging and not product design. (Unlike product design trade dress, which is never inherently distinctive and is not registrable on the Principal Register without a showing of acquired distinctiveness, product packaging (including color marks) is often intended to – and actually does – serve a source-identifying function. As a result, such marks may be inherently distinctive, thereby, removing the need for establishing secondary meaning.)

Armand de Brignac might side-step the secondary meaning hurdle, but it is not difficult to imagine that secondary meaning will be a relevant consideration for other brands when they inevitably look to trademark protection for metaverse-centric uses of their products. With Ace of Spades’ pending metaverse-specific applications in mind, I could envision Gucci, for instance, filing a trademark application for registration for the virtual configuration of its Dionysus bag in classes 9, 35, and/or 41 on the heels of making intangible versions of the bag available to Roblox users to buy during its “Gucci Garden” experience on the platform last year.

Since the design configuration of a handbag would fall within the realm of product design trade dress (and not product packaging), Gucci would need show that the Dionysus design has acquired distinctiveness – a standard that can potentially be met by citing five years of consistent use of the mark and/or by providing actual evidence of acquired distinctiveness, including evidence of advertising expenditures, sales figures, unsolicited media attention, etc.

The question here becomes: Where does the secondary meaning to support Gucci’s hypothetical metaverse mark need to be achieved, in the “real” world or in the metaverse? If we consider a number of previously decided video game cases, which suggest that save for the issue of artistic relevance to a defendant’s work, real world trade dress rights can plausibly translate to other mediums, and the fact that a trademark holder’s rights in 3D configurations (i.e., “real” world products) can be asserted when they are reproduced without authorization in either in 2D or 3D, it may not be necessary to distinguish between use in the real world and use in metaverse when it comes to establishing secondary meaning.

“Just as trademark rights in 3D configurations can be asserted when they are reproduced in media,” Martin Schwimmer, a partner in the Trademark and Copyright Practice Group at Leason Ellis, tells TFL that the owner of trade dress in a handbag would presumably be able to “assert rights against an unauthorized 2D or 3D reproduction of that configuration in the metaverse for use in promoting handbags or selling them as artifacts.” In short: if a product has acquired distinctiveness outside of the metaverse, those rights very well may be enough to successfully claim infringement in the metaverse, no additional hoops (or trademark registrations) needed.

Ultimately, it is probably premature to consider what trademark rights will look like in the metaverse and how a brand might endeavor to show that its trade dress has acquired distinctiveness in the minds of consumers in connection with the metaverse given that is it unclear what – exactly – the metaverse will look like when it fully comes into fruition; it is just early days, after all.

In reality, the bulk of metaverse-focused trademark filings to date, including the lack of uniformity in the classes of goods/services that companies are citing in their mostly intent-to-use applications, or maybe better yet, their blanket approach to preliminarily filing across classes 9, 35, 41, and in a few cases, 42, as well, suggests that there is uncertainty at play about what the future will look like in this space, and that brands may be rushing to file applications when they do not necessarily need to.

Schwimmer states that brands appear to be “hedging” by way of the disparate classes they are filing for, which is an illustration that they are “not quite sure what they are going to do in the metaverse or how the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office is going to treat their applications.” However, at the end of the day, with regards to “a company’s main line of work,” he says that “its existing trademark portfolio will probably cover the most predictable of their activities in the metaverse. So, just as Nike does not need to file applications for shoes and shoes sold over the internet, they will not need to file for shoes sold via the metaverse.”

To the extent people are going to buy sneaker artifacts for their avatars, for instance, “then that would seem to be a class 9 downloadable item,” per Schwimmer, but again, questions remain on the trademark filing strategy front, and frankly, it might just be too early to tell what will be the most effective way forward for brands and their trademarks in the metaverse.