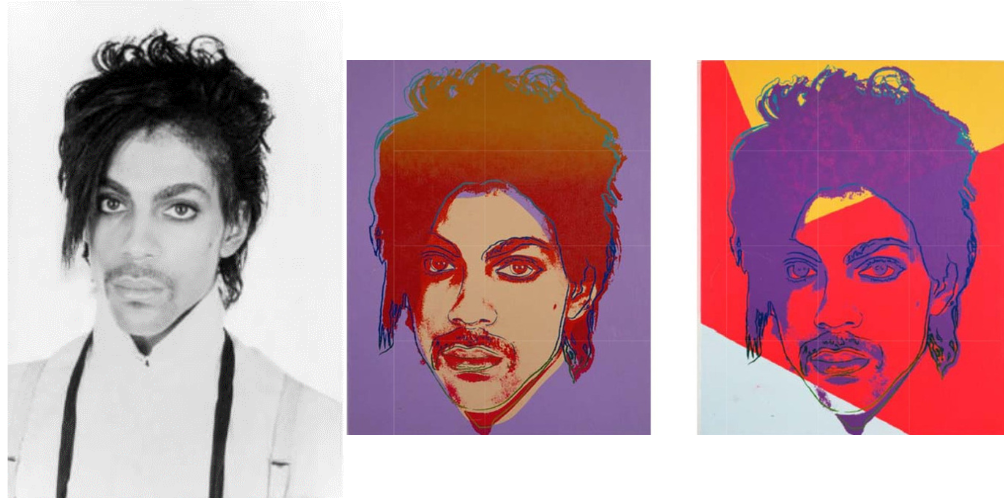

In a somewhat shocking decision handed down in March 2021, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled against the Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts in a copyright infringement suit brought by Lynn Goldsmith, a photographer whose photos of Prince were used by Andy Warhol to create artworks bearing his distinctive style and flair. In its defense, the Foundation claimed that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photographs amounted to fair use, but the appeals court held that fair use did not excuse the unauthorized use of the original photos.

What was shocking about the decision was that less than a decade prior, the Second Circuit ruled in a case involving artwork created by Richard Prince that the appropriation artist’s use of photographs of Rastafarian men taken by another photographer was fair use. In fact, the appeals court referred to Warhol works taken from photographs, such as his portrait of Marilyn Monroe, in ruling for Richard Prince. And in 2020, the Second Circuit held that music sampling of a portion of a Jimmy Smith song by Drake was fair use of the song because the sample – although taken note for note from Smith’s song – was transformative.

In the Goldsmith v. Warhol case, the Second Circuit seems to be having second thoughts about the reach of prior decisions, in which it found fair use. Not surprisingly, given this sudden turn of events, the Warhol Foundation appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In March 2022, the Supreme Court granted certiorari to hear the appeal, marking the second time in less than a year that the Supreme Court agreed to weigh in on fair use. This follows a 27-year hiatus since the Court’s seminal Campbell v. Acuff-Rose decision in 1994, in which it unanimously held that a parody of the Roy Orbison song Pretty Woman by 2 Live Crew was fair use. In April 2021, 10 days after the Warhol decision, the Supreme Court ruled in Google v. Oracle America that Google’s use of a portion of the Oracle Java computer program in Google’s Android operating system constituted fair use.

The Supreme Court’s further review of fair use is welcome news. Since the Campbell decision, in which the Court clarified that the four-factor test set forth in the Copyright Act to determine fair use needed to be applied in toto, federal courts have wandered all over in deciding whether a particular work makes fair use of another’s work. This is not surprising given the complexity of applying the four-factor test to a myriad of new and different works. However, this wide range of interpretations has been frustrating to artists and practitioners, alike, who are unable to discern with any degree of certainty when a work of art has availed itself of the fair use doctrine and when it has not.

A bit of background: The owner of a copyright such as a photograph, a sound recording, or even a software program, has five exclusive rights to the work: reproduction; distribution; performance; display; and derivative works. However, because the Copyright Clause of the U.S. Constitution expressly states that these exclusive rights are intended “[to] promote the Progress of Science and the Useful Arts …”, the courts have implied a right to fair use of a copyrighted work even before the Copyright Act enshrined the concept in Section 106. Section 106 of the statute sets forth a four-part test for determining whether a work makes fair use of another work: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. In Campbell, the Supreme Court said that all of these factors must be considered, even if some may be more important than others in a particular case.

The Supreme Court also emphasized, in connection with the first factor, that the “transformative” nature of the new work in relation to the old could be determinative. Justice Souter wrote that “the enquiry focuses on whether the new work merely supersedes the objects of the original creation, or whether, and to what extent, it is ‘transformative,’ altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message.” Moreover, “[t]he more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”

Most subsequent courts presented with a fair use defense have focused on the transformative nature of the new work, but with widely divergent results. In many cases, the courts have assumed the role of art critic (as the Second Circuit did in the Richard Prince and Warhol decisions, despite protestations to the contrary), viewing each allegedly infringing work side-by-side and determining, on their own and without the benefit of extrinsic evidence or expert testimony, whether or not the new work transformed the original work.

Needless to say, most judges (indeed most lay persons, including yours truly) make poor art critics, and as a result, the decisions have created a hodgepodge of rulings that depend primarily on the reviewing court’s subjective review of works of art, even though the courts profess to be applying an “objective” standard. As with the legal definition of pornography, these judges may not be able to define transformation, but they sure know it when they see it. This is an unfortunate state of affairs and certainly not what the Framers intended when they included the Copyright Clause to “promote the Progress of Science and the Useful Arts.”

In Oracle, the Supreme Court again focused on the transformative nature of Google’s use of the Java program to find fair use. Using Oracle’s programming language as a building block for the Android platform constituted a legitimate fair use because Google “transformed” the Java program by implementing Java’s user interface to create new products and used “only what was needed to allow users to put their accrued talents to work in a new and transformative program.” Thus, in the only two cases in which the Supreme Court has addressed fair use in the last 27 years, the Court in each case overwhelmingly found that fair use applied.

One hopes that in reviewing Warhol, the Court will further clarify the confusing jurisprudence that has sprung up since Campbell. If it does, one (the original artist) or the other (the transforming artist) is likely to be disappointed, but at least artists will have greater clarity as to what does and does not constitute fair use in today’s rapidly evolving artistic environment.

Jose Sariego is a corporate partner at Bilzin Sumberg with over 30 years of experience negotiating and closing domestic and international mergers and acquisitions, investments, joint ventures, divestitures, and other transactions.