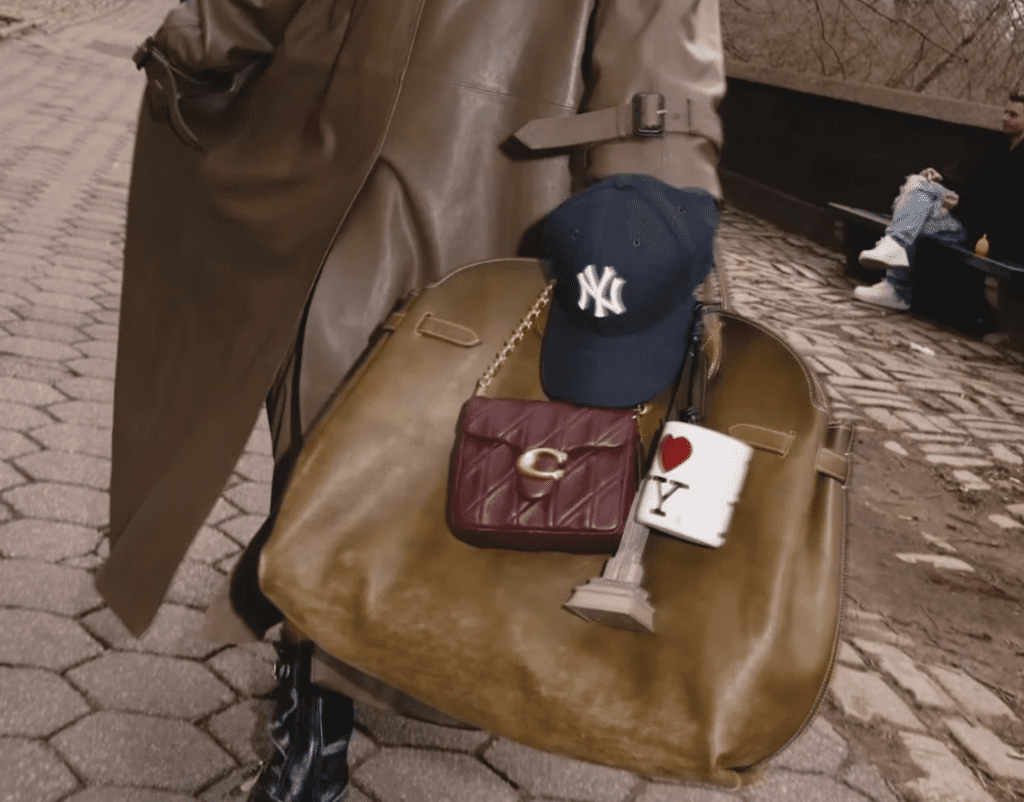

The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) has set its sights on blocking the $8.5 billion merger between fashion giants Tapestry and Capri, which would bring the Michael Kors, Versace, Jimmy Choo, Coach, Kate Spade, and Stuart Weitzman brands under the same ownership umbrella. The proposed merger between the two fashion groups has faced scrutiny from the FTC, which has argued that the headline-making deal will lessen competition in the “accessible luxury” market. While the regulator argues the proposed transaction would impact competition in the luxury handbag market and harm consumers in the process, experts see potential impacts for future mergers and the retail industry as a whole.

A Straightforward Case?

From an antitrust perspective, the case is relatively straightforward, according to Wyatt Fore, a partner at Shinder Cantor Lerner LLP. While many recent antitrust cases under Lina Khan’s tenure as FTC chair are exploring new theories, the Tapestry, Capri matter relies on well-established legal principles, namely, head-to-head price competition and market concentration. “The merger is presumably illegal because of that increase in concentration,” he explained.

However, despite its seemingly simple foundation, the case has drawn attention due to its implications for defining product markets within the luxury goods space. The FTC is focusing on a “three-tier market” structure, categorizing brands into mass market, accessible luxury, and high-end luxury segments, Fore said, noting that this is relatively uncommon in antitrust cases. “If there’s anything about this case that makes it not a totally straightforward theory, it is that one,” he said.

As such, market definition has become one of the most hotly debated aspects of the case, with both sides presenting starkly different perspectives, which illustrates how challenging it can be to draw boundaries between product markets. For example, in the case at hand, Capri and Tapestry argue that the boundaries between luxury and accessible luxury are blurred due to modern consumers’ buying patterns. In particular, the two fashion groups claim that consumers often move between market tiers, making it difficult to define distinct markets.

Prachi Ajmera, counsel at Michelman and Robinson LLP, acknowledged that defining markets in fashion is inherently challenging. “It depends who you’re asking,” she said about whether or not the FTC’s view is too narrow (as Tapestry, Capri, and market experts, alike, have argued). She noted that the fluid nature of consumer behavior in fashion, where consumers often cross-shop between high-end and more accessible brands, raises questions about how to regulate a market that resists traditional economic definitions.

Fore emphasized that the FTC only needs to show that its proposed market definition is valid, not that it is the only possible one: “All the FTC has to do is meet its burden of showing that this market is applicable, not that other markets are not also applicable.” As for Tapestry and Capri’s likelihood of success here, Fore said that their internal documents may undermine their argument. “The defendants’ own documents seem to indicate that they conceive of [affordable luxury] as a market,” which could complicate their arguments against it.

> It is worth noting that the case raises questions about the kinds of evidence that courts should prioritize in antitrust cases. Fore says that there is often a split between those who believe internal communications are highly probative and those who view them as less reliable. “Some people think that internal documents are the most probative documents in a case, but some people think that economic evidence is the most probative because it’s objective,” he stated.

In this case, the FTC is heavily relying on internal documents to support its market definition. “The merging parties consider this to be a critical way of analyzing the market, and that because they see this as a way of evaluating the market, the FTC thinks that this is very persuasive,” he said. If the court ultimately bases its decision on the parties’ internal communications as opposed to its public facing messaging, it could have broader implications for how future antitrust cases are litigated in terms of dependence on this kind of evidence.

A Signal to the Industry

The outcome of the case could send a message to the fashion industry and beyond. The case will serve as “a signal” about how the FTC’s pro-competition directive “extends to the entire U.S. economy, and they are going to be enforcing the law widely,” he said, referring to the agency’s mission to protect consumers and ensure a competitive marketplace by enforcing laws related to antitrust and unfair business practices. This could have a chilling effect on future mergers and acquisitions in the fashion sector, particularly among luxury brands, which is significant in light of the fashion industry’s existing move towards consolidation by major conglomerates like LVMH.

If the FTC loses this case, it could accelerate the already-prevalent trend towards consolidation in the fashion/luxury market as a whole. However, if the FTC prevails, it could make it more difficult for brands to consolidate in the future. The case could also influence how brands structure future deals, particularly in terms of how they define and present market competition. Fore suggested that a loss for the FTC could give fashion brands more “leash” for future acquisitions, whereas a win might lead to increased scrutiny over how market definitions are drawn. And whether or not the agency wins or loses, it “will probably inform how they bring future cases,” Fore predicted.

At the same time, even if the FTC does prevail, that is unlikely to prevent future mergers, per Ajmera, who said that such an outcome is unlikely to deter other brands from pursuing similar deals in the future. “There are a lot of benefits for brands to join under one conglomerate,” she said, citing the potential for the consolidation of supply chains and the ability to operate on a more efficient scale.

Ultimately, the case may seem focused on the niche world of luxury fashion, but Fore emphasized that its implications extend beyond handbags and high-end brands. He said that the FTC’s broader strategy involves enforcing antitrust laws across all industries, signaling that no sector is exempt from scrutiny. “Their mandate includes protecting all consumers throughout the United States in whatever market law is being violated.”

The case is Federal Trade Commission v. Tapestry, Inc., 1:24-cv-03109 (SDNY).