A quiet settlement is not in the cards for Valentino and Mario Valentino. In a joint report filed with the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California earlier this month, counsel for both brands revealed that the routine settlement conference that the parties recently engaged in has not resulted in an out-of-court resolution, and that they “do not believe that a second session would be productive” at this point, noting that “a second session may be productive after completion of summary judgment briefing.”

The like-named parties have been going back-and-forth since Valentino S.p.A. (“Valentino”) filed suit against Mario Valentino in July 2019, accusing the unaffiliated brand of breaching the co-existence agreement they both signed off on more than 40 years ago in furtherance of an attempt to avoid legal complications stemming from their nearly-identical monikers. Valentino asserted in its complaint that “because of their similar names and overlapping goods,” the two companies “experienced issues of consumer confusion” almost from the outset, prompting them to enter into a co-existence agreement in 1979.

As it turns out, while Valentino – the Italian fashion brand founded by designer Valentino Garavani in late 1959 – may be the more well-known of the two, thanks to its breathtaking couture, lengthy roster of mega-celebrity fans, and stable of revenue-generating accessories, Mario Valentino was actually the first-mover. In fact, when 28-year old Garavani – fresh from working for Jean Dessès and Guy Larochem and attending fashion school in Paris – first opened up shop on Via Condotti in Rome with a business that focused exclusively on fashion, or what has been likened in retrospect to the Italian equivalent to French couture, the unrelated Mario Valentino was already in business in Italy. Mario had been offering up footwear under the Mario Valentino name beginning in 1952, and would swiftly expand into other leather goods, as well.

(Now best known for familiar-looking handbags and footwear that often populate the shelves of Saks Off Fifth, T.J, Maxx and Marshalls, in its heyday, Mario Valentino counted Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Elizabeth Taylor, Catherine Deneuve, and a long list of Italian actresses, among others, as fans, and boasted collaborations “with designers of the calibre of Karl Lagerfeld, Giorgio Armani, Gianni Versace,” as well as famed photographer Helmut Newton, who shot ad campaigns for the brand).

Faced with mounting consumer confusion and a respective “desire to avoid public confusion and conflict, present or future, in any part of the world,” Valentino and Mario Valentino entered into a legally-binding agreement that laid out exactly how the respective fashion brands would use their various Valentino marks for decades to come. According to that agreement, dated May 11, 1979, Mario Valentino is permitted to “use and register … Mario Valentino, M. Valentino, Valentino or the letters MV or V exclusively on the outside [of] … and on the packaging [of] all goods made of leather … together with the Mario Valentino [name] on the inside.” The agreement also limits its use: Mario Valentino is “not permitted to use the ‘V’ and ‘Valentino’ marks together” on those same types of goods.

Put simply, Mario Valentino can use the “Valentino” name on leather goods, such as handbags, assuming it includes the full “Mario Valentino” name on the inside of the product. No small coup in hindsight. However, it made sense at the time, as Valentino was not yet in the big business of leather goods, the very things that currently drive no small portion of its annual revenue.

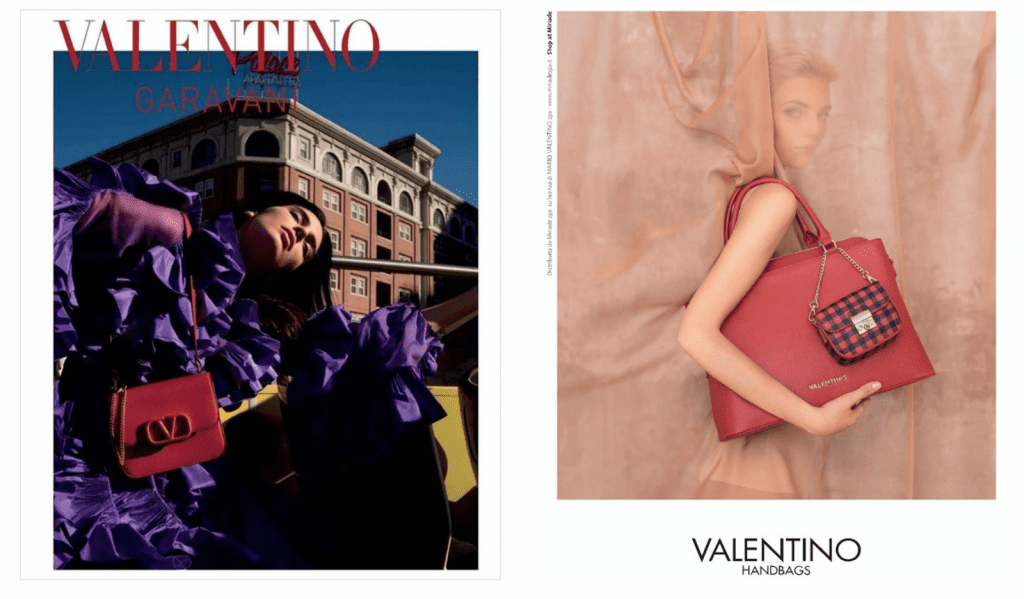

In terms of its rights in the agreement, Valentino enjoys the ability to use the Valentino name – with or without the brand’s “V” logo – on all goods … except for footwear and various types of leather goods, such as handbags. For those latter goods, Valentino may use “Valentino Garavani” and/or “Valentino Couture” – but not merely “Valentino” on its own.

With that agreement in mind, Valentino alleged in its strongly-worded complaint last year that Mario Valentino and its American licensee Yarch Capital are “actively engaging in a campaign to trade off on [its] goodwill in the U.S. handbag market” by making and marketing handbags with packaging “that prominently identifies the bags as coming from ‘Valentino,’” and simultaneously making use of Valentino’s “V” logo, which is explicitly prohibited by the globally-reaching co-existence agreement. At the very same time, Valentino argues that the defendants are “downplaying or omitting entirely” the fact that their bags are Mario Valentino bags, and not associated with the Valentino brand, all while quietly – but “significantly” – raising the prices of their bags to be “closer to the prices associated with Valentino bags,” and “have further enhanced the likelihood of confusion by copying the designs of Valentino’s handbags, including designs covered by valid design patents.”

A Fight for the Right

To date, the lawsuit has centered largely on allegations about the goods being offered up by Mario Valentino and the company’s – and its licensee’s – marketing of them, as well as jurisdictional issues, as there are cases currently underway in court in the U.S. and in Milan. But beyond the likelihood of confusion assertions, design patent infringement claims (over Mario Valentino’s own studded offering), and rival arguments about the appropriate forum for the case to be heard, the matter is arguably about much more than the co-existence agreement and whether Mario Valentino is breaching it by way of its lookalike products and “Valentino”-centric marketing campaigns.

The stakes are actually quite a bit higher than that, and in fact, the more critical fight here is likely about the right to use the Valentino name on leather goods, which – in 2020 – serve as the bulk of both brands’ businesses even if Valentino’s roots are in couture.

One of the glaring issues at play is that Valentino – while the undoubtedly bigger, mightier brand and the undisputed fashion force in the squabble at hand – lacks the legal ability to use its “Valentino” name on some of the most important products in its lineup, the very goods that it sells the most of. That is why its expensive leather handbags and hot-selling Rockstud-adorned footwear are branded as Valentino Garavani.

Branding-wise, this does not appear to have been a deal breaker. Valentino simply includes the words “Garavani” and/or “Couture” on its leather goods and footwear in order to remain within the confines of the co-existence agreement. It can similarly stay in-bounds and use its famed “V” logo, which it does … on no small number of handbags, shoes, belts, etc. In other words, the agreement has not prevented Valentino from using its name to such a striking extent that it cannot engage in the logo-centric activities of modern luxury manufacturing. (“VLTN” also appears to be fair game based both in the terms of the agreement and the sizable offering of bags bearing that mark being sold by Valentino).

Where the brand’s inability to simply use the “Valentino” name on its own (i.e., without “Garavani” or “Couture”) in connection with certain categories of goods seems like it would have the biggest impact is on the value of the brand, itself. This is particularly relevant given that much of the value of a fashion company – or any consumer-facing company for that matter – is intrinsically tied to its branding and the intellectual property rights that come with that.

Valentino has no shortage of trademark rights and registrations (and trade dress rights, as it is currently arguing in a number of different filings with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office) in its name – from Valentino for use on eyewear, and Valentino Garavani on handbags, footwear, and clothing to the V logo on nearly any category of goods – that another party would take ownership of if it acquired the Valentino brand. However, it is difficult not to suspect that an acquiring party may take issue with the fact that one core element is missing from the brand’s portfolio: the ability to use Valentino for use of leather goods and footwear.

Interestingly, that has not necessarily proven problematic for Valentino to date. After all, Valentino’s former owner private equity firm Permira sold the Valentino Fashion Group – which included “100 percent of Valentino SpA and the M Missoni license business,” as WWD reported in 2012 – to Qatari investment group to Mayhoola for Investments in July 2012 for a reported 700 million euros ($856 million). The deal made headlines for the sheer size of it.

The acquisition was deemed “a win-win situation for Valentino,” according to Armando Branchini, deputy chairman of Milan consultancy InterCorporate. Meanwhile, Reuters revealed that the 700 million euro figure paid by Mayhoola was 31.5 times the 2011 EBITDA for Valentino, thereby putting the selling price “well above LVMH’s purchase of jewelry maker Bulgari [in 2011] at 28.2 times its EBITDA,” one of the more recent and relevant transactions at the time. It would also prove to be quite a bigger than the EBITDA-times-14 deal that Mayhoola entered into in June 2016 when it acquired Balmain; the price tag on that acquisition was 460 million euros ($522 million).

As for whether Mayhoola would have had to pony up more cash if Valentino had global trademark rights in its portfolio for the use of the Valentino on leather goods and footwear, it seems like it would have, at least in theory. However, on paper, the deal did not suffer, with the price paid by Mayhoola amounting to what Reuters characterized as “a huge premium against current average valuations for European luxury brands which stand at 10-11 times 2012 forecast EBITDA.”

*The case is Valentino S.p.A., v. Mario Valentino S.p.A.; Yarch Capital, LLC, 2:19-cv-6306 (C.D.Cal.).