Facebook, Inc. is changing its name to Meta. That was the news on Thursday after months of speculation about a potential change in name for the troubled tech group, and amid its efforts to fend off what has been called “one its worst crises yet,” and to “pivot to its ambitions” to the metaverse. A name change does not necessarily change much if the workings of the company formerly known as Facebook (and which may continue to be referred to as such by consumers in the same way as Google has found it difficult to get laymen to put its 2015 rebrand to Alphabet into practice) do not change along with it.

After all, “A great name does not a great company make,” according to veteran linguist Anthony Shore, whose firm Operative Words has worked with brands like Adobe, Fitbit, Virgin, Neiman Marcus, and FedEx, among others. Nonetheless, Shore noted on Thursday that Facebook, Inc.’s name change – one that impacts the overarching parent company as distinct from the individual social media brand – “makes sense from a brand architecture standpoint” in the same that that Adobe should not be named Photoshop.”

Facebook is, of course, not the only one to change its name as of late, and in fact, companies commonly tweak their monikers for an array of reasons – from an attempt to reposition a beleaguered brand to a bid to reflect an expansion beyond a company’s initial offerings. And still yet, in some cases, as Venable LLP’s Andrew Price and Meaghan Kent noted, a rebranding exercise that is aimed at maximizing brand value, including in challenging times across industries, “may have to look beyond just changing [a company’s] own name or logo.” In such instances, “the rebrand will not only have to portray how the particular company has changed or grown but may also have to articulate how its profession or field, as a whole, has grown or matured. (Facebook’s name change is likely a bit of each of these.)

Fosun Fashion Group’s recent rebrand to Lanvin Group comes to mind. Fosun revealed this month that behind its decision to rebrand the fashion holding company is “a strong belief that the spirit and ethos of Jeanne Lanvin.” Realistically, Lanvin Group likely just sounds better, and is more widely known as having a reputation in the luxury segment, which is relevant as the group says that it is entering “the next phase of its global development.”

The Fosun name change comes almost three years after Michael Kors, the group, became Capri Holdings after scooping up Versace, and creating what CEO John Idol called “one of the leading global fashion luxury groups in the world.” And a year before that, Coach, Inc. rebranded as Tapestry following its acquisition of Stuart Weitzman and Kate Spade. In both cases, the moves were (at least partially) aimed at broadening the image of the two entities, which started as single brands, to multi-brand entities, and signifying a change in strategy.

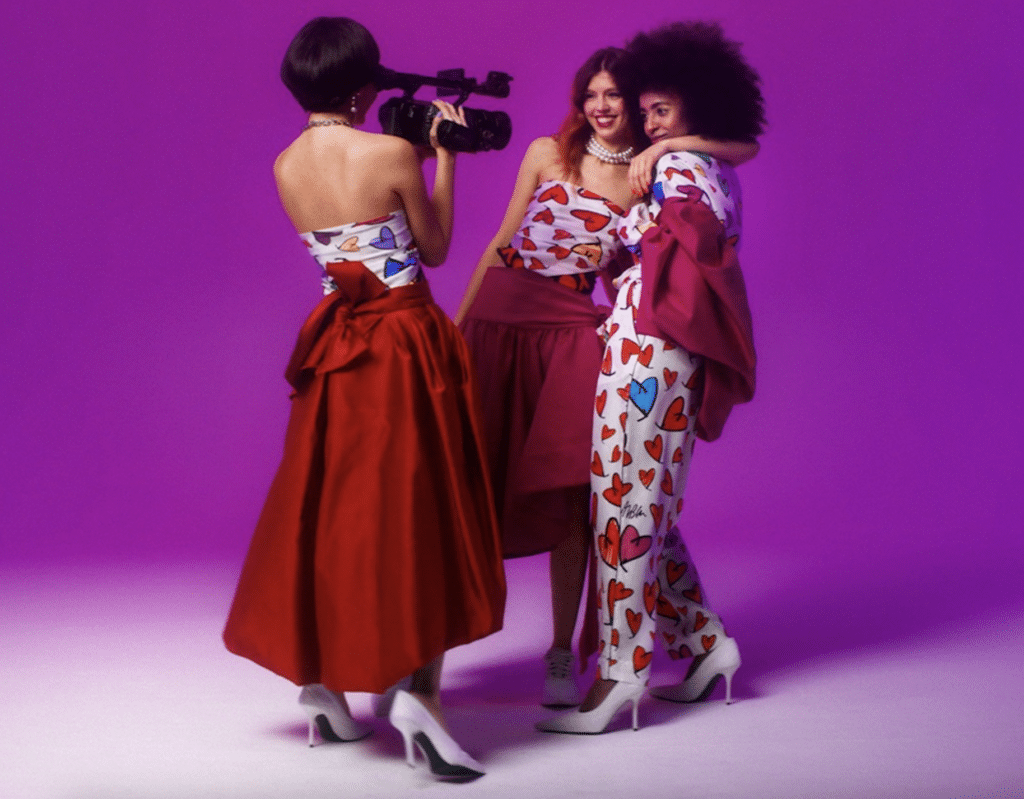

Just as will be the case of Facebook-turned-Meta, the rebrands by Coach and Kors required more than merely a swap in stock market ticker symbols, and both have come with broader change within the groups, including an enduring push upmarket. For Capri, that looks like a “considerable” raise in prices and a continued movement away from aggressive discounting. Diving the Tapestry move is its marquee Coach brand, which has been busy increasing marketing spend and enlisting mega-stars, such as J. Lo., to cement its more upscale positioning and reach younger consumers by convincing them that the new Coach is “not necessarily your mother’s Coach.” (My words, not Coach’s.) From a sales perspective, the revamp is working for Tapestry; for Q4 2021, Tapestry reported 60 percent year over year growth in Mainland China and triple-digit full-year global digital gains.

For Facebook – err Meta, it almost certainly will not be as simple as boosting ad spend and enlisting enticing brand ambassadors. However, at least some are optimistic that its evolution – both in name and in practice – could prove fruitful, assuming that it can convince consumers to join it in the metaverse.

A final takeaway worth considering for companies that are engaging in – or toying with the idea of – a rebrand is what happens to pre-rebrand assets. Meta, for one, has significant reason to maintain its use of and rights in the Facebook name thanks to its individual social media brand. But what about other companies?

Price and Kent assert that in the wake of a rebrand, “it may be worth keeping old logos and other legacy marks visible on websites and other branding materials to help customers recognize the [new] brand and understand the purpose behind the rebrand.” Beyond aiding consumers amid a branding transition, they claim that “keeping these legacy marks alive also serves to protect them from misuse and helps to bridge the gap between the old brand and the new.” From a purely trademark perspective, if any of the formerly-used names, logos, etc. are still in use, it “can also be advisable to keep certain strategic registrations alive for legacy brands for a period in order to preserve ‘residual goodwill.’”

UPDATED (Oct. 30, 2021): Facebook, Inc. filed an intent-to-use trademark application for registration for Meta on October 28 in classes 9, 28, 35, 38, 41, 42, and 45. This is a tiny excerpt of the very lengthy list of classes of goods/services, which consists of more than 16,500 words …