After our 2023 Barbie Pink summer, we are having a BRAT Green moment. Described by the pop singer Charli XCX as slimy, really unfriendly and uncool, and even offensive, off-trend and wrong, the cover of the artist’s latest album is meant to epitomize the idea of brat. In other words, having “a party girl lifestyle with a polished edge” and also being “honest, blunt, and a little bit volatile.” The viral Apple dance, the swatches of BRAT green held up by Charli XCX’s fans during her concerts, and the BRAT wall indicate the color’s embrace by consumers of Charli XCX’s music. But this particular shade of green has also been embraced beyond consumers of Charli XCX’s music.

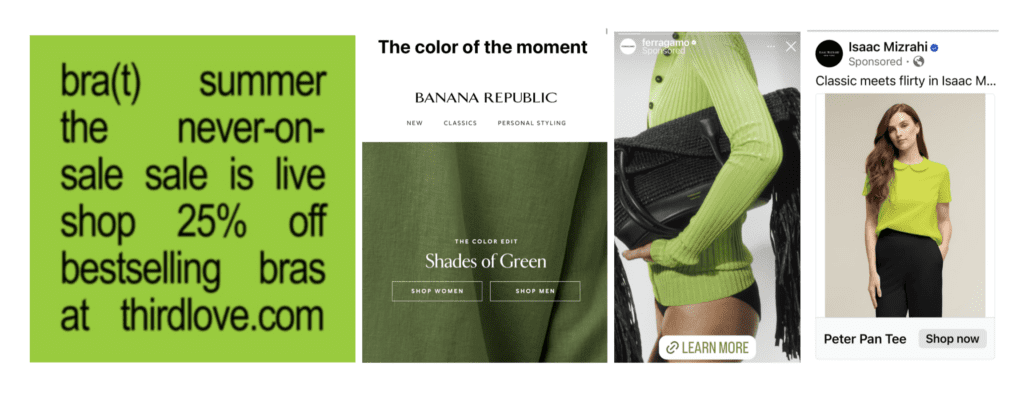

Fashion brands, for example, are citing the shade of green implicitly and expressly in their own promotional campaigns. Using BRAT green, or even just referencing it, is one way that fashion brands are riding a pop culture moment to compete for consumers on the market and sell their products.

As BRAT green has hit the zeitgeist, commentators have noted that it’s far from a color that is foreign to the fashion industry. In what we might call a fashion feedback loop where present colors are inspired by past colors and past colors become relevant for the present, commentators have seen the antecedents of BRAT green in Miuccia Prada’s 1996 Prada collection, the Spice Girls’ 2 Become 1 album cover and music video, and even in a 1968 VOGUE cover story promoting “Beauty and the Little Green Dress” for that 1960s summer. The private regulator of color most called on by fashion brands, Pantone, has even been identified as starting a cyclical craze for green with its christening of greenery as the color of 2017.

As BoF observed even when looking at 2024 fashion shown before Charli XCX’s album dropped, “a brat-style green was on Prada and Gucci’s menswear runways last month, and has been on the rise for a few seasons now, according to trend analytics firm WGSN.”

Far from shying away from this feedback loop, Charli XCX has leaned into the color’s accessibility through her album’s marketing campaign. Brands can use the Brat generator to create their own promotional images in BRAT green. As Vogue Business reported, “Brat has generated $22.5 million in media impact value, according to Launchmetrics.” Brands are participating in the trend to increase their own sales. But this accessibility also raises a legal question. Why are today’s originators of colors, like Charli XCX, facilitating easy access to the colors they have invested a great deal of time and money to develop? Why can competing brands all reference the same BRAT green?

The easy answer to this question is that, despite its totalizing presence this summer, BRAT green has likely not yet acquired the function that trademark law cares about most: signaling source or the origin of the goods on which it is placed. As TFL has previously outlined in its Primer on Color Trademarks, colors in the fashion industry that are applied to specific products can be owned by fashion brands as trademarks. Colors, in other words, can act as indicators of source: telling consumers who made or stands behind a product offered for sale. But colors’ ability to indicate source and act as trademarks can only happen after a period of time. This acquisition of the ability to indicate source, or acquiring distinctiveness, is known as secondary meaning. Colors are considered trademarks under the law only after consumers see a color on a specific product and think of who made the product. This association subsumes other, more primary, messages that a color might convey.

To take the exemplary fashion example, consumers need to see red on the sole of a shoe and think that Louboutin made the shoe, not just that red is a sexy color or a color that’s prevalent in a particular design aesthetic like “Chinese-themed fashions” (to quote YSL’s arguments that it had fairly used Louboutin’s red).

Felicia Caponigri is a Visiting Scholar at Chicago-Kent College of Law and the Founder of Fashion by Felicia, LLC. An attorney by training and an academic by calling, her article proposing a doctrine of cultural functionality in trademark law is forthcoming in 2025 in the American University Law Review’s volume 74.

This is a short excerpt from a Deep Dive that was published exclusively for TFL Pro+ subscribers. Inquire today about how to sign up for a Professional subscription and gain access to all of our exclusive content.