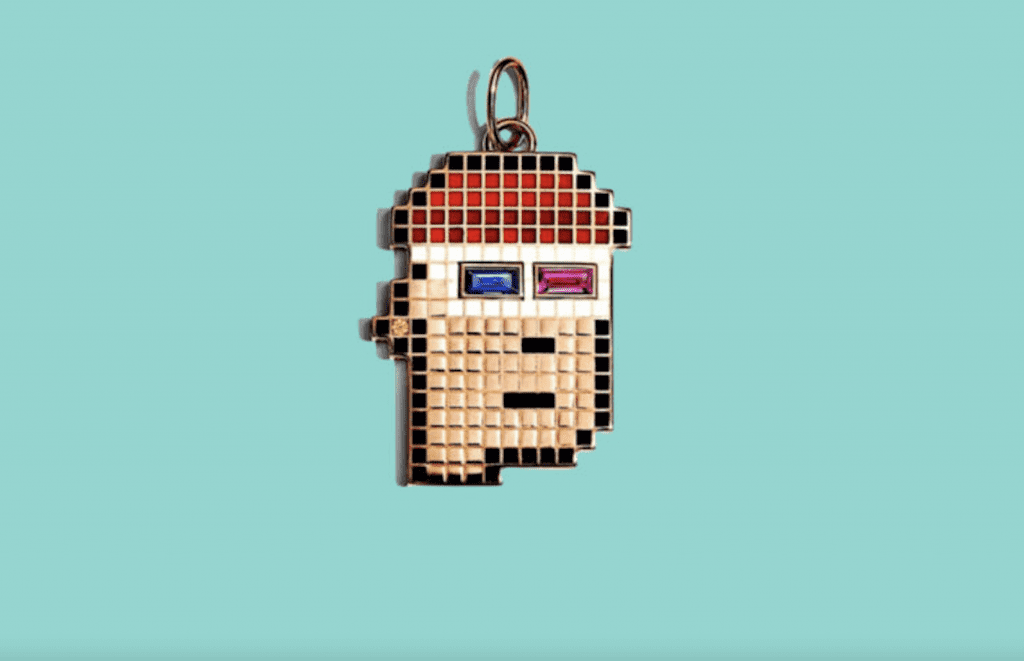

Tiffany & Co swiftly pre-sold a collection of 250 “digital passes” to holders of non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) from the popular CryptoPunks collection on Friday. Entitled NFTiffs, the passes can be redeemed by current CryptoPunks holders (and current CryptoPunks holders, alone) for the creation of a custom designed pendant – made of gold and gemstones – that resembles their individual CryptoPunks, the LVMH-owned jewelry company revealed. In addition to the tangible jewelry items, which are expected to be available for the pass holders beginning in early 2023 (assuming these individual still own their CryptoPunks), NFTiff buyers also get a “standalone custom 1 of 1 NFT on the Ethereum blockchain” that is tied to digital artwork that resembles the final jewelry design.

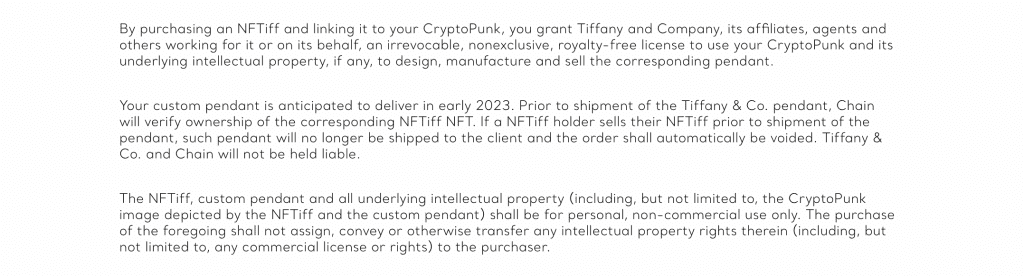

CryptoPunks holders were quick to snap up Tiffany & Co.’s NFTiffs, which were initially offered up – in conjunction with blockchain-based technology company Chain – for 30 ETH (the equivalent of $50,000). But in the wake of the launch, the venture was met with some pushback, primarily on social media, stemming from the terms of the offering. In particular, most attention centered on a provision in the NFTiff Terms and Conditions that previously stated, “By purchasing an NFTiff and linking it to your CryptoPunk, you grant Tiffany and Company, its affiliates, agents and others working for it or on its behalf, an irrevocable, nonexclusive, royalty-free license to use your CryptoPunk and its underlying intellectual property, if any, to design, manufacture and sell the corresponding pendant, including any and other Intellectual Property Rights.” (Emphasis courtesy of TFL.)

For the most part, the provision makes sense in that it gives Tiffany the ability to make use of the intellectual property in the various CryptoPunks to manufacture and offer up pendants – and digital imagery of the pendants – without engaging in copyright infringement and/or trademark infringement, with the latter coming into play given Tiffany’s use of the “CryptoPunks” mark on and/or in connection with the NFTiffs and pendants. It is worth noting that Tiffany & Co. can get such a license from the CryptoPunk NFT holders, themselves, and thus, does not need authorization from Yuga Labs because when Yuga acquired the CryptoPunks collection, including the “brand and logo,” earlier this year from Larva Labs, it announced that it would grant “IP, commercial, and exclusive licensing rights to [the] individual [CryptoPunks] NFT holders.”

(While the exact terms of the impending license that CryptoPunks is offering to its NFT holders are not clear, the Tiffany & Co.-crafted pendants and corresponding NFTs “perfectly illustrate the license that’s coming out,” CryptoPunks’ brand lead Noah Davis told CNN in the wake of the NFTiff launch, a nod to the “certain rights” that CryptoPunk NFT holders have “with regards to what you can do with your CryptoPunk, what kind of IP you can build around it.” In this instance, Davis says that the owners of Cryptopunks are “essentially commissioning Tiffany’s to create new IP out of their CryptoPunk, and that new IP is a pendant.” (Is that really “new IP” – or it is simply a new application of existing copyrights/trademarks?))

“A reasonable interpretation” of this section of the NFTiff terms “is that the purchaser is granting Tiffany’s a limited royalty-free license to use the purchaser’s CryptoPunk and its underlying intellectual property, solely for designing, manufacturing and selling the corresponding pendant,” attorney Dean Wolf stated on Twitter. However, the inclusion of the terms “any and other Intellectual Property Rights” related to the CryptoPunks at the end of the NFTiff license provision raised eyebrows (and in some cases, prompted claims that Tiffany & Co. was looking to suck rights from CryptoPunks holders, which seems unlikely).

Reflecting on the “any and other Intellectual Property Rights” clause, Wolf noted that “a broader interpretation” could be that “the purchaser is granting Tiffany’s a royalty-free license to: 1) use the purchaser’s CryptoPunk and its underlying intellectual property (in any capacity); and (2) to design, manufacture and sell the corresponding pendant.”

The NFTiff terms were updated over the weekend to remove the “any and other Intellectual Property Rights” language, thereby, clarifying questions and/or concerns about whether the jewelry company was angling to amass broader rights in various CryptoPunks. (It is not.)

As for what can be taken away from the NFTiff terms debacle, among other things, it seems to serve as a reminder of the apparent clash that can arise between the web3 approach to ownership, namely, a push to distribute ownership more evenly between companies and individuals, and the approach that companies traditionally take – and the very-standard legal language that they use – when it comes to things like licensing. (Tiffany is, of course, not alone in utilizing such language. Instagram, for example, enjoys a “a non-exclusive, royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license” that gives it the ability to make use of users’ content.)

It is difficult (as of now) to see big-name luxury companies, like Tiffany & Co., drastically changing their approach to drafting, including and/or not including well-established terms to better fit into the web3 mentality. That does not mean, however, that there is not something of a middle ground. University of Kentucky Law professor Brian Frye claims that “Tiffany’s attorneys should have made the agreement clearer and easier to understand,” for example, given that “the customers for this project” (and maybe NFT holders generally?) “are antsy about ‘IP’ and the lawyers should have anticipated these concerns.”

This sheds light on a larger issue that has also been coming up in a number of NFT and metaverse-centric lawsuits: As companies venture into this web3 (either via projects of their own or lawsuits that they are initiating), they need to collaborate closely with lawyers that not only understand the law in this area but that appreciate the ethos of the web3 space. This is true both from a transactional perspective (anticipating the response from CryptoPunks holders could have potentially helped Tiffany & Co. to avoid the backlash over the NFTiff terms), and from a litigation point of view given that in more than one case (Hermès v. Rothschild and Nike v. StockX come to mind), brands that have landed on the receiving end of web3-centric infringement lawsuits are arguing that the suits are misguided and that the plaintiffs simply do not understand what NFTs are and how they actually work.

Potential missteps could prove costly from a litigation POV, but beyond that, claims, such as those from Mason Rothschild’s counsel that Hermès is looking to “suppress Rothschild’s art and to restrain his protected speech,” or those from StockX, which has argued that Nike’s lawsuit is little more than an “anticompetitive” attempt to “stifle the secondary market [and] hurt consumers,” could also cost brands by way of unfavorable PR.

Ultimately, this appears to be the latest example of why “brands and trademark practitioners, alike, [need] to wrap their heads around what is taking place” in web3, as Frye previously told TFL, and that they would likely benefit from enlisting counsel that is well-versed in the nuances of this arena in order to successfully engage in it – and/or to successfully wage and/or defend against lawsuits that involve it. And this is especially important in light of one of the biggest takeaways from the successful NFTiff launch: It demonstrates the desire of consumers (and increasingly, luxury brands) to become part of this space and their willingness spend sizable sums to do so.