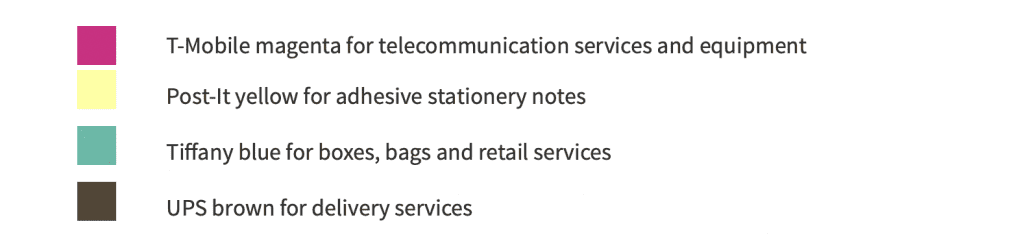

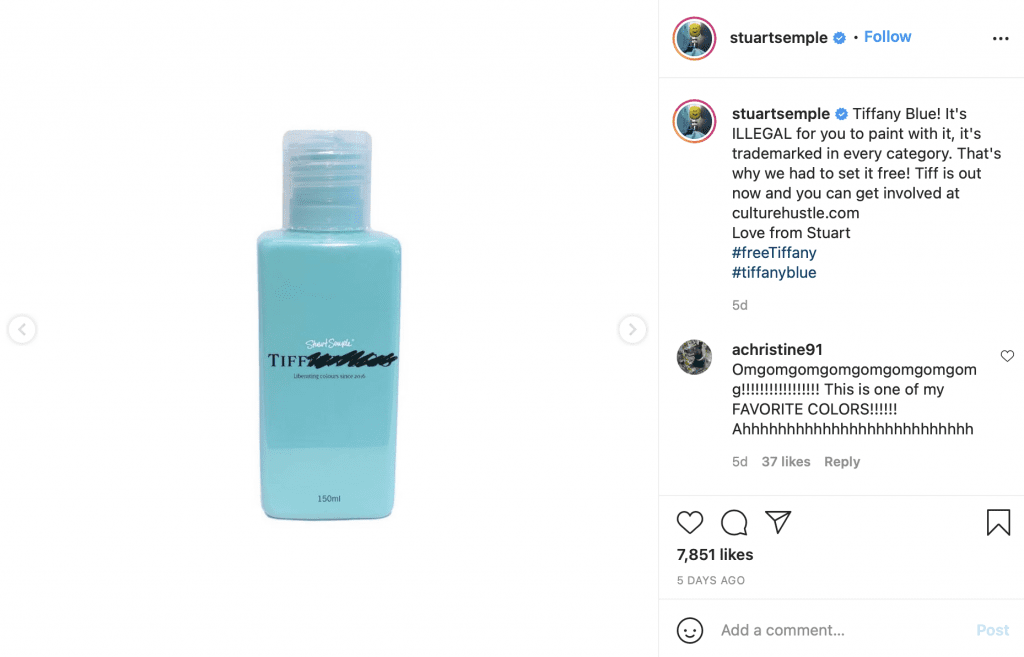

Stuart Semple is looking to #FreeTiffany. In order to “liberate” Tiffany & Co.’s signature hue, the British artist created a “super flat matte high-grade shade” acrylic paint that mimics the stalwart New York-based jewelry brand’s robin’s-egg blue, and recently offered 150 ml tubes of it for sale on his e-commerce site for $28, all of which have since sold out. The aim of the project? To make “this once unattainable color” available to “all artists to use in their creations.” Speaking to his desire to take on Tiffany’s blue, Semple states on his website that “the iconic Tiffany Blue was created by Charles Tiffany and John Young in 1837, and is a trademarked color that needs a license to use it.” While “many corporations have trademarked colors, like T-Mobile’s Magenta or Coca Cola’s Red,” what Semple says “makes Tiffany Blue different is that its trademark is across all uses since 1998, and they have even hidden the Pantone code.”

Semple’s Tiffany-specific venture – and in particular, the language that he uses to describe the project – is thought-provoking, and provides an opportunity to dive into the bid by brands to monopolize colors for the purpose of their specific offerings and oftentimes, their marketing. It is important to note, of course, that such language largely overstates the rights that Tiffany & Co. actually maintains in the specific blue hue (and the rights that brands can reasonably expect to have in a color mark).

While Semple asserts that “the iconic Tiffany Blue has been held tight in the Tiffany & Co. grasp” because the LVMH-owned jewelry company holds trademark rights “across all uses since 1998,” that is not necessarily true based both on how trademark rights are amassed in the U.S. and how Tiffany & Co. is actually using the blue hue. “In the U.S., it is possible under certain circumstances to register a color as a trademark,” trademark attorney and former U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) trademark examiner Dana Dickson wrote in a recent post. After all, in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., a landmark case that centered on the protect ability of the green-gold color of Qualitex’s dry cleaning press pads, the Supreme Court explicitly stated that a color can be registered as a trademark, as long as it identifies a single source for the products/services at issue.

In short: an individual color can be legally protected as a mark, assuming that the use of the color is non-functional and that the brand at issue can establish that consumers have come to associate the color with a single source rather than merely with the products or services themselves.

Not exactly an effortless endeavor, Cowan, Liebowitz & Latman attorney Dasha Chestukhin has noted that “acquired distinctiveness (also called ‘secondary meaning’) can be extremely difficult to establish” when it comes to colors, since “generally color takes some time to be recognized as a source indicator. However, establishing the requisite level of distinctiveness is not impossible. Christian Louboutin, for instance, maintains valuable trademark rights in Pantone 18-1663TP for use on the soles of contrasting-colored shoes. Cartier enjoys rights in a different shade of red for use on certain product packaging, namely, tied to its sale of jewelry; Hermès has trademark rights in its specific “shade of the color orange” for use on packaging in connection with the sale of ready-to-wear, leather goods, and other products; and even Glossier has claimed rights in some specific uses of millennial pink … just to name a few examples.

Yet, even if a brand can amass such rights and corresponding trademark registrations, that is “not a blanket permission to use that color on any object in any way and to prevent anyone else from using that color in any way,” Dickson states, further asserting that the USPTO has been clear that “color marks are marks that consist solely of one or more colors used on particular objects.” Or – in other words, “The registration is not for the color in the abstract (used on anything and everything to indicate the source of all imaginable goods and services),” and instead, such protections only extend to: “(1) use of the color on a particular object, [and] (2) for the purpose of identifying the source of only the goods/services indicated in the [party’s trademark] application” and/or registration.

A quick overview of the trademark registrations that Tiffany & Co. does – and does not have – in the U.S. is telling in terms of how it is using and describing its marks. In lieu of a registration for a simple color swatch, for instance, the company has registrations for word marks, such as “Tiffany Blue,” which it uses in connection with “jewelry featuring the color blue as an integral component of the jewelry,” and “Tiffany Blue Box” for use on jewelry. As for its other color-centric marks, Tiffany has a multi-class registration for “a shade of blue often referred to as Robin’s Egg Blue which is used on boxes” in connection with the sale of jewelry, fragrance products, certain leather goods, tableware, and stationary, among other things, as well as related retail store services.

Tiffany also has registrations for the use of its blue hue on “jewelry pouches with drawstrings” in the class of goods that extends to “jewelry” (i.e., Class 14); on shopping bags – again in connection with the sale of certain categories of goods; in connection with retail store and mail order catalog services featuring jewelry, among other things; and on metal fasteners for use on non-metal key rings.

Put simply, while Tiffany & Co. may maintain registrations for an array of uses of its blue, they are all specific – and relatively narrowly defined – and in fact, ultimately, the company’s rights are limited to the uses that it actually and consistently makes of the color, as trademark rights are born and maintained as a result of actual use of the mark and not by virtue of being issued registrations by the USPTO. As such, Tiffany is likely not standing in the way of artists using its blue hue or similar versions of the color for their work, assuming such work does not cause confusion among consumers as to any potential involvement by or affiliation with Tiffany & Co.

Still yet, it is also worth noting that based on court dockets in the U.S., Tiffany does not appear to abuse the rights that it has in its blue, and in fact, is not overly litigious, seemingly reserving the trademark lawsuits that it has initiated in recent years to fights against outright counterfeiters, such as the operators of websites like besttiffanyco.com, and Costco., which it famously sued in February 2013 for offering up non-Tiffany & Co. created rings with signage that described the rings as “Tiffany,” thereby, giving rise to consumer confusion.

Against this background, brands would be wise to take Semple’s claim that “it’s ILLEGAL for you to use [Tiffany blue] because it’s trademarked in every category” – and the notion that a trademark holder can actually enjoy such sweeping rights in a color – with a grain of salt, and focus any color-centric branding efforts on the reality that color marks are, in fact, protectable, but apply to specific goods/services, and are often relatively narrow in scope.

Hardly Semple’s first foray into taking famous hues and turning them into paint for purchase, he has made headlines in recent years after “making the blackest black paint and ink you can buy as revenge against Anish Kapoor’s control of the coveted Vantablack,” as DesignTaxi put it this week. The move followed from news back in 2014 that artist Anish Kapoor acquired the exclusive license to use Vantablack, the super-black military-grade coating, from patent owner Surrey NanoSystems. “Kapoor’s decision to withhold the material from fellow artists has sparked outrage across the international artists community,” Artnet reported at the time. Semple, included. He followed this up by making what he called the “pinkest pink,” and banning Kapoor from using it.