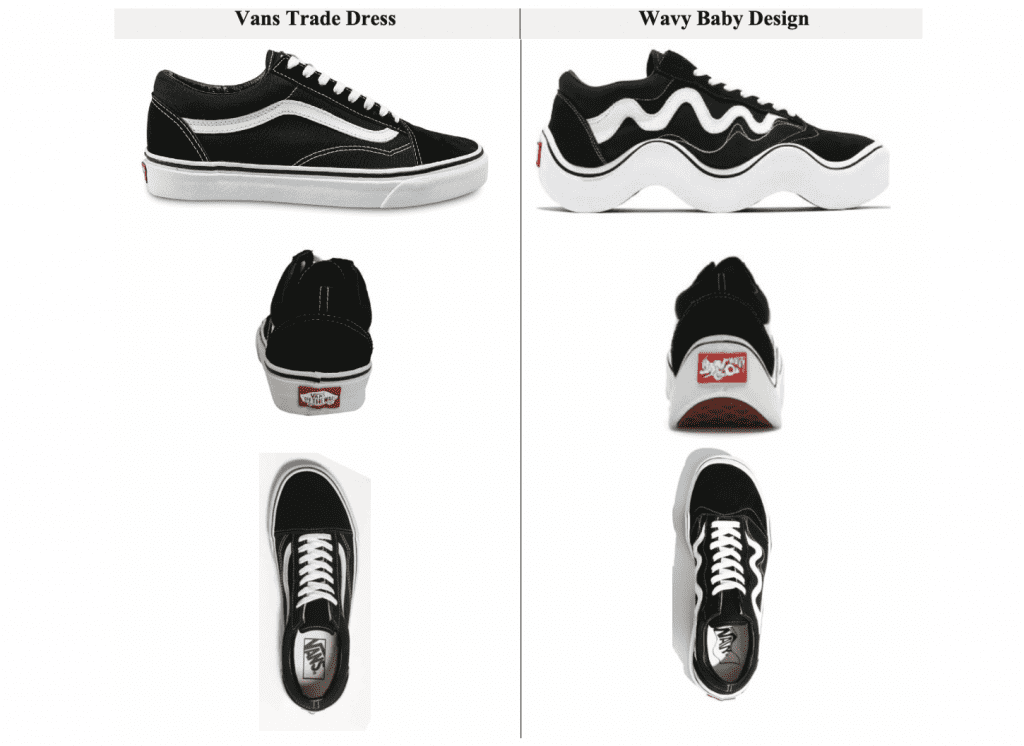

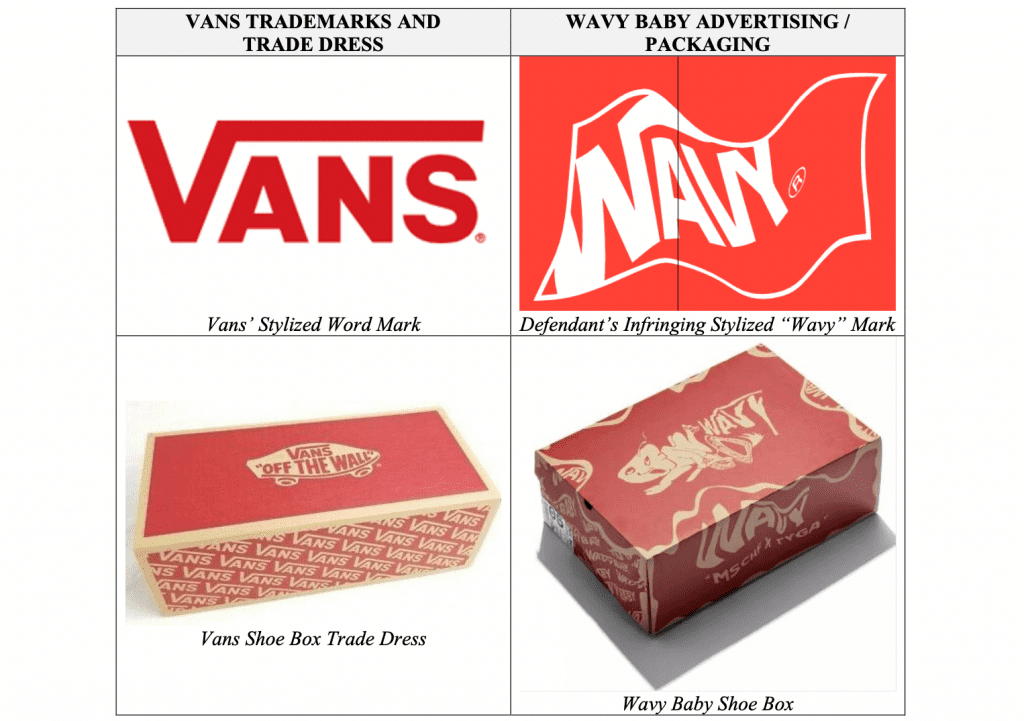

The controversial Wavy Baby sneakers courtesy of MSCHF sold out in a reported 10 minutes on Monday, just days after Vans filed a trademark infringement and dilution lawsuit against the Brooklyn-based art collective-slash-budding sneaker brand. Ahead of the launch of the allegedly infringing footwear this week, counsel for Vans filed an emergency motion for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction, arguing that MSCHF’s Wavy Baby offerings “purposefully imitate the famous and well-recognized OLD SKOOL trade dress while also incorporating numerous other Vans trademarks and indicia of source,” and thus, immediate injunctive relief is necessary to prevent irreparable harm to Vans.

In its April 15 motion and corresponding memo in support, Vans argues that the court should award it a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction to bar the release of the Wavy Baby sneakers immediately and for the duration of the case on the basis that it is likely to succeed on the merits of its claims, including trade dress and trademark infringement. Primarily, Vans argues that it maintains valid and protectable trademark rights in the appearance of the OLD SKOOL sneaker and other related marks, and that MSCHF’s Wavy Baby sneakers are likely to cause confusion, thereby, giving rise to infringement liability.

Beyond that, Vans looks to preempt MSCHF’s inevitable fair use defense (which does, in fact, follow in MSCHF’s opposition motion), arguing that the allegedly infringing MSCHF shoes “are not a parodic or artistic expression.” Specifically, Vans asserts – citing Harley Davidson, Inc. v. Grottanelli – that the Second Circuit has “recognized that parodic use or artistic alteration of a mark is ‘sharply limited’ in circumstances where, as here, ‘an alleged parody of a competitor’s mark [is used] to sell a competing product.’” Moreover, Vans argues that “parody marks also cannot, themselves, be used to indicate the source or sponsorship of a good.”

MSCHF did not release the allegedly infringing shoe “as an obvious commentary on Vans, the OLD SKOOL shoe, or some other societal issue, as is typical in a parody case,” Vans argues. “Instead, it has merely adopted the well-known and famous asserted marks and slightly altered their appearance,” which amounts to “a fast gimmick to sell shoes [that] is not a fair or artistic use of Vans’ intellectual property rights.” Vans claims that “this is particularly true [given that] Vans, itself, is known for customized versions of its shoes that retain its core OLD SKOOL trade dress, as the infringing shoes do here, and also for playful ‘skews’ of its own branding, such as placing a crooked version of the classic VANS logo on the footbed of its shoes.”

With this in mind, Vans contends that MSCHF’s “only defense is, therefore, unlikely to prevail on the merits,” and thus, the court should temporarily and preliminary enjoin MSCHF from selling the Wavy Baby sneakers until there is an adjudication on the merits.

Fast forward to Monday and MSCHF (represented by David Bernstein and Megan Bannigan of Debevoise) filed an opposition motion, arguing against a temporary restraining order. Setting the stage in the filing, MSCHF states that it is an “art collective” in the business of critiquing consumer culture, and that given its “penchant for critiquing consumer culture from within consumer culture, [it] realized that ‘sneakerhead’ culture is ripe for parody.” In furtherance of its desire to comment on “consumerism in sneakerhead culture (that Vans helped to create) and the intersection of the physical and virtual worlds (the boundary of which Vans straddles by selling ‘digital shoes’ and other ‘digital skate gear’ in the metaverse),” MSCHF introduced the Wavy Baby project, which consists of “a limited-edition series of 4,000 wearable artworks.”

Against that background, MSCHF argues that Vans is not likely to succeed on the merits of its trademark infringement (and dilution) claims because the Wavy Baby sneaker is “an artwork protected by the First Amendment” and “no reasonable consumer would be confused into thinking that Wavy Baby was produced or endorsed by Vans.” MSCHF claims that an injunction that prohibits it from offering up the Wavy Baby shoes “would unconstitutionally restrain [its] free speech because its parody of Vans is protected First Amendment expression.”

Allegedly wanting to comment on Vans’ venture into the metaverse by “translating virtual goods back into physical goods – and thereby flipping Vans’ project [of translating its functional skate shoes into digital goods used in games like Roblox] on its head,” MSCHF claims that the Wavy Baby project is expressive – and not explicitly confusing – and thus, “satisfies both prongs of the Second Circuit’s seminal Rogers v. Grimaldi test.”

In fact, MSCHF asserts that its references to Vans’ Old Skools are “relevant to – indeed, they are essential to – its expressive purpose,” as the Wavy Baby sneakers are “a warped rendition of Vans, rendering what could previously only be seen digitally into something physical, and critiquing consumer culture and Vans’ outsized role in that culture.” As such, MSCHF argues that the sneakers “easily clear the Rogers bar for artistic relevance, which is ‘purposely low and will be satisfied unless the use ‘has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever.’”

Pointing to precedent from the Ninth Circuit in the Bad Spaniels case, MSCHF contends that “if a $15 dog toy that pokes slight fun at a bottle of whiskey can be protected by the First Amendment, surely the use of Vans’ transformed trade dress in a $220 work of art as part of an art collective’s commentary on Vans’ role in consumerism and digital society is artistically relevant to the work.”

As for the potential that consumers will be confused about the nature of the Wavy Baby sneakers, MSCHF asserts that it “has made clear in its advertising and packaging that Wavy Baby is a collaboration with Tyga, not with Vans,” and that Vans “has failed to show a likelihood of confusion.” Moreover, “the bizarre and unconventional shape of Wavy Baby undermines any risk of confusion,” per MSCHF, “in part because Wavy Baby cannot substitute for Old Skools.” More than that, MSCHF argues that “no reasonable consumer who has any familiarity with Vans would conclude that Wavy Baby is anything but an exaggerated artwork by someone other than Vans.”

MSCHF further alleges that the law is on its side on this front, as “courts regularly find no likelihood of confusion with parodic consumer goods,” and “the more outlandish a parody, the less likely consumers are to think the trademark owner sponsored or approved it.”

Finally, MSCHF argues that injunctive relief is inappropriate here, as “Vans’ conduct establishes that it will not suffer irreparable harm from the sale of MSCHF’s limited-edition artworks.” For instance, MSCHF alleges that before filing suit, “Vans offered to allow MSCHF’s ‘drop’ of Wavy Baby to proceed as scheduled in return for a share of MSCHF’s profits; Vans also agreed to a meeting between the parties to discuss potential future collaborations.” The fact that Vans “would accept payment to allow the launch and expressed interest in future collaborations undermines Vans’ protestations about the harm Wavy Baby will cause to its brand,” per MSCHF. “It also demonstrates that any harm to Vans is not irreparable but rather compensable.”

As such, MSCHF requests that the court deny MSCHF’s application for a temporary restraining order.

While the sneakers dropped on Monday, the court has, nonetheless, issued an order to show cause for a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction, calling on MSCHF to appear show cause why Vans should not be granted a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction enjoining it from: “(1) selling to the public any of the “Wavy Baby” shoes, or any colorful imitations or reconstructions thereof; (2) fulfilling orders for any of the Shoes; (3) using Vans’ OLD Skool Dress or Side Stripe Mark, or any mark that is confusingly similar to those marks and trade dress, or is a derivation or colorable imitation or recreation thereof, regardless of whether used alone or with other terms or elements; (4) referring to or using any marks in any advertising, marketing, or promotion; and, (5) instructing, assisting, aiding, or abetting any other person or business entity in engaging in or performing any of the activities referred to above, or taking any action that contributes to any of the activities referred to above.”

The case is Vans, Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio, Inc., 1:22-cv-02156 (EDNY).