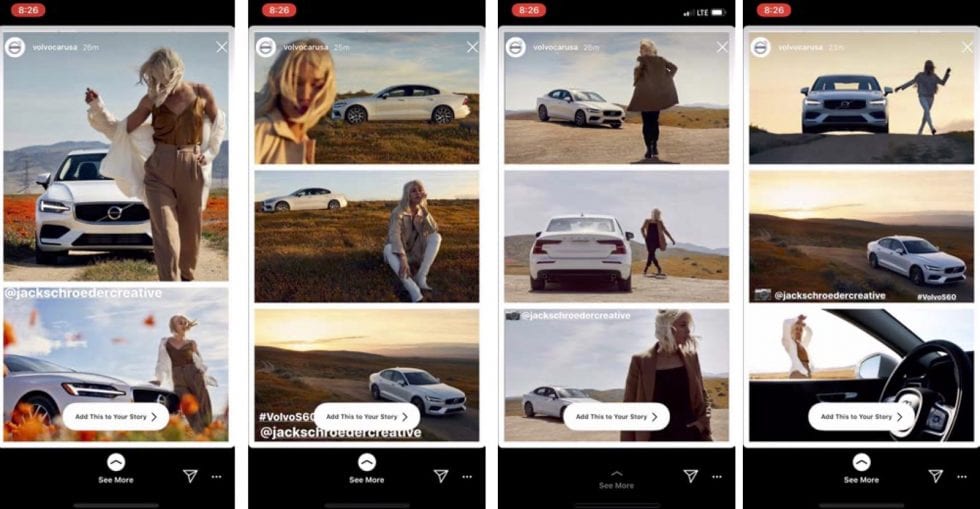

Volvo has settled a copyright-centric lawsuit after being sued in a California federal court last year for using another party’s photos for an alleged Instagram ad campaign. Photographer Jack Schroeder and model Britni Sumida accused the Swedish automaker of copyright infringement for using photos that Schroeder had taken of Sumida posing alongside a Volvo S60 as part of “a global advertising campaign” on Instagram without their authorization. After unsuccessfully attempting to get Volvo to cease its use of the images, Schroeder and Sumida filed suit in June 2020, setting out claims of copyright infringement, unfair competition, and misappropriation of likeness, with the latter resulting from Volvo’s unauthorized use of images featuring Sumida.

In response to the lawsuit, Volvo filed an unsuccessful motion to dismiss in August, arguing that Schroeder and Sumida are actually the ones who were in the wrong due to their use of the Volvo “brand, image, reputation and substantial social media reach of a venerable automotive company to promote themselves professionally.” Volvo asserted that the plaintiffs’ claims that it “impermissibly shared [the] photographs and misappropriated Sumida’s image rights as part of an unauthorized ‘global advertising campaign’ are false and disingenuous,” as there was “no such advertising campaign.” Instead, Volvo claimed that it “simply used basic social media sharing/publishing platform features to re-post” Schroeder’s images of its S60 sedan “after Schroeder and others had already published (and tagged Volvo in) the photos on their own public social media accounts.”

The crux of Volvo’s argument was that by posting the photos on Instagram in the first place, Schroeder granted it an implied license to re-post the photos in accordance with Instagram’s licensing terms.

Beyond that, Volvo claimed that “by tagging [it] in the subject photographs’ – and sharing them with Volvo, “Schroeder granted [it] an implied non-exclusive license to share the photos on Instagram and on other social media sites.” Pointing to case law from the Ninth Circuit, Volvo stated that such a nonexclusive license “may … be implied from conduct,’” which is precisely what it happened in the case at hand, per Volvo, when Schroeder made the images accessible to the public and tagged Volvo in them.

On the heels of the court denying Volvo’s motion to dismiss after it refused to take judicial notice of an array of exhibits relied upon by the car-maker, Volvo filed its answer in September 2020, denying the bulk of the plaintiffs’ claims and setting out a handful of claims of its own. Primarily, Volvo (somewhat head-scratchingly) accused Schroeder and Sumida of trademark infringement for posting photos that “prominently displayed and featured Volvo’s name, Volvo’s distinct, trademark-protected logo, and a motor vehicle that bears unique design features immediately identifiable with Volvo’s brand and line of automotive products.” Because they tagged Volvo in posts featuring the S60 sedan, the car co. declared that “anyone searching for Volvo … would be able to find these photographs and videos” and could be confused “as to the source, origin, endorsement and sponsorship of the Volvo.”

Specifically, Volvo alleged that “the infringing posts misrepresented to consumers and the automotive industry that Volvo had engaged Schroeder and/or Sumida to conduct the shoot and had authorized [them] to commercially exploit the images therefrom as part of a social media advertising campaign for the S60 Sedan.”

Volvo also accused the Schroeder and Sumida of trademark dilution on the basis that it “works closely with a carefully selected group of advertising agencies and other professionals in the U.S. to develop marketing campaigns and messaging,” and that they “diluted Volvo’s famous, distinctive marks by appropriating the substantial investment Volvo made in its marks.”

Fast forward to December 23 and counsel for Schroeder and Sumida alerted the court that the parties have “reached a settlement of this matter in full,” that a formal settlement agreement is being circulated between the parties for review and approval, and that the parties expect to file a stipulated dismissal of the entire action with each party bearing their own attorneys’ fees and costs.

Issues Over Instagram Imagery

This case may be on the brink of coming to a close, but it, nonetheless, raises one of a number of questions that have come hand-in-hand with allegedly unauthorized use of imagery first posted on Instagram and other social media platforms. The overarching issue centers on Instagram’s terms and whether they provide users with a license that could shield them from copyright infringement liability should they use images first shared on its platform without the copyright holder’s consent. This has seen brands like Volvo come under fire for resharing copyright-protected imagery to their own accounts, but maybe more commonly, cases have come about in connection with publications’ practice of embedding imagery into online articles using social media sharing tools without the copyright holders’ authorization, prompting claims of copyright infringement.

In terms of embedded imagery, this issue has been at the center of an array of cases in furtherance of what Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz PC’s Craig Whitney recently called “one of the most hotly litigated issues in copyright law over the past two-plus years.” In one noteworthy case, Nicklen v. Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc., a New York federal district court found that the unauthorized re-posting of copyright protected content online could run afoul of copyright law by infringing the copyright holder’s exclusive right to display the work regardless of whether a copy was created and stored on the alleged infringer’s own server – or whether the image was re-posted by using Instagram’s API.

In reaching his decision, Judge Jed Rakoff of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit’s “server test,” giving rise to a potential circuit split, as the Ninth Circuit “generally holds that embedding content from a third party’s social media account only violates the content owner’s copyright if a copy is stored on the defendant’s servers,” per Morrison Foerster’s Aaron Rubin, Julie O’Neill & Anthony M. Ramirez. (And Judge Rakoff is not the first SDNY judge to do so; Judge Katherine Forrest shot down the server test in a 2018 decision in Goldman v. Breitbart News Network.)

Shortly after Judge Rakoff denied Defendant Sinclair Broadcast’s motion to dismiss, a San Francisco federal court sided with Instagram in a proposed class action lawsuit, in which photographers Alexis Hunley and Matthew Brauer alleged that the social media site engaged in a “scheme to generate substantial revenue for its parent, Facebook, Inc.,” – now Meta – “by encouraging, inducing, and facilitating third parties to commit widespread copyright infringement.” According to the plaintiffs, Instagram is secondarily liable for copyright infringement for “encouraging third party online publishers … to use the embed tool [on its app] to display copyrighted works without [the necessary] license or permission from the copyright owners,” and in the process, has “misled the public” into believing that “anyone is free to get on Instagram and embed copyrighted works from any Instagram account, like eating for free at a buffet table of photos.”

In a decision in September, Judge Charles Breyer of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California held that Instagram is not on the hook for copyright infringement because its embedding tool does not require a website publisher to store a copy of an image or video, thereby, upholding the Ninth Circuit’s server rule.

Some of these squabbles – and potentially, new cases – over social media and the use of copyright-protected imagery are expected to carry into 2022, as companies, copyright holders, and courts continue to grapple with these issues.