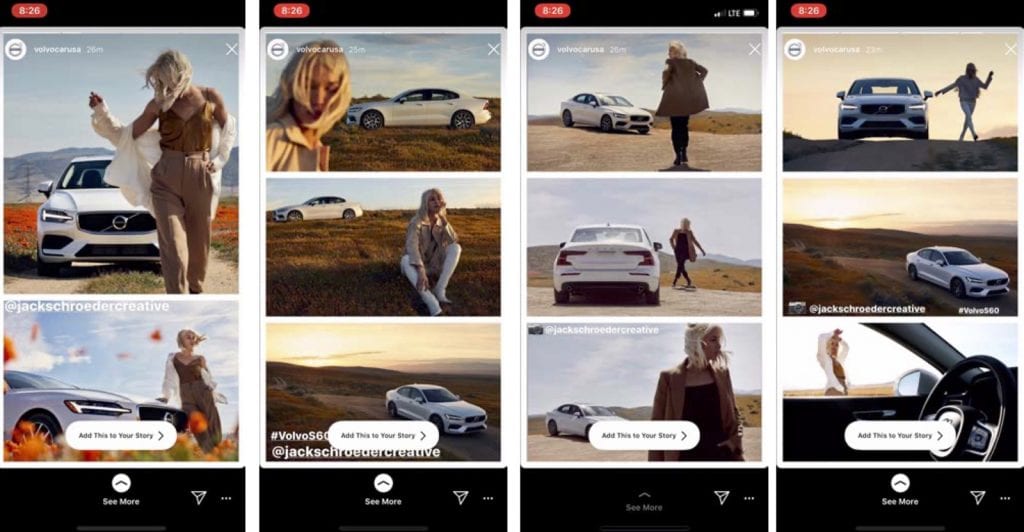

In June, Jack Schroeder and Britni Sumida filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Volvo. In the complaint, which was filed in a California federal court, Schroeder, an “automotive and lifestyle photographer,” claims that he organized a photo shoot in April 2019 that featured Sumida, a “highly sought after model,” and a Volvo S60, and was set against the background of the “super bloom” of wildflowers in the high desert of Southern California. After the shoot, Schroeder posted a number of the images that he took on his Instagram account.

“In addition to the positive response from his followers,” Schroeder claims that he “received a glowing Instagram comment from Volvo, requesting permission to use the images in its advertising.” After seeing the comment from Volvo, Schroeder emailed the automaker stating that “while he was flattered that Volvo liked the images, he does not license his work for free.” In an attempt to “build a relationship with Volvo, and to entice them to purchase his work, Schroeder provided a link to his personal website, which included additional images from the shoot that had not been posted to Instagram.”

Schroeder claims that when he never heard back from Volvo, he assumed that the car company “had simply lost interest in using his images.” However, as he would learn six months later, that was not the case. In November 2019, Schroeder alleges that Volvo began running “a global advertising campaign” on social media “to increase sales, attract new customers, and enhance its brand goodwill.” The “campaign” – which was featured in Volvo’s Instagram Stories and on its Pinterest account – “inexplicably consisted solely of the nine photographs that [Schroeder] had posted to his Instagram account, as well as two photographs that he posted to his personal website, including images featuring Ms. Sumida.”

Despite his attempts to get Volvo to remove the images at issue on copyright infringement grounds, Schroeder argues that the car company continued to do use them, thereby, “irreparably tarnishing [the plaintiffs’], diminishing the value of their work, and causing decreased revenue in the future.” This is not only true for Schroeder, but the complaint alleges that Volvo’s “unauthorized commercial exploitation of the photos is particularly damaging [to] Ms. Sumida [because she] had been hired to star in an ad campaign for a different major car company, and her contract contained a provision preventing her from working for other auto manufacturers.”

With the foregoing in mind, the plaintiffs assert claims of copyright infringement, unfair competition, violations of California Civil Code, and misappropriation of likeness (the latter is in connection with Volvo’s use of images featuring Sumida without her authorization), and are seeking monetary damages, as well as injunctive relief.

Volvo’s Motion to Dismiss

As set out in a motion to dismiss filed on August 10, Volvo wants the suit tossed out in its entirety, arguing that Schroeder and Sumida “try to make a mountain out of a molehill as they continue to exploit the brand, image, reputation and substantial social media reach of a venerable automotive company to promote themselves professionally.” Volvo asserts that their claims that it “impermissibly shared Schroeder’s photographs and misappropriated Sumida’s image rights as part of an unauthorized ‘global advertising campaign’ are false and disingenuous,” as there was “no such advertising campaign.”

Instead, Volvo claims that it “simply used basic social media sharing/publishing platform features to re-post” Schroeder’s images of its S60 sedan “after Schroeder and others had already published (and tagged Volvo in) the photos on their own public social media accounts.”

The crux of Volvo’s motion to dismiss is that Schroeder and Sumida’s complaint overlooks critical language in Instagram’s Terms of Service. To be exact, Volvo states that pursuant to Instagram’s Terms, “whenever an Instagram user [publicly] shares, posts or uploads photos or videos, that user grants Instagram a broad, royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable license in and to that posted content … to host, use, distribute, modify, run, copy, publicly perform or display, [or] translate” that content and/or to “create derivative works [based on such] content.” That license, Volvo argues, is then granted to other users from Instagram in a sublicense capacity, thereby, enabling them to re-share the imagery on the app.

Beyond that, Volvo points to additional Instagram policies, such as its “Privacy Policy,” arguing that “Instagram users were advised that when they post content (e.g., a photograph) publicly on Instagram, other Instagram users are granted a royalty-free, non-exclusive license to re-share that user content.” Specifically, the Privacy Policy states, in part, that when a user publishes content on Instagram on a non-private account, “other users may search for, see, use, or share any of your user content that you make publicly available through the [Instagram] service.” The same policy also states, “Once you have shared User Content or made it public, that User Content may be re- shared by others.”

Against this background, Volvo asserts that Schroeder’s copyright infringement claims fall short. “Simply put, when Schroeder created his Instagram account, he agreed to and became bound by Instagram’s Terms of Use, Data Policy, Privacy Policy, and other terms of service,” which grant non-exclusive licenses to Instagram and to other Instagram users, such as Volvo, “to re-share [users’ publicly-shared] Instagram photographs.”

Volvo also argues that “by tagging Volvo in the subject photographs’ – and sharing them with Volvo, “Schroeder granted [it] an implied non-exclusive license to share the photos on Instagram and on other social media sites.” Pointing to case law from the Ninth Circuit, Volvo states that such a nonexclusive license “may … be implied from conduct,’” which is precisely what the car company argues happened in the case at hand when Schroeder made the images accessible to the public and tagged Volvo in them.

As a result of the (alleged) non-exclusive license created by Instagram’s terms and by Schroeder’s behavior, Volvo asserts that it did not infringe the photographer’s copyright interests when it re-shared the photos, and thus, the copyright claim – and Sumida’s claims, which are allegedly preempted by the Copyright Act – should be dismissed.

Larger Trends at Play

Interestingly, there are a couple of larger trends at play in Schroeder’s suit against Volvo, namely, stemming from Volvo’s argument that Instagram’s terms provide licenses to users that can potentially shield them from copyright infringement liability. This is the same general argument that has been at the center of a number of embedding-focused cases that have played out in federal court in New York. The most recent of such cases is the one that photographer Stephanie Sinclairfiled against Mashable for embedding a photo that she took and publicly shared on her Instagram account into one of its articles without her authorization.

In response to Sinclair’s infringement suit, Mashable argued that a provision in Instagram’s terms grants it – and other publishers – the right to embed others’ copyright-protected imagery to their sites by way of Instagram’s embedding API without running afoul of the law, assuming that the imagery had been publicly-shared by the creator.

After initially siding with Mashable in April, Judge Kimba Wood of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York granted photographer Stephanie Sinclair’s motion for reconsideration in an opinion and order dated June 24 on the basis that the terms of Instagram’s “Platform Policy terms are insufficiently clear,” and that Mashable’s understanding of those terms “is not the only [potential] interpretation” at play.

Another looming pattern comes by way of the specific – and seemingly increasingly aggressive – attempts by brands, such as Volvo, but also Ferrari, to control how third-parties are using their trademarks when it comes to online imagery. In its motion to dismiss, counsel for Volvo argues that Schroeder is actually the one in the wrong here, as he created “an unauthorized ‘social campaign for Volvo Cars’ … to create the impression … that they had been hired by Volvo.” The car company asserts that the photographer and an affiliated production company “falsely represented to the public that the Super-Bloom Shoot images were created for Volvo as part of Volvo’s social media campaign for its newly released Volvo S60.”

Volvo also argues that Schroeder “exploited [its] proprietary designs and famous marks for their own commercial advantage,” presumably by including the Volvo car, complete with Volvo trademarks, in his photos. (As for the commercial advantage at play? Volvo claims that Schroeder admitted to using the imagery to “keep his portfolio up to date with images of 12 current models of cars” and that the plaintiffs “they hoped their stunt would persuade Volvo and/or its competitors to hire them for future ad campaigns.”)

If this argument sounds familiar it is because Ferrari made a similar one in connection with the case that it lodged against Philipp Plein when the German designer featured images of a pair of Philipp Plein-branded sneakers on the hood of one of his Ferraris. According to the Italian automaker, in doing so, Plein sought to “lead consumers to believe that Ferrari brand is in some way connected to [the Philipp Plein] brand” when no such affiliation exists.

In Plein’s case, the Court of Genova in Italy sided with Ferrari,holding that the purpose of the photos and the designer’s use of Ferrari’s valuable trademarks in those photos is commercial. Taken together, the images – which depict the Plein-branded shoes on the hood marked with the Ferrari logo – and the corresponding marketing messaging in the captions alerting consumers of where the shoes could be purchased “can only be explained as existing for the purpose of advertising” and bolstering the appeal of the Philipp Plein brand and its products by way of an association with Ferrari.

As for Volvo, a hearing on the matter is scheduled for September 14, 2020.

*The case is Jack Schroeder and Britni Sumida v. Volvo Group North America, LLC, et al., 2:20-cv-05127 (C.D.Cal.).