In economics, goods and services can be classified in different ways. You might be surprised to realize that you already knew this, even without knowing their classification names. Most goods and services are what we call “normal goods” – or those that you purchase more of as your income increases. For example, you might put healthier and more nutritious food in your cart, buy more shoes and clothes, or spend more on outings at restaurants and events.

Normal goods still abide the law of demand, which might feel like common sense: as the price of something goes up, the quantity – or frequency with which it is demanded – will fall. But there are some categories that violate our intuitions around supply and demand. And they do so for very different reasons. Meet Veblen and Giffen goods, the products that “break the rules.”

Needs and wants

Normal goods can be further divided into two types: necessity goods and luxury goods. Broadly speaking, necessity goods are all those things we require for everyday life – food, housing, electricity, and so on. Luxury goods, on the other hand, are those things we do not necessarily need but are nice to have. Luxury houses, fancier cars, more expensive clothes, etc. We become more able to afford luxury goods as we earn more. But as a result, they are also the first things we tend to cut when our income tightens.

For most of these products, the “law of demand” applies. That is, if a product’s price increases, people buy less of them than they did before, and demand for them shrinks. However, some types of good defy this “natural” principle.

Symbols of status and wealth

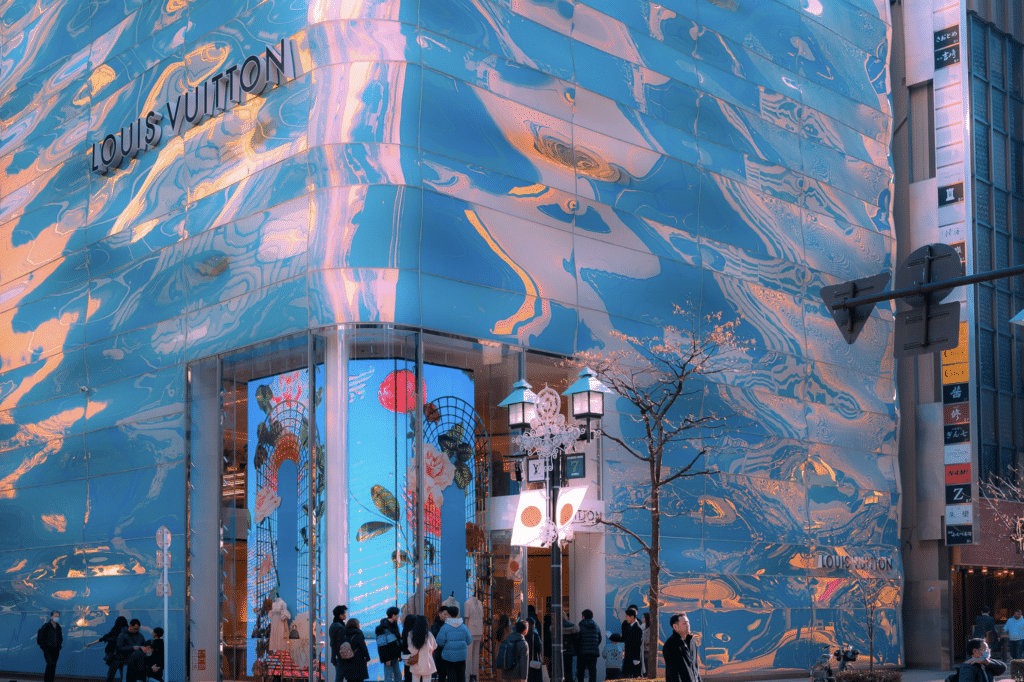

The first type are Veblen goods, named after American economist Thorstein Veblen. When these goods go up in price, demand for them actually increases. Clear examples of Veblen goods are some forms of art, high-end designer clothing and handbags (think: Hermès Birkin bags), exclusive cars, and watches. The more expensive the good is, the more exclusive it is, and the more the consumers (who are attracted to it) want to purchase it.

It all centers on signaling status. Being seen to be able to purchase them can indicate someone has exquisite taste, or lots of money to spend. Most times, Veblen goods are an example of what economists call “positional” goods. These are goods that are valued according to how they are distributed among people, and who exactly has them. The satisfaction of purchasing a Veblen good comes from the sense of having it and being able to show it off, not necessarily from how useful it is.

Inferior goods

On the opposite side of normal goods are inferior goods. As our income increases, we tend to consume less of these goods. Think, for example, of two-minute noodles or the bus service. As your income increases, you may be able to afford more nutritious and healthier food and stop consuming cheaper food. You may be able to purchase a car or a bike and stop using public transport. But within inferior goods, one rare kind offers another exception to the law of demand – Giffen goods.

Why does a rise in price cause demand to go up? Because for people on limited incomes, this limits their ability to buy substitutes. Take examples such as wheat, rice, potatoes, or bread. If the price of any of these goes up, a consumer on low income may have less to spend on higher quality goods like meat and fresh vegetables, increasing their demand for the inferior good.

María Yanotti is a Lecturer of Economics and Finance at the Tasmanian School of Business & Economics at the University of Tasmania.