A review of the case law of both the European Union Intellectual Property Office and the European Union courts issued over the period between 2020 and 2022, alone, reveals a conclusion that is likely not too shocking to anyone: less conventional trademarks remain (very) difficult to register, including when it comes to fashion. One issue on this front is the growing relevance of the absolute ground for refusal/invalidity concerning signs that consist exclusively of a shape or another characteristic that gives substantial value to the goods (Article 7(1)(e)(iii) EUTMR/4(1)(e)(iii) EUTMD). Such a ground, which was considered quite niche if not altogether meaningless for a long time, is on the rise in both frequency of application and importance.

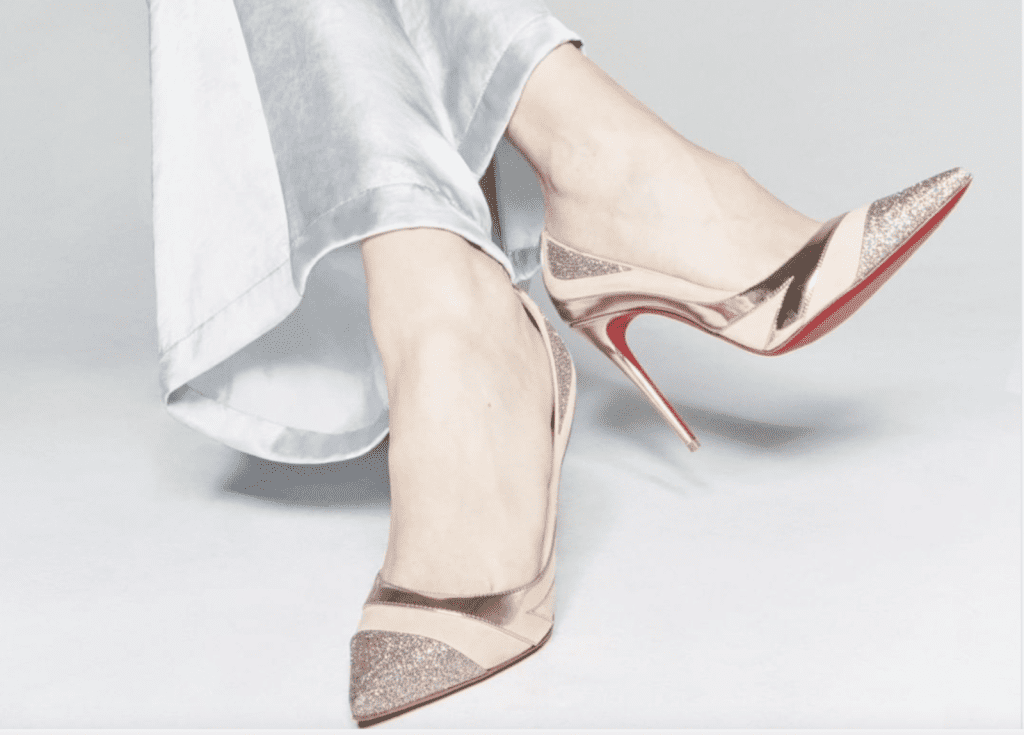

In the fashion sector, for example, French footwear brand Christian Louboutin risked losing its red sole trademark registration due to a substantial value claim (Louboutin, C-163/16). More, recently, in Gömböc, C-237/19, which centered on an application to register a three-dimensional element for use on decorative items, decorative items made of glass and earthenware, and toys, the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) clarified that substantial value is not just about being “pretty.” Factors like the story of the creation of a shape, its method of production, the materials, or even the identity of the designer can also lead to the application of this absolute ground.

In addition to the rise of the substantial value ground, another issue that is statistically still dominant for less conventional signs is distinctiveness under Article 7(1)(b) EUTMR/4(1)(b) EUTMD. For marks consisting of patterns or shapes, the threshold that trademark registration-seeking parties must meet is not an insignificant one. While the test of distinctiveness is (in principle) the same across different types of marks, for less conventional marks, consumers are not taken as being in a position to consider patterns or shapes as indicators of commercial origin, per se. As a result, as the General Court stated in a case over Louis Vuitton’s Damier pattern (i.e., a “figurative mark representing a chequerboard pattern”) only a mark that “departs significantly from the norm or customs of the sector of the goods and services at issue, and thereby, fulfills its essential function of indicating origin is not devoid of any distinctive character” (Vuitton, T-105/19).

Over the past two years, the following marks failed to satisfy the “significant departure” test …

A notable – though rather isolated – exception is, of course, Guerlain, T-488/20, a case concerning trademark of the shape of Guerlain’s Rouge G de Guerlain lipstick case as a trademark for “lipsticks” in class 3. The EU General Court concluded in July 2021 that the shape is unusual for a lipstick in that it reminds one of a boat hull or a baby carriage, and thus, it differs from any other shape on the market. Moreover, the court determined that the relevant public with a level of attention ranging from medium to high will be surprised by Guerlain’s easily-memorizable shape and is likely to perceive it as significantly deviating from the norms and customs of the lipstick sector. As a result, trademark registration would be available.

There is clear public interest justification underpinning both the substantial value absolute ground (as well as the other functionality grounds) and the approach to distinctiveness of marks consisting of things like patterns and shapes. First, there is a clear concern that allowing certain registration would pose the risk of unduly restricting competition (see, eg, Philips, C-299/99; Opinion of Advocate General (“AG”) Ruiz-Jarabo Colomer in Linde, C-53/01 to C-55/01; Opinion of AG Wathelet in Nestlé, C-215/14, and resulting CJEU judgment).

Secondly, trademark law should not become a means to extend unduly and potentially perpetually the protections available under other intellectual property rights, notably design rights and copyright (see, e.g., Opinion of AG Szpunar in Hauck, C-205/13, and resulting CJEU judgment; see also Opinion of AG Szpunar in Simba Toys, C-30/15 P). All the above said, it is possible to rely on different intellectual property rights simultaneously or at a different time to protect valuable “objects.” Again in Gömböc, the CJEU acknowledged that nothing prevents the overlap of intellectual property rights, provided that the relevant requirements under the respective regimes are fulfilled.

The fashion sector provides some recent examples in which one could successfully obtain or enforce trademarks but not copyright protections, or vice versa:

In 2020, the Italian Supreme Court found that the layout of the KIKO make-up stores would be protectable by copyright. A few years prior, seeking to follow on the footsteps of Apple, C-421/13, KIKO sought to obtain a trademark registration for its store layout but failed on ground of lack of distinctiveness. Meanwhile, in late 2021, the Milan Court accepted that Longchamps could enforce its trademark registration relating to the shape of its iconic Le Pliage bag, but refused to consider such a design as protectable under copyright.

Ultimately, like the fashion sector always strives to be creative, so should be the lawyers setting up protection and enforcement strategies.

Eleonora Rosati is Professor of Intellectual Property Law and Director of the Institute for Intellectual Property and Market Law (IFIM) at Stockholm University. (This article was initially published by IPKat).