Last month, as Chanel was filing a trademark application for the configuration of its famed Lego bag and Nike was looking to expand its stake in the “Just Do It” slogan to include a registration that extends to hair accessories, another company was seeking a registration for its own trademark. In April, one of the more than 50,000 average monthly trademark applications filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) came from a company called Shenzhen Keterui Business Technology Co. The mark? TTOOHHHJDD.

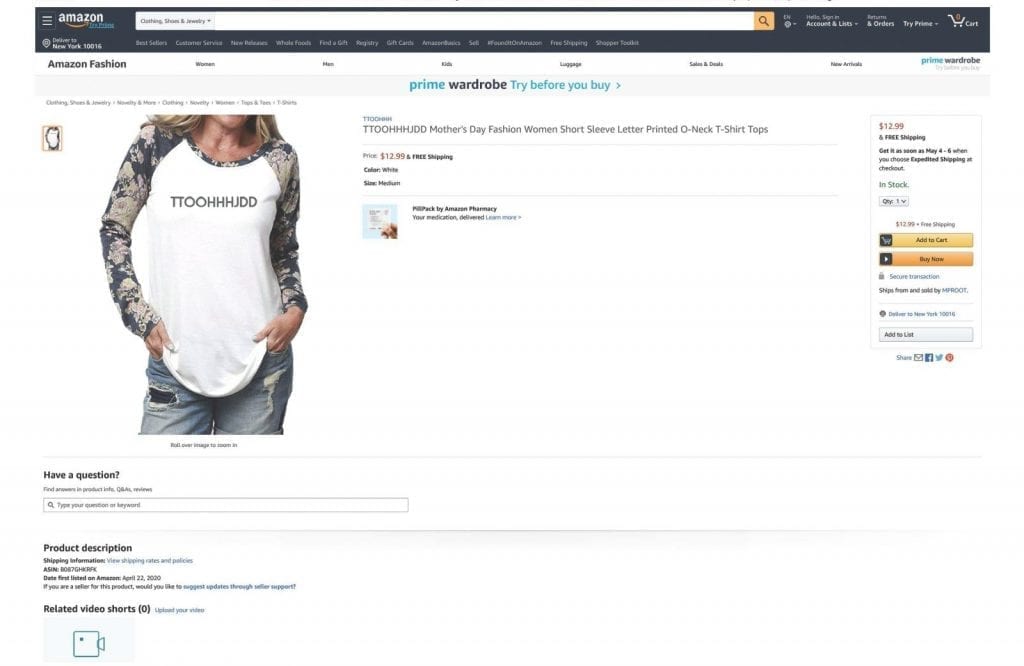

According to its application, which was identified by trademark attorney Erik Pelton, Shenzhen Keterui Business Technology Co. is already using the mark on everything from “camisoles and long-sleeved t-shirts” to “dresses and skirts,” and to prove such use (as is required before the USPTO will grant a registration), the Shenzhen City, China-based company submitted a specimen that showed a long sleeve t-shirt emblazoned with TTOOHHHJDD, which it was purportedly selling on Amazon. (When you search for “TTOOHHHJDD” on Amazon’s marketplace, nothing comes up).

You would be forgiven if you suspect that the “TTOOHHHJDD” mark looks a bit … off, especially compared to the examples of use submitted by Nike or Chanel in connection with their recently-filed trademark applications. Unlike Nike’s “Just Do It” and swoosh-adorned hair ties, for example, the image that Shenzhen Keterui Business Technology Co. provided with its application appears to consist of the word “TTOOHHHJDD” photoshopped on to the shirt. A quick image search for photos of the shirt seeming confirms this, revealing that the same white-bodied, floral-printed sleeve top is being sold on other unrelated websites without the word “TTOOHHHJDD” splayed across the chest.

Interestingly, Shenzhen Keterui Business Technology Co.’s photoshop-centric quest to amass a trademark registration is hardly an abnormality when it comes to hundreds of thousands of trademark applications that the Washington, DC-based USPTO receives every year. In fact, this instance is part of a large and ever-growing scheme, one that has caught the attention of the academics, practitioners, the Senate, and the USPTO, alike.

In December 2019, New York University Law School professor Barton Beebe testified before a Senate subcommittee about “the harm to American consumers and businesses” that is being created as a result of a very specific type of intellectual property fraud. The increasingly pervasive scheme – which largely comes out of China but which finds Amazon firmly situated at its center – sees third-party Amazon sellers duping the U.S. Trademark Office into issuing them registrations that they then use to increase “brand presence” – and thus, revenue – on the e-commerce titan’s marketplace.

As the New York Times’ John Herrman revealed early this year, in the $160 billion-plus world of Amazon’s marketplace, visibility is everything. In order to stand out among the hundreds of millions of products available with a single click (at least 12 million of which come from Amazon, itself), sellers need tools, which Amazon delivers by way of its Brand Registry. A critical venture for sellers, Amazon’s Brand Registry enables third-party sellers to reap benefits, such as “better control over their product listings” (which helps brands to fight fakes, among other things), “the Early Reviewer Program, [which allows when] to gain initial reviews on new products,” and “more access to advertising solutions.”

“To achieve real and lasting success on Amazon,” Herrman says that participation in the Brand Registry program is “vital.”

While Amazon’s Brand Registry is open to just about any third-party seller, there is one key prerequisite: In order to be eligible, a company must have a registered trademark with the USPTO and so, hordes of third-party Amazon sellers are doing just that. They are looking to the USPTO for registrations, and in an attempt to meet the requirements for registration (namely, that the trademarks for which they are seeking registrations are actually being used in commerce before such registrations may be granted), they are engaging in the fraudulent scheme that Beebe told the Senate about late last year comes in.

The enduring trademark fraud plays out a little something like this: In an attempt to get around the USPTO’s actual use requirement, many of these trademark application filers are submitting photoshopped images that appear to show how their trademarks actually being used. In other words, they are using fake specimens, and thereby, committing fraud in order to bag a registration.

What are some of the trademarks at issue? In February, Hermann pointed to largely made up and often unpronounceable words like Pvendor, RIVMOUNT, FRETREE, MAJCF, Nertpow, SHSTFD, Joyoldelf, VBIGER and Bizzliz, which are being used to sell “thousands of new product lines” and “disparate categories of goods, many evaporating as quickly as they appeared.” He also noted that some of these sellers are bringing in $1 million per month selling everything from “nail clippers, scissors and electric razors” to basic garments and accessories thanks to their dirt-cheap prices paired with the lure of free, fast shipping for Amazon Prime members, and in many cases, “driven by high search placement and customer reviews.”

The USPTO has been working to crack down on the rise in fraudulent applications, launching a pilot program in November 2018 to enable third parties to report altered or fabricated specimens that are submitted with use-based trademark applications. More recently, the USPTO has instituted changes to its trademark application, maintenance, and enforcement procedures, including requiring applicants to provide more information, such as their email addresses, and mandating that foreign applicants be represented by a U.S.-licensed attorney.

In its annual report for 2019, Andrei Iancu, the director of the USPTO, said that the national trademark and patent body has “increased investments to target possibly fraudulent/bad faith trademark application filings and to help strengthen the integrity of the Trademark Register,” making specific mention the use of “fake or altered specimens of use and false claims of use in U.S. commerce.”

Of course, such efforts have not stopped endeavoring parties, such as Shenzhen Keterui Business Technology Co., from seeking to amass registrations in their quest to earn prime placements on Amazon.