With brands increasingly engaging in social action campaigns and leveraging their influence to be “purpose-led,” the time has come to ask a couple of big questions: Is this a viable strategy, and how skeptical should consumers be of such “brand activism”? In recent weeks, alone, Ben & Jerry’s has launched a new ice-cream flavor called “Change is Brewing” to support Black-owned businesses and raise awareness of the People’s Response Act, a bill that aims to establish a new public safety agency in the U.S.

Elsewhere in the market, Lego declared it would promote inclusive play and address harmful gender stereotypes with its toys. Mars Food rebranded Uncle Ben’s rice to Ben’s Original in response to criticisms of the racial caricatures in its marketing. All the while, businesses have a checkered history when it comes to engaging with societal problems, from self-serving “box ticking” corporate practices under the guise of social responsibility to shifting responsibility to consumers to make ethical choices, such as reusable coffee cups.

More recently, “woke washing” has seen brands promoting social issues without taking meaningful action. Consider fast fashion brands that promote International Women’s Day while simultaneously profiting from the exploitation of female workers, or high fashion houses that sell expensive t-shirts with feminist messaging while at the same time, consistently maintaining boards and C-Suites that are dominated by men.

Change From Within

With the foregoing in mind, how can brands legitimately shoulder responsibility to support or promote societal transformation? Our research introduces the idea of “transformative branding,” which involves companies working with customers, communities and even competitors to co-create brands that lead on both market and social fronts. Not limited in its applicability, transformative branding can be achieved by for-profit organizations, not-for-profits and social enterprises. The common factor is balancing business and societal goals to create change from within the market system.

Socially-focused marketing concepts and campaigns have proliferated in the past 50 years, but finding actual solutions has been less successful, which requires us to ask how corporations can act to genuinely contribute to society and show how transformative branding can help brands shoulder that responsibility.

Transformative branding works via two main market-shaping elements: leadership and collaborative coupling. These enable companies to partner with stakeholders to change their business landscapes. First, leadership involves building a vision for the transformation. This requires leaders to think flexibly and creatively, work to long time horizons and stay attuned to changing ideologies. This involves fundamentally re-imagining what branding can do – beyond making money.

Second, collaborative coupling involves implementing this vision across the different dimensions of the brand. Key to this is mobilizing stakeholders, including customers, employees, investors, suppliers, governments, communities, and competitors. When a brand and its stakeholders collectively throw their weight behind the goal of transformation, it signals commitment, distributes expertise, and resources and establishes legitimacy. Leadership and collaborative coupling work together to change the business environment. Our research shows this has ripple effects, creating opportunities for transforming economic, regulatory, socio-cultural, and political environments.

Transformative Branding in Practice

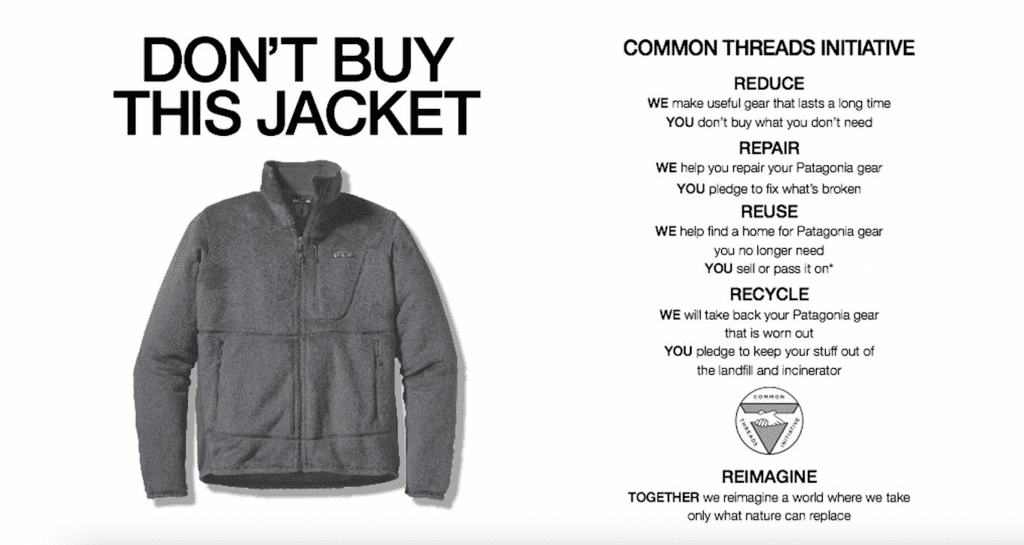

Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard is a good example of transformative branding at work, particularly in his candid admission that the notion of a fully sustainable business is “impossible.” Instead, Patagonia has reframed its priorities around responsibility, with Chouinard re-imagining the brand as a solution to environmental degradation. This vision is central to the brand’s iconic “demarketing” campaign – with the company telling consumers, “Don’t buy this jacket” – which aims to shift the consumption ideology from purchase to repair.

More recently, Patagonia’s “Buy Less, Demand More” campaign and its “Worn Wear” venture for used apparel have brought the notion of a circular economy into the company’s strategy to promote a culture of reuse rather than always buying new.

At the same time, Dutch chocolate brand Tony’s Chocolonely demonstrates collaborative coupling in its campaign to clean up production and supply chain practices in the chocolate manufacturing industry, and to eliminate illegal child labor and modern slavery. The company’s “open chain platform” helps all industry players, including competitors, to foster equitable and transparent supply chains and ensure a living income is paid to cocoa farmers. The brand actively erodes its own potential competitive advantage in the process.

Staying Skeptical

But transformative branding is complex and dynamic, and authenticity is paramount. For instance, earlier this year, Tony’s was removed from watchdog organization Slave Free Chocolate’s ethical producers list over its partnership with a major chocolate producer being sued for allegedly using slave labor. The Amsterdam-based company responded by claiming it was important to educate and inspire business partners and competitors to adopt ethical principles and practices.

The complex and often slow process of negotiating what it means to be ethical is all part of transformative branding. It adapts to the differing goals and values of many stakeholders. And while transformative branding offers a path towards a more sustainable and equitable future, we should continue to cast a critical eye on brands claiming to be a force for good, challenge them and hold them accountable where necessary.

Amanda Spry is a Lecturer of Marketing at RMIT University. Bernardo Figueiredo is an Associate Professor of Marketing at RMIT University. Jessica Vredenburg is a Senior Lecturer in Marketing at Auckland University of Technology. Joya Kemper is a Senior Lecturer in Marketing at the University of Auckland. Lauren Gurrieri is a Senior Lecturer in Marketing at. RMIT University. (This article was initially published by The Conversation.)