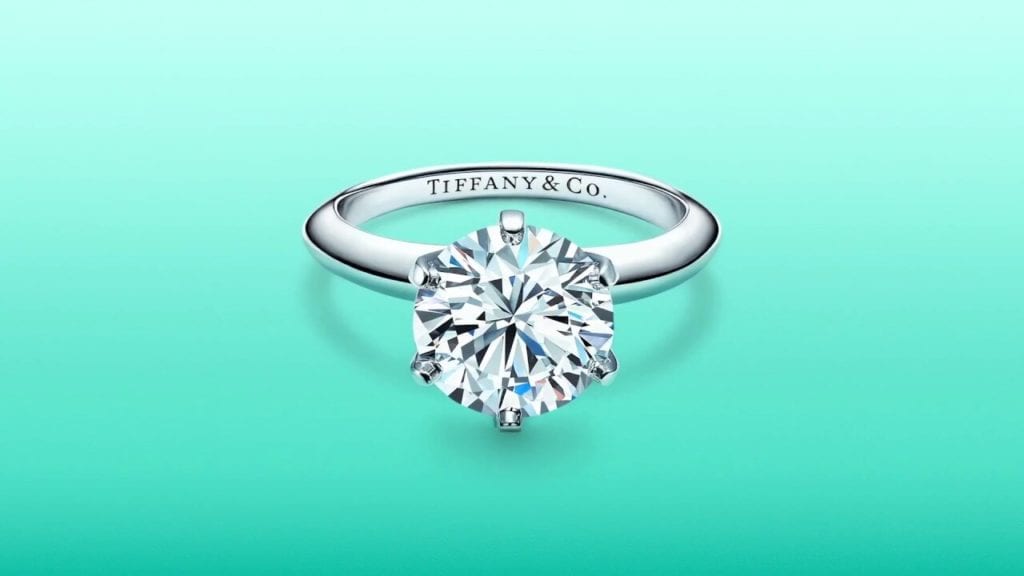

On February 14, 2013, as couples were lovingly exchanging Valentine’s Day gifts, at least some of which likely came packaged in little robin’s egg blue boxes, Tiffany & Co. was in more of a fighting mood. The jewelry company had recently learned that Costco Wholesale was selling diamond “Tiffany” rings at its sprawling outpost in Huntington Beach, California. Why was it selling its notoriously perfect-quality diamond rings at a chain of warehouse stores known for offering up bulk quantities of paper towels and $1.50 hot dog and soda combos in-store, a customer who contacted the 182-year old jewelry company wanted to know. Given that it exclusively sells its jewelry in its own stores, such as its Fifth Avenue flagship, Tiffany wanted to know the answer to that question, as well.

By mid-February, two months after it received the confused customer inquiry, Tiffany had completed an investigation and filed a lawsuit in a New York federal court. In the strongly-worded complaint, Tiffany accused Costco of trademark infringement, counterfeiting, and unfair business practices, among other causes of action, and sought tens of millions of dollars in damages. According to Tiffany, the chain had sold engagement rings – some costing upwards of $6,000 – using the “Tiffany” name to thousands of Costco members, who snatched up the sparklers under the false impression that they were authentic Tiffany products.

In a show of its own force, Issaquah, Washington-headquartered Costco, a multi-national giant that was generating annual revenues of more than $100 billion at the time (a figure that has since risen to $150 billion), responded to Tiffany’s suit, pushing back against the New York-headquartered company’s claims and lodging a counterclaim of its own. Costco argued that “Tiffany” is not a legally-protected trademark but instead, a generic term short for “Tiffany setting,” which describes a specific ring setting (i.e., a diamond solitaire situated among six prongs). With such an argument in play, Costco sought to have Tiffany’s federal registration for the mark invalidated.

The move to nullify the registration for Tiffany’s world-famous – and thus, wildly valuable – trademark for its name for use in connection with rings, and thus, rob the jeweler of its exclusive rights in the name to a certain extent, would not only shatter Tiffany’s trademark-centric case, it would likely prove a multi-billion dollar blow to the famed jewelry company if Costco could swing it, but as would be revealed in September 2015, it couldn’t.

Judge Laura Taylor Swain of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York granted Tiffany’s motion for summary judgment. In doing so, she dismissed Costco’s counterclaim and its defenses, including its claim of fair use, which centered on Costco’s claim that it was merely using the allegedly generic “Tiffany” name to refer to the setting, and not to identify the source of the rings, and thus, should be shielded from infringement liability.

All in all, the court found that Costco was liable on a whole host of grounds, including trademark infringement and counterfeiting. Costco had confused consumers with its use of signage bearing the word “Tiffany” to identify the rings in its stores, according to the court, which held that “despite [its] arguments to the contrary, based on the record evidence, no rational finder of fact could conclude that Costco acted in good faith in adopting the Tiffany mark.”

In reality, the judge determined that Costco’s conduct amounted to “gross, wanton or willful fraud,” with the retailer specifically requesting that its vendors copy Tiffany products, which it then sold in its stores.

On that basis, it would be up to a civil jury to determine the amount of monetary damages owed to Tiffany.

On September 29, 2016, a jury of New Yorker residents returned a verdict awarding $5.5 million in damages to Tiffany to compensate for the profits that Costco had made from selling the rings at issue dating back to 2007. That figure was increased a month later when $8.25 million in punitive damages were added on top of the actual damages sum in order to punish Costco for its willful bad acts. Costco walked away – that day – with a total damages bill of nearly $14 million subject to the judge’s post-verdict approval.

In a decision issued in August 2017, Judge Swain did not sign off on that figure; she increased it. Upping the ante further, she ordered Costco to pay $19 million in damages, a sum of three times the $3.7 million in profits that the retailer was found to have made from selling the infringing rings ($11.1 million) plus an additional $8.25 million in punitive damages. In handing down her decision, the judge specifically highlighted that Costco’s management “displayed at best a cavalier attitude toward Costco’s use of the Tiffany name in conjunction with ring sales and marketing.”

Unsatisfied with the outcome at the district court level, Costco filed an appeal with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in September 2017. It argued that, among other things, the court erred in its determination of whether its rings met the higher bar required for a finding of counterfeiting, as opposed to trademark infringement (a lower standard that comes with lesser penalties), and thus, it argued, the court’s decision should be reversed.

Counsel for Costco asserted that while Tiffany’s lawyers had presented evidence during trial that its use of the “Tiffany” trademark intentionally created a likelihood of consumer confusion, which is the central element in a trademark infringement claim, in order to determine whether such infringement reaches the level of counterfeiting, the trademark at play must be “identical to or substantially indistinguishable from” the rightsholder’s mark.

Costco’s “Tiffany” rings

Costco’s “Tiffany” rings

Costco argued that its use of signs bearing the word “Tiffany” to identify the multi-pronged solitaire diamond rings it was offering was not enough to give rise to counterfeiting liability, as the Costco rings had non-Tiffany trademarks on them, were sold to consumers in non-Tiffany packaging, and came with non-Tiffany paperwork. This did not meet the high bar required for a funding of counterfeiting, it asserted in the lengthy appeal filing.

In addition to putting the very definition of counterfeiting and its application on the table, the appeal – which is slated to go before the Second Circuit this year – will center on whether or not Costco’s descriptive fair use defense is persuasive, i.e., whether or not Costco’s use of the allegedly generic word “Tiffany” is a non-infringing way to “describe” a certain style of ring, as opposed to a way to identify the specific source (or brand) behind a product.

In response to Costco’s appeal, Tiffany argued in a 73 page brief filed in July 2019 that the lower court’s grant of summary judgment on the issues of trademark infringement and counterfeiting liability should stand, asserting that the retailer “intentionally used [its] famous name in point-of-sale signs to sell inferior copies of an engagement ring [style] for which Tiffany is renowned,” and even “admitted that it intentionally used ‘Tiffany’ in signs to describe otherwise unbranded rings, despite knowing that this word was a strong, world-renowned trademark, and without taking any steps to prevent consumer confusion.”

Still yet, counsel for Tiffany argued that “Costco had no proof that ‘Tiffany’ as a standalone [trademark] is generic,” nor did it show that it was “the only way to identify this particular ring style, or that it was ever popularly used [as a descriptive term] for this design.”

Finally, Tiffany claimed that Costco is “seeking reversal [of the district court’s findings] by misstating the evidence, mischaracterizing cases, and ignoring its own failures of proof.” The court should do no such thing, the brief essentially asserts, and instead, the appeals court to uphold the lower court’s findings.

Alas, Costco’s lodging of an appeal did not bring the district court’s proceedings to a screeching halt. Back before the district court early this year, Judge Swain decided a post-judgment motion from Costco that centered on the court’s accounting of the damages, including the court’s calculation of profits damages, which used a 50 percent profit margin to account for the low markups that Costco charges for its rings. She stood by the calculation, asserting that “awarding only the [actual] profits earned directly from the sale of the infringing rings would be insufficient.” So, instead, the court calculated profits damages based on the profit margin range of an average jewelry store.

And while she was at it, Judge Swain increased Costco’s tab even future, this time by $5.9 million to cover Tiffany’s legal costs, bringing Costco’s total owed to a whopping $25.25 million.

“We are gratified that Judge Swain reiterated what she has said repeatedly now, and what a jury also found, that Costco’s use of the world famous Tiffany mark to sell its own jewelry was totally improper,” Browne George Ross LLP litigator Jeffrey Mitchell told Bloomberg Law in January 2019.

Costco’s counsel David H. Bernstein of Debevoise & Plimpton LLP in New York countered, saying that “Costco looks forward to vindicating its rights in the appeal.”

As of 2020, the case is expected to be decided by the 3-judge panel for the Second Circuit.

*The case is Tiffany and Company v. Costco Wholesale Corporation, 0:17-cv-02798 (2nd Cir.), 1:13-cv-01041 (SDNY).