A new Birkin bag-centric trademark scuffle may be in the making. Toronto-based designer Xylk Lorena claims that his Instagram and Shopify accounts were recently shut down – putting a temporary stop to his promotion and sale of the sako bags emblazoned with images of Hermès Birkin bags on them that he debuted in 2022. While Lorena told Highsnobiety that he “never received a cease-and-desist letter [from Hermès]” nor was he contacted by a brand representative, he says that “they” – presumably Hermès – “had Instagram just take down our account, [and] Shopify sent me a letter … [saying] we used copyrighted [err – trademark-protected] names, but we never did.”

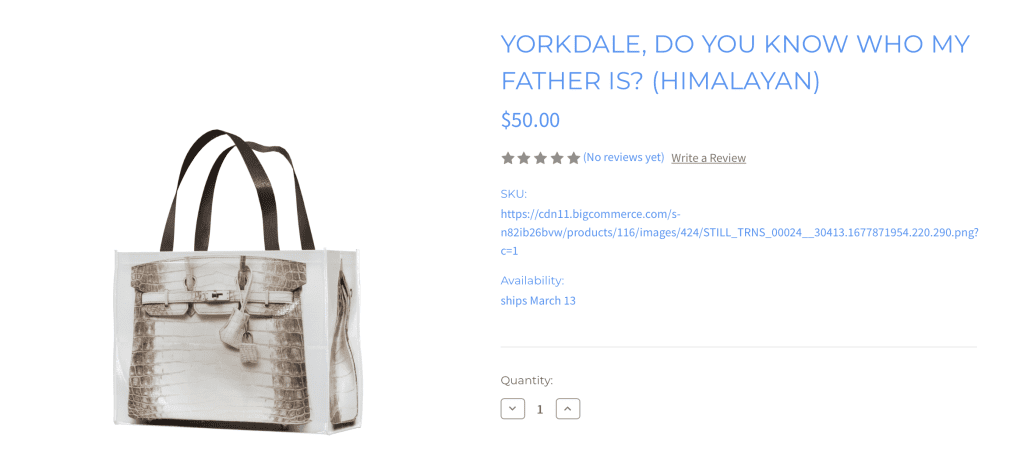

Lorena has since created a new Instagram account (@grocerybags.grocerybags) and his e-commerce site remains up and running, where a handful of the $50 “Grocery Bags” are available for purchase. Reflecting on the bags, he told Highsnobiety this week that they are a comment on the way the luxury brands operate: “It’s classism built on racism. Like, we’re gonna make everyone want this but only a certain type of person can have it? The Grocery Bags are me saying, ‘No, we can have it too.'” As for potential ramifications (namely, trademark infringement, dilution, etc.), Lorena is not worried, “I never use any copyrighted intellectual property, like the bag shapes or hardware. I’d say we’re good under fair use and parody laws.”

Merits of any parody arguments aside, the scenario – one that Highsnobiety’s Jake Silbert characterizes as an example of how “a new generation of fashion-conscious creators bend established fashion codes as they see fit” – is nothing if not déjà vu. It comes just over ten years after Hermès took action against a canvas tote bag-maker called Thursday Friday, Inc. (“TF”), lodging a federal and state law false designation of origin, trademark infringement, and trademark dilution case against it in New York federal court.

Hermès v. Thursday Friday

According to Hermès’ January 2011 complaint, the now-defunct TF was offering up cotton tote bags bearing images of Birkin bags on them, which it called the “Together Bag.” In doing so, Hermès argued that TF was “simply riding on the reputation and recognition of the Birkin bag to sell its otherwise generic tote bags,” and was “creating confusion among the public” who would believe that the TF bag was “either sold by or has been licensed, sponsored or endorsed by” Hermès, and was “putting [Hermès’] reputation at risk” in the process.

As for its trademark rights in the appearance of the Birkin bag, Hermès alleged that since the famed handbag “does not bear any visible word trademark on its exterior or on any hangtags sold with it … and as a result of the enormous sales, extensive advertising and promotion and ubiquitous publicity and attention in the press and media, the design of the Birkin bag has acquired secondary meaning and has become a famous trademark associated exclusively with [Hermès].” It noted that its rights in the design of the Birkin bag “have been judicially tested and approved by cases, such as Hermès International v. Lederer de Paris, Inc. and Pelle Via Roma, in which two separate juries found that the design of the Birkin bag had acquired distinctiveness and was infringed by a knockoff bag.”

Following a failed motion to dismiss (the court found that Hermès had alleged “a legally sufficient claim for relief), TF filed an answer and affirmative defenses with the court, arguing that, Hermès claims were bared because it “did not make use of the Birkin bag trademark or the Birkin closure trademark as a trademark” and “did not use photographs of any product made by [Hermès], nor any copyrighted material whatsoever, for the artwork on the sides of the Together Bag.” TF additionally asserted that while Hermès uses the words “‘Hermès Paris’ on the Birkin closure and elsewhere” – and that this is the “primary means for consumers to identify the Birkin bag’s source,” the Together Bag does not contain any of Hermès’ word marks. And “the absence of these word trademarks on any other bag than those made by [Hermès] is sufficient to distinguish it as one not made by or affiliated with [Hermès].”

Beyond that, TF alleged that even if it did use Hermès’ marks, it “intended to create – and successfully created – a parody of those marks,” and its use of the marks amounts to fair use. And still yet, TF argued that Hermès’ claims should be blocked because: (1) it did not create any consumer confusion by way of its Together bags; (2) Hermès “suffered no damage as a result” of the bags; (3) the Birkin bag mark is functional; (4) its use of the Birkin bag image on its bag “is ornamental and not a designator of source:” (5) the Birkin bag mark is not famous enough to merit protection from dilution; and (6) the Birkin bag “does not have secondary meaning separate and apart from the word trademarks that appear on it.” The parties ultimately settled the case before there were any other substantive developments.

Louis Vuitton v. My Other Bag

The issue of well-known handbags being depicted on inexpensive canvas totes arose again a few years later, of course, when Louis Vuitton sued My Other Bag (“MOB”), only to have the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirm the district court’s grant of summary judgment for MOB. In that case, which could serve to embolden creators of a new generation (like Lorena), MOB was offering up “canvas tote bags bearing caricatures of iconic designer handbags on one side and the text ‘My Other Bag . . .’ on the other,” as the court characterized them. While Louis Vuitton did not get the joke, according to the court, the MOB bag “was inspired by novelty bumper stickers, which can sometimes be seen on inexpensive cars claiming that the driver’s ‘other car’ is an expensive, luxury car, such as a Mercedes.”

(Among other things, Louis Vuitton took issue with MOB’s parody defense on the basis that it was commenting on a larger social issue, and thus, not specifically targeting the Louis Vuitton brand. “This argument was effective in a recent case involving a Hyundai advertisement,” CDAS stated in a note at the time. “However, as the district court clarified (without comment from the Second Circuit), even if MOB’s products convey a message about luxury brands, generally, a parody defense is, nonetheless, available to MOB because MOB’s products parody Louis Vuitton’s goods specifically at least in part.”)

The court found that MOB’s parody was obvious, and the “whole point was that the tote bags were not the luxury goods being parodied,” Dorsey & Whitney LLP’s Sandra Edelman and Kaleb McNeely stated at the time. MOB’s win raised some interesting issues regarding the parody defense, they asserted, noting that “the court emphasized My Other Bag’s intent to parody, but did not delve into the question of whether consumers received this message from the bag. The court obviously got the joke, but was there evidence that consumers did as well? If not, is it really parody?” They also questioned whether “the purveyors of high-end designer products just have to accept that their products are going to be the lawful target of satire on the ground that the ‘commentary’ required for the parody defense is self-evident?”

The backlash that Louis Vuitton faced in connection with the MOB case (from the media and the court) for “not being able to take a joke” seemed to indicate that brands have a fine line to walk when it comes to enforcement, especially given that such public-facing efforts may generate more attention that rights holders want. (Ultimately refusing to award attorneys’ fees to MOB, SDNY Judge Furman asserted in 2018 that while Louis Vuitton may be an aggressive enforcer of its rights, the defendant “does not point to any concrete evidence suggesting that Louis Vuitton was solely, or even primarily, motivated in this case by an improper desire to chill parody or stamp out a smaller competitor,” and he noted that the court is “sensitive to the fact that the law compels trademark owners to police [unauthorized uses of] their marks or risk losing their rights.”)

THE BIGGER PICTURE: The “Grocery Bags” remind us of the enduring tension felt by brands that need to enforce unauthorized uses of their trademarks, while also being cognizant of First Amendment-centric defenses and the prospect of backlash should consumers view brands as being hyper-litigious. As Judge Furman put it in the Louis Vuitton v. MOB case, “In some cases, it is better [for trademark holders] to ‘accept the implied compliment in a parody’ and to smile or laugh than it is to sue.”

What that balance actually looks like can be difficult to discern, particularly in light of recurring arguments by defendants when trademark holders are seemingly lax in their enforcement. During trial for the MetaBirkins case, for example, counsel for Rothschild pointed to instances in which Hermès allegedly did not enforce unauthorized uses of its marks, including projects by Tom Sachs and Tyler Shields, in its defense. At the same time, counsel for By Kiy recently argued in response to a lawsuit waged against it by Nike that the Swoosh has done “very little to police” some of its marks. In particular, By Kiy points to sneakers from Amiri, Rhude, Golden Goose, and Saint Laurent that “incorporate many, if not all, of the purported trade dress elements” of its Air Jordan 1 and/or Dunk trade dress, but that Nike has allegedly never claimed were infringing.

Given the value of the trademarks at play and the speed of the modern news cycle, which often serves to diminish the staying power of bad PR, it is worth considering whether such litigation-borne risks are still as … risky. What is clear is that at least some players seem to be relatively undeterred. The potential for bad press has not stopped the likes of adidas, which continues to enforce its three-stripe marks (the Thom Browne case comes to mind), for instance, or Nike, which has been taking action against customizers’ unauthorized uses of its trademarks, prompting ire among the sneakerhead community. Meanwhile, Chanel is suing resellers, thereby, giving rise to at least some claims that its behavior is aimed at chipping away at the secondary market, and then there is Hermès, which recently prevailed against Mason Rothschild at trial over the latter’s creation and sale of “MetaBirkins” NFTs tied to digital artworks that mimic the design of its most famous bags.