image: Culture Shock Art

A Chanel suit lined with acetate trim, instead of silk. A Louis Vuitton bag bearing slightly asymmetrical “LV” initials in the brand’s monogram toile pattern. An Hermes bag with off-kilter stitching. These are some of the counterfeits with which the fashion world commonly deals. But long before vendors set up shop on Canal Street and before online marketplaces began offering fakes online, forgery ran rampant in the art world. And unlike the thousands of dollars that came to be tied to counterfeit fashion purchases, art fakes have been known to invoke multi-million dollar schemes.

Just six years ago, for instance, the most significant case of art fraud in American history began to unravel. The story goes a little something like this: New York art dealer Glafira Rosales – a “well-dressed and cultivated” women of 40 – walked into M Knoedler & Co. (“Knoedler”) with a Rothko painting.

The Making of an $80 Million Dollar Art Scheme

The gallery’s director Ann Freedman – who joined Knoedler in the late 1970’s when she was 29 years old and swiftly rose through the ranks to become president and then director of the gallery by the early 1990’s – “was dazzled” by the Rothko, per Vanity Fair. “After consulting experts, she felt it was clearly authentic, though its story was, admittedly, sketchy. Rosales said she had a friend who wanted to consign the work to Knoedler. The friend wanted to stay anonymous.”

This was the first meeting between Freedman, who had just taken over the directorial role of the gallery, and Rosales, “a woman from Long Island [that] no one in the art world had ever heard of,” according to ArtNews. Rosales came to meet with Freedman by way of Jaime Andrade, a Knoedler associate, who was been brought on board years prior by Larry Rubin, the director that made way for Freedman’s promotion when he left in 1994.

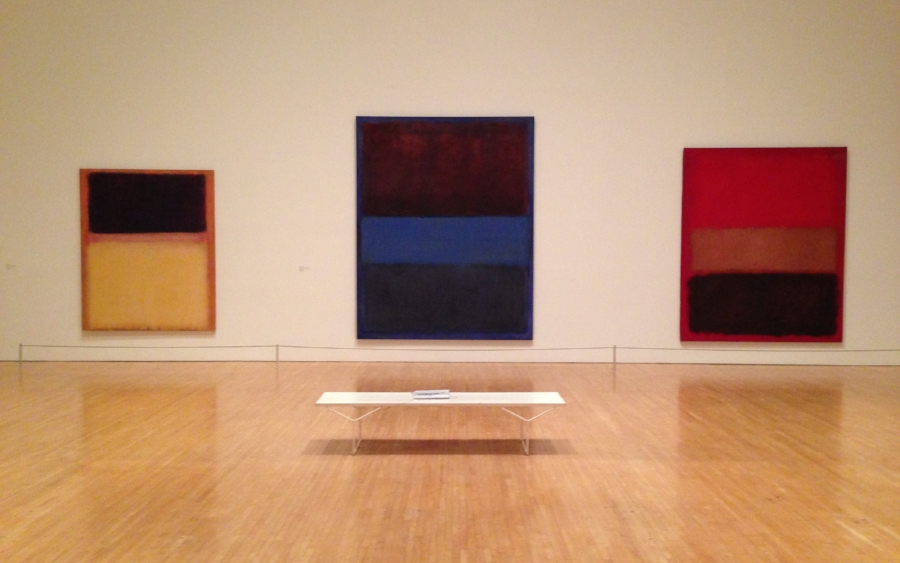

Rosales – with the alleged help of her boyfriend, Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz; his brother Jesus Angel Bergantinos Diaz; and Pei-Shen Qian, a successful Chinese artist, and the individual who did the actual painting – would go on to spearhead a 15-year, $80 million forgery scam, blindly fooling art collectors into buying counterfeit paintings attributed to the likes of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and Willem de Kooning from Knoedler.

One such collector: Chairman of the board at Sotheby’s and former Gucci Group CEO Domenico De Sole, the brilliant lawyer and businessman who, along with creative director Tom Ford, took the Italian design house from a nearly bankrupt entity in the early 1990’s to wildly profitable venture in just a decade. It was under his watch that Gucci managed to artfully fend off a hostile takeover by LVMH head Bernard Arnault and land under the umbrella of LVMH’s rival conglomerate Kering.

As laid out by ArtNews last year, “On a trip to New York in November 2004, [Domenico and his wife Eleanore De Sole] visited the Knoedler & Co. gallery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan for the first and last time.” Mr. De Sole had just cashed out of Gucci, pocketing roughly $25 million by selling some 433,101 shares in nine separate transactions that year.

Having opened in 1846, Knoedler was one of the United States’ oldest and most widely-known commercial art galleries, initially rising to fame as a leading supplier of Old Master paintings to the likes of Cornelius Vanderbilt, J. P. Morgan, and Henry Clay Frick.

The De Soles “went there to inquire about buying a work by artist Sean Scully, who had been represented by Knoedler off and on for years, and met with Freedman, the gallery’s president. She told them she did not have any work by Scully available, but she did have a painting—right there in her office—that she said was by Mark Rothko,” according to ArtNews.

Freedman explained to them that “a private Swiss collector had owned the work, and that his family wanted to remain anonymous.”

The anonymous collector – whose paintings Rosales was consigning to the gallery – was initially known around the gallery as Mr. X. “The provenance of the work was always murky,” per the Washington Post. Rosales allegedly told Freedman that she was representing a man – Mr. X. – who resided between Mexico and Switzerland. He allegedly inherited the paintings from his parents, but the identity of this private collector was never revealed.

“As Freedman remembers it, Rosales said Mr. X.’s Philippines-based parents had known Alfonso Ossorio, an Abstract Expressionist painter,” wrote Vanity Fair. “Supposedly Ossorio brought the couple to artists’ studios, where they purchased paintings from the artists directly. The paintings remained in storage until their son inherited them, so none appear in the catalogues raisonnés of the now dead artists.”

But as ArtNews notes, “By the time the De Soles arrived at Knoedler, Freedman was using the late David Herbert to explain the origins of the Rosales works. Herbert, who died in 1995, was a former low-level employee at the two leading New York galleries that showed the Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s, Sidney Janis and Betty Parsons. The story became richer when Herbert’s name was floated in connection to the paintings: Mr. X and Herbert had engaged in a love affair. This was why the collector, who was married and had a family, wanted his name to be kept secret.”

After short deliberations (and confirmation in writing from the gallery that the Rothko had been “viewed” by 11 different experts, most of whom have since said they did not consent to being included on this list and denied having seen the painting for any meaningful amount of time), the De Soles opted to purchase the Rothko from Knoedler for $8.3 million.

As the story unfolds, that painting – “Untitled (1956)” – was fake, as were 39 other expertly crafted paintings that Ms. Rosales supplied to the gallery under Freedman’s watch.

A Highly-Followed Trial

“More than a decade after [their] meeting [with Freedman] at the gallery, and two years after their Rothko was revealed to be a fake, the De Soles would tell a jury that Freedman and Knoedler had knowingly conned them out of seven figures,” writes ArtNews.

The De Soles had filed a $25 suit against Knoedler, its holding company 8-31, Freedman, Rosales, and others in a New York federal court 2012, alleging violations of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, among other statutes, in connection with what they called a coordinated pattern of fraud that lasted for years.

The weeks-long trial focused largely on “questions about what efforts were made to verify the authenticity of the works and who was aware they were forgeries—and, of equal importance, when.”

The De Soles emphasized in their testimony that Freedman should have exercised more due diligence to verify “Mr. X” and the authenticity of art works. They further argued that they relied heavily on the fact that they were dealing with “the most trusted, oldest, most important gallery,” a common argument across the ten lawsuits filed in connection with the gallery’s alleged fraud.

Private equity manager, John Howard, another plaintiff that sued Knoedler after purchasing a forged Willem de Kooning work, said: “Here I am dealing with the Knoedler gallery, one of the most prestigious galleries in the U.S., founded before the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Howard’s suit settled before trial.

The defendants countered, arguing that as sophisticated entities, the plaintiffs should have known to independently verify the authenticity of the work before purchasing it. Moreover, Freedman’s counsel, who vehemently denied that their client was aware that the paintings were, in fact, counterfeit, noted that Freedman purchased a few of the forged works, herself.

In February 2016, after two weeks of trial and before its culmination, the case was settled out of court; the terms, confidential. “The De Soles are extremely pleased and not surprised that Ms. Freedman settled after two weeks of trial evidence showing that, for 15 years, Knoedler ignored the most eminent experts, buried unhelpful research, made up stories about where works came from, earned profit margins that virtually announced the fraud, hid the truth, and lied to collectors, like the De Soles, to sell fakes and make millions,” the De Soles counsel said in a statement to Artnet.

The De Soles settled with Knoedler and the gallery’s holding company, 8-31, days later.

The Others

As for the others, who earned more than $33 million thanks to the elaborate scheme, according to prosecutors: Qian, who was charged criminally for creating the counterfeit works, fled to China, where he is safe from U.S. authorities due to the lack of a U.S.-China extradition treaty. Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz, who fled to Spain thanks to his status as a dual Spanish-American citizen, was also charged and, as of February 2016, was awaiting extradition from Spain. Rosales pleaded guilty in 2013 to several criminal charges and early this year, was sentenced to nine months of house arrest and three years’ probation, and is required to pay $81 million to the victims of the fraudulent scheme.

According to the Art Newspaper, as of April 2017, “Seven of the ten Knoedler lawsuits have been settled. The Hilti Foundation settled with Freedman, but its lawsuit against Knoedler is still active. A claim brought against both Knoedler and Freedman by Frances Hamilton White, over a Jackson Pollock she and her then-husband bought in 2000 for $3.1 million, is ongoing.”

Meanwhile, just three blocks from the now defunct Knoedler gallery on New York’s Upper East Side, Freedman maintains her own gallery, Freedman Art, which she opened after resigning from Knoedler in 2009.