Deep Dives

In October 2021, Nike got the ball rolling. By filing trademark applications for registration for its name, swoosh logo, and a number of other well-known marks for use in connection with “downloadable virtual goods,” “retail store services featuring virtual goods,” and “entertainment services, namely, providing on-line, non-downloadable virtual footwear, clothing,” etc., the sportswear titan garnered widespread media attention and prompted a large number of other big-name companies to follow suit and file applications for their marks for use in the “quintessential” web3 classes of goods/services (i.e., classes 9, 35, and 41, as well as 36 and 42.)

As TFL previously reported, the steady stream of metaverse-related filings seems to suggest that companies are hedging their bets in light of uncertainty about the burgeoning metaverse and tech like NFTs – from what they might do in this space to how courts and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) will treat their existing “real world” trademark rights/registrations when it comes to web3 tech and the virtual world.

From that wave of web3 filings, another trend appears to be emerging: Companies and products are being branded with metaverse/crypto-specific prefixes and suffixes. The most famous example on this front is likely MetaBirkins, the name of the controversial NFTs that Mason Rothschild released in December 2021.

While Rothschild has not filed a trademark application for the term MetaBirkins (and likely will not given the arguments that are being made in the case that is being waged against him by Hermès over the allegedly infringing NFT project), a growing number of others have filed applications for marks in this same vein. Applications for METAJACKET and METAMALL, for instance, were filed by Nike-owned web3 brand RTFKT; an unrelated third party filed an application for METAKICKS; OTB Group-owned brand Amiri is seeking a registration for METAMIRI; and applications for METACOFFEE were filed by a “real” world coffee company. All of these applications – and others like them – point to uses (or more commonly, intended uses) on metaverse/crypto-focused goods/services.

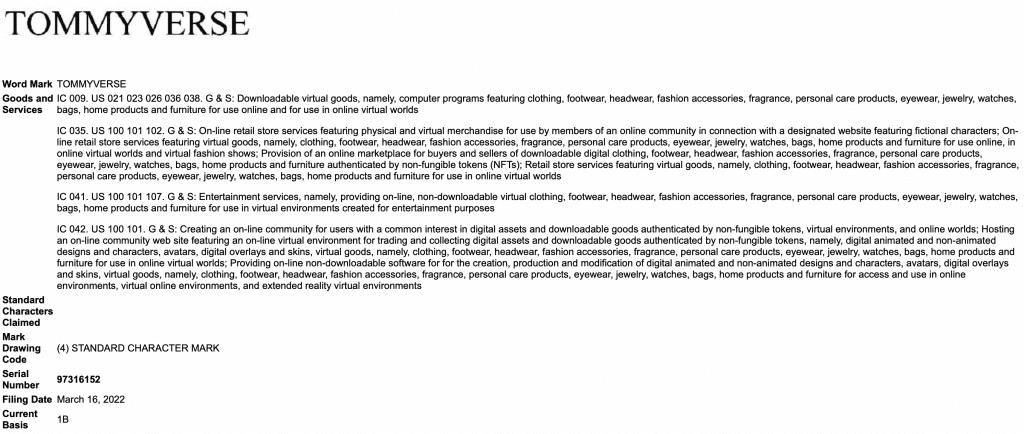

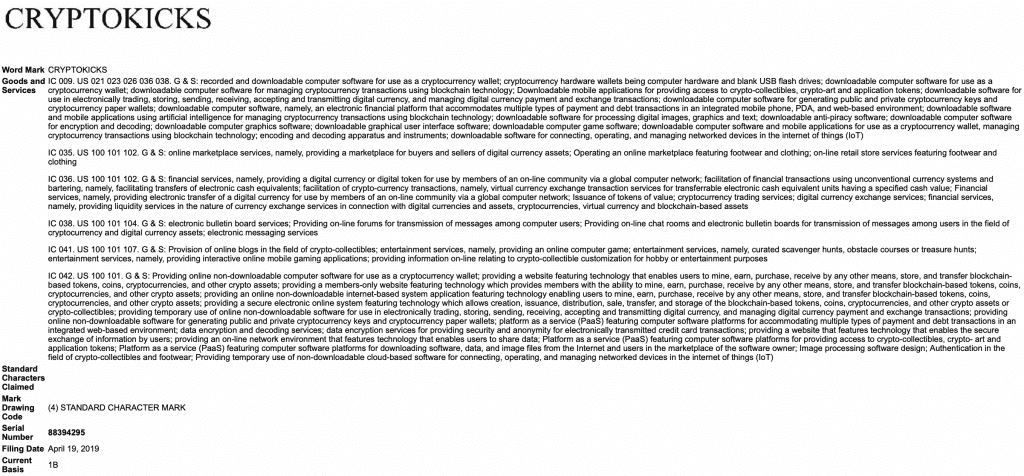

Not limited to the “meta” prefix, the trend extends to the “crypto” prefix. Nike has filed applications for CRYPTOKICKS, for example, while other parties are seeking web3-focused registrations for marks like CRYPTOCOTTON, CRYPTOCONCERTS, CRYPTOJACKET, etc. And beyond that, there is the “verse” suffix, with companies ranging from Ulta, PacSun, and Tommy Hilfiger to Bape, Yeezy, Hypebeast, and Moda Operandi filing applications for marks that add the suffix to their names for use in the metaverse and/or in connection with NFTs.

It is will interesting to see what courts and the USPTO make of such marks – and their ability to indicate source in the virtual world.

So far in the MetaBirkins case, Hermès has taken issue with the “meta” suffix, arguing that that consumers are likely to be (and already have been) confused as to the source of Rothschild’s similarly-named NFTs. Specifically, counsel for the French brand has asserted that Rothschild’s “MetaBirkins brand simply rips off Hermès’ famous BIRKIN trademark by adding the generic prefix ‘meta’ to the famous trademark BIRKIN.” According to Hermès, “Meta” refers “to virtual worlds and economies where digital assets such as NFTs can be sold and traded,” and thus, the term as a whole “simply means ‘BIRKINS in the metaverse.”

Instead of helping to distinguish his NFTs from the Hermès brand, counsel for Hermès has maintained that Rothschild’s use of the “meta” prefix does the opposite and creates “the explicitly misleading impression that Hermès, the only source of Birkin handbags, is offering Birkin handbags in the METAverse.”

(Rothschild has argued in response that he has “the right to identify his depictions of Birkin bags as ‘MetaBirkins’ – a name that both refers to the context in which he makes the art available (i.e., the online, virtual environment popularly dubbed the ‘Metaverse’) and alludes to his artwork’s ‘meta’ commentary on the Birkin bag and the fashion industry more generally.”

As for insight from the USPTO, most of the applications for web3 prefix/suffix marks are still awaiting examination but a few developments are worth noting: Nike was granted a notice of allowance in April 2020 for its CRYPTOKICKS mark, including for use in connection with “operating an online marketplace featuring footwear and clothing; on-line retail store services featuring footwear and clothing,” sans any substantive Office Actions.

On the “meta” front, the USPTO registered RTFKT’s METAJACKET mark in January for use on “downloadable virtual goods, namely, articles of clothing, featuring jackets, coats, anoraks for use in online virtual worlds,” and granted a notice of allowance to RTKFT in December 2021 for the METAMALL mark – again without any pushback (as we dove into here).

Meanwhile, a November 2021 application for METACOFFEE filed by Miami-based Coffee Worldwide, LLC has not fared quite as well (yet?). In an Office Action this month, the USPTO preliminarily refused to register the mark for use in connection with “retail store services featuring virtual goods, namely, coffee bags, coffee products, coffee merchandise, coffee equipment for use in online virtual worlds,” among other things, on the basis that it is merely descriptive. The issue, according to the USPTO examiner, is that “when the applied-for mark is taken as a whole and considered in connection with the identified services, it is immediately descriptive … because it conveys, without any ambiguity, a feature, characteristic, purpose and/or function of applicant’s services, namely, virtual coffee- related services in the metaverse, or metacoffee.”

What might prove to be even more interesting than the individual outcomes of these applications is the fact that these web3-focused marks are not a novel phenomenon. In fact, in conjunction with the advent of the internet, companies did similar things on the branding front, including by adopting web-centric marks – and in many cases, filing web-focused applications for them. Disney, for example, filed an application for registration in 1995 for “Disney Online” for use in connection with “computer services, namely, providing on-line information in the fields of education and entertainment.”

Hardly the only example, in the early 90s, companies like PBS, Miriam Webster, Oracle, Comcast, OfficeMax, Ticketmaster, and Advance Publications, just to name a few, filed applications for marks that consisted of their brand names (or in the case of Advance the names of its publications, such as Vogue, GQ, Glamour, Vanity Fair, etc.) along with the word “Online” at the end. (Many of these applications were met with some initial pushback from the USPTO, which called on the companies to clarify/amend the goods/services at issue, more-or-less mirroring the same messages that are currently coming from examiners in response to the many web3-related applications.)

The fates of such “Online” marks have been mixed from a registration perspective. Some of the applications – including those from Disney, Comcast, and Advance – were abandoned. Others were registered and subsequently cancelled (think: OfficeMax Online, Smithsonian Online, etc.) And at least a few remain in force to an extent. PBS, for example, still has a registration for “PBS Online,” for use on “educational services; namely, interactive multimedia databases and other computerized services such as visual and voice programming.”

From the perspective of actual (and meaningful) use, it does not appear that the rush to register these marks has really panned out. Search results for “Disney Online,” for instance, currently leads to an old-school-looking homepage that simply directs users to go to Disney.com, where Disney is not making use of the “Disney Online” mark. The “online” bit kind of goes without saying. This does not necessarily support an argument in favor of the flood of “[Brand Name] Online” marks being valuable assets for the brands.

The other examples cited above do not appear to be in use as trademarks at all, and instead, these companies have opted to use their well-known marks (Vogue, Comcast, Ticketmaster, etc.) in a web capacity on their own. As it turns out, brands do not need to add web-specific terms to the end of their names/marks to indicate to consumers that they are operating on the web; that consumer-facing messaging seems as though it was driving at least part of the initial push to secure rights in/registrations for the “[Brand Name] Online” marks.

If history is teaching us anything here, it is likely that the same will be true for the marks that fall within the new metaverse and crypto-related naming convention – and that save for some potential exceptions (such as CRYPTOKICKS and some of the other marks that Nike and RTFKT have already starting using), brands will ultimately use their word marks – on their own – in connection with web3 endeavors. That has not stopped brands from rushing to the USPTO and other trademark offices to try to register such marks, though, and so, I will continue to watch this space.