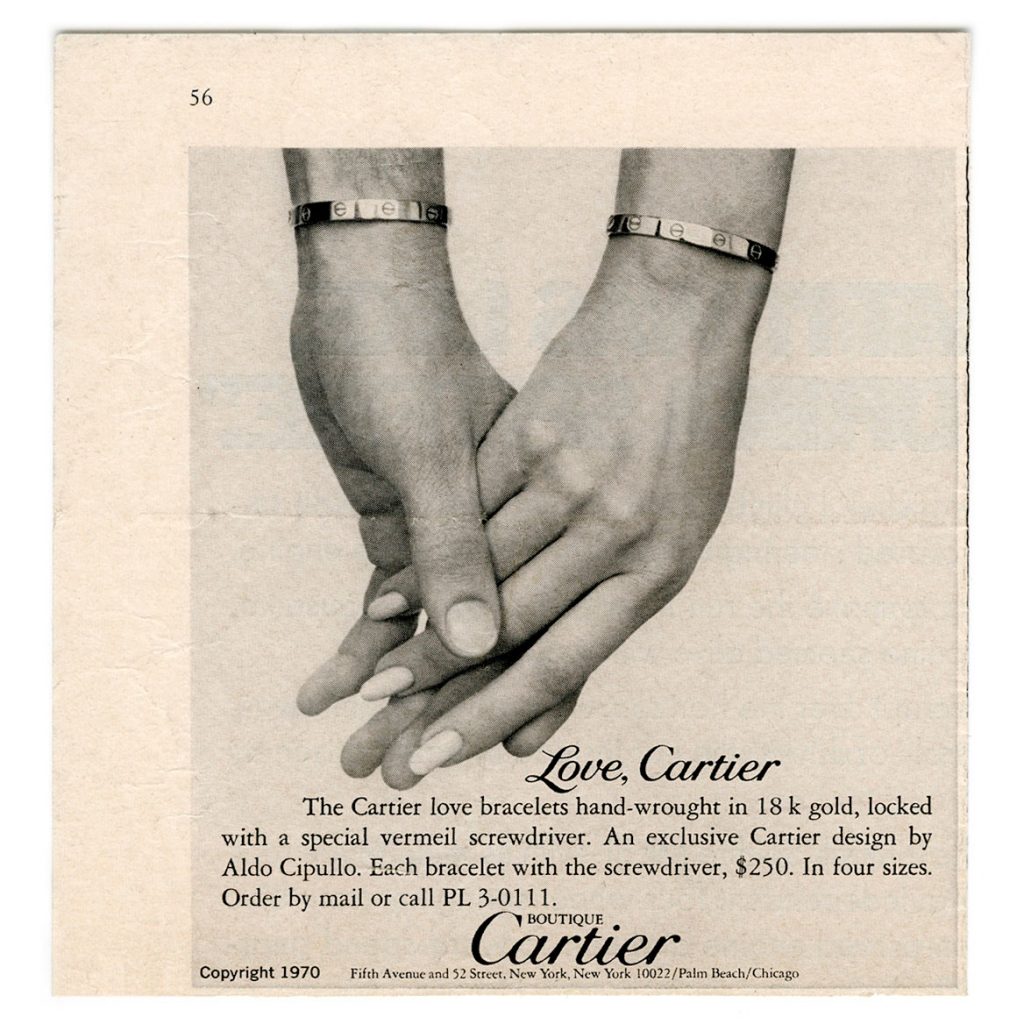

One of the most – if not the most – readily sought-after Cartier bracelet style is held together by two little screws that, when tightened, lock the precious metal bangle on to the wearer’s wrist. According to the nearly 175-year old French jewelry-maker, this gilded bit of bondage is meant “to sanctify inseparable love.” Practically speaking, given the price tags associated with these designs, those start at $4,500 and go up from there, they also “signify high incomes,” as AdWeek aptly characterized the 1970s status symbol-turned-pricey ”millennial must-have.”

When the Love bracelet was first released by Cartier in 1969, the creation of Italian-born American jewelry designer Aldo Cipullo, it swiftly became something of an intriguing purchase for well-to-do consumers, helped, of course, by powerful celebrity endorsements, such as those of couples like Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and Sophia Loren and Carlo Ponti.” When Revlon executive Frank Shields – father to actress Brooke Shields’ – exchanged Love bracelets with his second wife Diana Lippert instead of rings in 1970, the shift in jewelry gave rise to the question in the media, ‘Will the Love bracelet replace the wedding band?,'” the Adventurine recalls. “Even the Duke and Duchess of Windsor exchanged Love bracelets in the seventies.”

Originally priced at $250 and reportedly sold only to couples, the Love Bracelet design, itself, remains relatively unchanged more than 50 years later – albeit the bracelets now come in three alloys of gold (which can cost upwards of $50,000 in some cases) and are now sold individually. Cartier has also since released a slimmed-down version of the Love bracelet, as well as an array of diamond encrusted options.

As for, the bracelet, itself, with its two unique C-shaped halves that unhinge to clasp together before being screwed on with the miniature screwdriver included with each bracelet, it still functions in exactly the same manner, and in recent years, that very design has enjoyed a mainstream resurgence of sorts, thanks, at least in part, to a new batch of high profile and highly influential wearers. In place of Elizabeth Taylor and Sophia Loren are Kylie Jenner and Rihanna.

Love and Legal Protections

Given the staying power of the Love bracelet, and Cartier’s practice of aggressively protecting its valuable designs, the jewelry company maintains an array of legal protections in connection with it, thereby enabling its legal counsel to police unauthorized attempts to replicate the iconic design, whether it be the hoards of Amazon sellers offering fake Love bracelets for little more than $30 or higher-end jewelry companies doing their best takes on the time-tested classic.

Cartier’s enforcement efforts are founded, to a large extent, on its trade dress rights in the bracelet. A subset of trademark law, trade dress protection extends to the appearance of a product, assuming that such a configuration indicates the source and distinguishes it from other sources. Given the longstanding and consistent use of the Love bracelet by Cartier and the sheer level of fame associated with the bracelet, its design, and its source, Cartier’s trade dress registration for the overall appearance of the Love bracelet not only makes sense (certainly the jewelry company can show that the bracelet maintains to requisite level of secondary meaning in the marketplace), but is a valuable form of protection.

Registered in 1977 and renewed as recently at 2007 (trade dress and trademark protection can, in theory, last indefinitely subject to periodic renewals), this specific registration protects “the overall configuration of a bracelet having a series of simulated screws which encircle the goods and two real screws, which appear at the points on the bracelet where it may be opened” in Class 27. An identical registration was issued in 1985 in Class 28, which broadly covers “amusement and game apparatus” and “equipment for various sports and games.”

Aside from the trade dress registrations, there are a number of other registrations in the mix for the Love bracelet, as well. For instance, the famed jeweler has trade dress rights in the design of “a jewelry item with a series of simulated heads of screws embedded around the outside perimeter.” Another extends to “a configuration of a simulated head of a screw that is embedded in the goods.” Still yet, Cartier maintains a trademark registrations for a “stylized version of the word LOVE,” which covers classes 14, 18, and 25, jewelry, leatherware, and apparel, respectively. And these are just a few examples of the protections that exist in Cartier’s sweeping Love-centric portfolio.

Cartier: A Vigilant Defender

Far from merely accumulating such registrations and any common law (i.e., state law) rights in its world-famous bracelet, Cartier actively enforcers those rights. It is, after all, the trademark holder’s duty to police unauthorized uses of its marks in order to maintain the exclusive source-identifying capabilities of its trademarks (and ensure the continued value of those marks, which translates, in many cases, to premium pricing).

In addition to the many run-of-the-mill trademark infringement and counterfeiting cases that Cartier (and almost every other luxury brand) files each year, Cartier has initiated an array of more interesting legal matters in connection with the Love bracelet, and the word “Love,” as well.

For instance, in early 2014, Cartier took on the World Gold Council in an attempt to prevent the market development organization for the gold industry from federally registering its own “LoveGold” trademarks. By way of an opposition lodged with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”)’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Boar (“TTAB”), Cartier argued that the World Gold Council should not be able to register its “LoveGold” mark because it is “confusingly simliar in sound, meaning, appearance, and commercial impression” to Cartier’s “Love” marks and thus, when used in connection with jewelry would “likely cause confusion or mistake or deceive the purchasing public” into believing the two companies’ goods are related when they are not. With that in mind, Carier argued that it would “be damaged by the issuance of a registration for the marks LoveGold.”

The back-and-forth between Cartier and the World Gold Council before the TTAB continued through early 2015 before Cartier withdrew its opposition, seemingly in light of a settlement between the parties, and following initial approval from the USPTO in 2015, LoveGold’s marks were formally registered in 2018. All the while, Cartier and its parent company, Swiss conglomerate Richemont, were in and out of court in the United Kingdom in furtherance of a bigger fight: a case that would require internet service provider (“ISP”) companies – including defendants BT, Virgin Media, Sky, TalkTalk and EE – to block access to websites offering for sale and selling counterfeit and otherwise infringing versions of its watches and jewelry.

Unsurprisingly, one of most heavily-targeted jewelry products under the Richemont jewelery umbrella when it comes to counterfeits is Cartier’s coveted Love bracelet.

Ruling in favor of Cartier and Richemont July 2016, the England and Wales Court of Appeal confirmed a lower court’s finding that ISPs do, in fact, have an obligation to block sites infringe others’ trademarks. The court stated that while the responsibility to identify the offending websites lies primarily with brands, ISPs have a legal responsibility to cooperate in disabling them, thereby sharing the burden of combating the sale of counterfeit goods online with the brand owners. The win was a big one, and the outcome has been deemed a “landmark” victory.

As for the claims from counsel for the ISPs that its quest to block websites that offer up counterfeit goods “restricts freedom of speech [and otherwise] legitimate activity,” Cartier’s parent pushed back. “This action is about protecting Richemont’s maisons and its customers from the sale of counterfeit goods online through the most efficient means,” a spokesman for the conglomerate revealed. “It is not about restricting freedom of speech or legitimate activity.”

After all, it is those very protections that have enabled Cartier to remain the easily-identifiable source of these coveted bracelets in the minds of consumers. And that level of exclusivity – paired with famous endorsements and oft-out of reach price tags, which do not drop too far below their original retail price on resale sites like The RealReal, which implies enduring demand – plays a signifiant role in how Cartier has been able to continue to sell the Love bracelet, decade after decade.

*This article was initially published in June 2019.