Nowadays, fashion’s buzziest “wars” are often fought on Instagram, whether it be claims of copying or backlash involving allegations of cultural appropriation. Look past this inherently click-able content and you will see a larger, more significant battle underway behind the scenes: one that involves some of the market’s largest manufacturers, which are busy squaring off in an effort to build up billion dollar rosters of big brand names to gain (or maintain) the wildly lucrative title of “leader” in the realms of cosmetics, fragrances, and eyewear.

Some of the key players in this fight are names you may know. There is Coty, L’Oreal, Puig, Perfumania, and Inter Parfums. There is Euroitalia, Marcolin and Marchon, and still yet, not to be overlooked, Safilo, and Essilor-Luxottica, to name a few. Even if you do not know these names, if you own a pair of luxury-branded sunglasses or just about any fashion fragrance, you have come in contact with their offerings.

Here’s why: take that Prada Eau de Parfum being stocked by Sephora, for instance, or the Chanel eyewear being offered up on the brand’s website. While these products bear the brands’ names and logos, they were not actually made, marketed, or distributed directly by those brands. Instead, one of the aforementioned companies was responsible for that as part of a highly lucrative licensing deals, one that sees a brand (or licensor) trade off the right to use its name and logo on certain goods categories to a company like Coty (the licensee) generally in exchange for a hefty fee and then recurring royalties based on sales.

Given the brand names and potential revenues at stake, it does not go unnoticed whenever one of these licenses changes hands. For example, L’Oreal announced this spring that it was well on its way to becoming “the world leader in perfumes.” The tipping point? Its “win” of the Valentino fragrance license.

In May, the Paris-based beauty firm revealed that it will produce fragrances and cosmetics for Italian fashion label Valentino, enhancing its own perfume business roster by scoring a license previously held by fellow cosmetic giant Puig. The latter, a Spanish fashion and fragrance business, currently has dibs on the right to exclusively make, market, and claim a portion of the revenues for fragrances (and in some cases, other beauty products) bearing the Prada, Comme des Garcons, Nina Ricci, Paco Rabanne, Carolina Herrera, Christian Louboutin, and Jean Paul Gaultier names, among others.

L’Oreal’s move to lure Valentino away from Barcelona-based Puig – which announced in early 2010 that it had partnered with the Italian fashion brand as part of “a multi-year worldwide license agreement involving the creation, development and distribution of luxury fine fragrances under the Valentino brand” – is par for the course in this ongoing game of licensor/licensee. But far from merely a small-stakes pastime, the business of licensing is a multi-hundred million dollar per brainpower play.

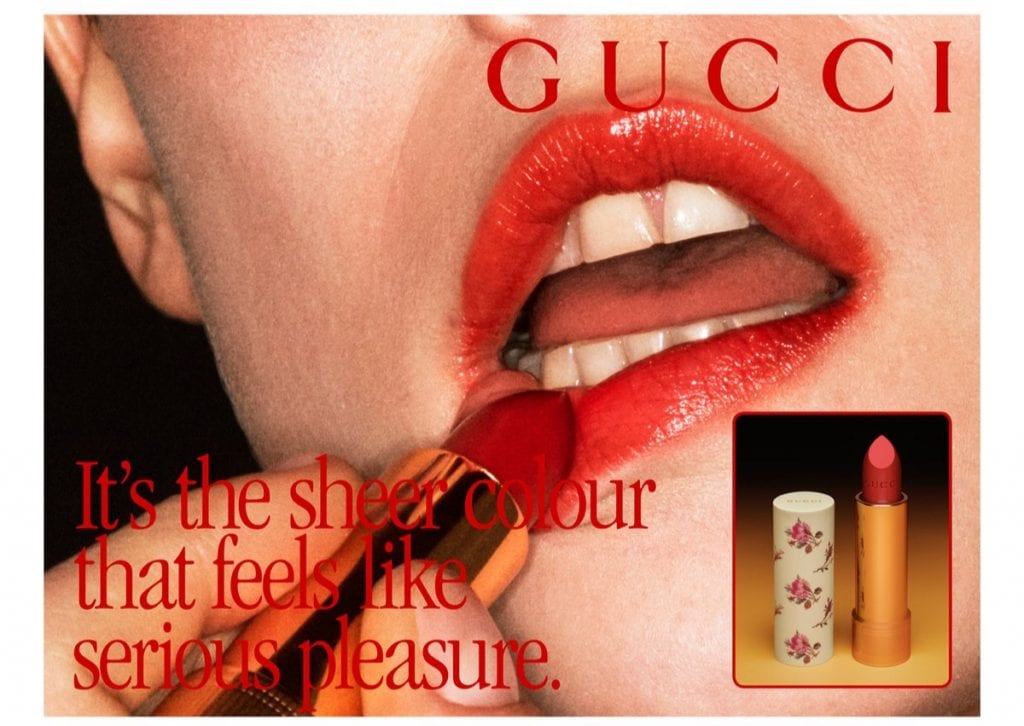

Take the Burberry, Coty deal: in April 2017, Coty announcedthat it would pay Burberry a whopping $225 million – plus an undisclosed sum of recurring royalties – for the right to use the British brand’s name on fragrances and cosmetics in the U.S. The heft of the revenue earned on the sale of such goods, minus the agreed-up royalty fees, will be recorded on Coty’s books, and the same goes for Gucci, Prada, Miu Miu, Calvin Klein, Marc Jacobs, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen, Tiffany & Co., and Jil Sander fragrances, for which Coty maintains the exclusive rights.

Due to the fixed duration of many of these licensing deals, fierce rivalry exists among the market’s most notable players each time an end-date approaches. That is how L’Oreal was able to poach the Valentino license from Puig (and before that, how Puig nabbed it from Proctor & Gamble), and how Euroitalia recently snagged Dsquared2 from fragrance licensor ICR, following a years-long partnership.

Licensed products, such as eyewear and fragrances, which are sold at much lower price points than a designer ready-to-wear, for instance, serve as a way for brands to court a large pool of consumers, including young shoppers, who brands can later convert into full-fledged luxury buyers, discretionary income permitting. Such deals also enable high fashion brands to expand into previously untapped categories, such as fragrances and beauty goods, which, as apparel and leather goods brands, they may not be equipped to explore in-house.

More than anything else, though, licensing deals serve as a noteworthy source of revenue for them. To put such deals into perspective: As of 2017, about 90 percent of the $160 million a year in sales at Calvin Klein Inc. comes from licensing the designer’s name to makers of underwear, jeans and perfume, making licensing an especially effective tool for fashion houses, especially those whose price points are traditionally too exorbitant for the average consumer.

In much the same way as the acquisitions of fashion brands by big-name conglomerates is head-line making material, so, too is the landing of fashion licensing deals and for good reason.