The Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) has ruled that Ferrari can retain the rights in its Testarossa trademark, even though production of the iconic sports car was discontinued in the 1990s. In a decision dated October 22, a panel of judges for the CJEU overturned a previous cancellation ruling, finding that the Italian automaker’s continued manufacture of vehicle parts for its Testarossa model fulfils the requirements for trademark use.

The closely-watched case dates back to 2017 when German toy manufacturer Autec challenged Ferrari’s Testarossa trademark in the German courts, arguing that Ferrari no longer fulfilled the obligation for trademark use, given that it had not manufactured the Testarossa car model for more than 20 years. Such inconsistent use is significant, as under European Union trademark law, a trademark registration is vulnerable to cancellation action if the holder of that trademark has not used it for a consecutive period of five or more years, which is precisely what was at play here, Aztec argued.

Autec pointed to two registrations that Ferrari held for the Testarossa brand name in Germany and Switzerland, both of which were revoked by the German court in connection with the toy company’s assertions. (Germany and Switzerland established an agreement in 1892 whereby use in one country counts as use in both countries.) Faced with a loss, Ferrari appealed against the decision to the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court, which referred the question of trademark use to the CJEU.

Parts, resale & the obligation of use

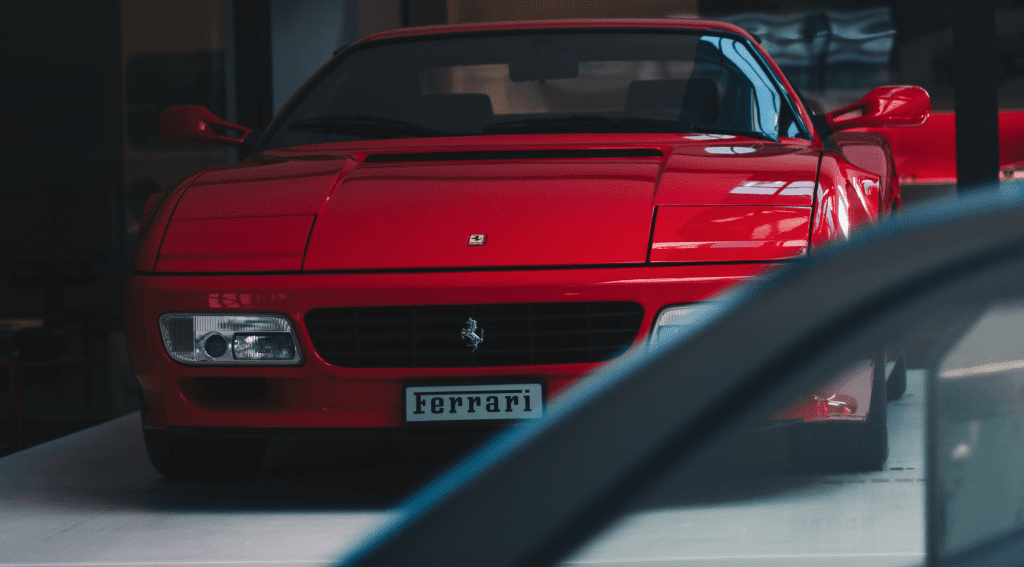

Ferrari sold a sports car model under the Testarossa name between 1984 and 1991, and released successive models (512 TR and F512 M) until 1996. Fast forward to 2014, and Ferrari produced a further copy with the Ferrari F12 TR model. In the period relevant to the assessment of trademark use, Ferrari also used the “Testarossa” trademark to designate some parts and accessories for the luxury sports cars that it had previously sold under that name.

In order for a trademark to be considered to be used consistently, that use does not always have to be extensive, especially when it comes to expensive sports cars that are usually only produced in small numbers. However, according to the German court, it was doubtful whether such information should be taken into account in the case of Testarossa, as the mark was not registered for luxury sports cars specifically, but for cars in general and parts thereof. The judge was of the opinion that, if it is necessary to verify whether the brands have been in genuine use on the mass market for cars and parts thereof, it must immediately be clear that this is not the case.

Likewise, the earlier court did not agree that the retail of second-hand vehicles bearing the Testarossa name constituted a new use of the mark since Ferrari’s trademark rights were exhausted after the products bearing those marks were placed on the market for the first time, and Ferrari cannot prohibit the resale of those products.

The CJEU perspective

In its ruling in October, the CJEU found that a trademark registered with respect to a category of goods and corresponding replacement parts must be regarded as having been put to “genuine use” in connection with all the goods in that category and the replacement parts thereof, even if it has been used only in respect of some of those goods. For example, “genuine use” could come from the manufacture/sale of high-priced luxury sports cars – or from the subsequent offer/sale of replacement parts or accessories for some of those goods. This applies unless it is apparent from the relevant facts and evidence that consumers wishing to purchase those goods will perceive them as an independent subcategory of the category of goods for which the mark concerned was registered.

The court also determined that a trademark is capable of being put to genuine use for the resale of second hand goods, so long as its owner “actually uses that mark, in accordance with its essential function which is to guarantee the identity of the origin of the goods for which it was registered, when reselling second-hand goods,” and that a trademark is put to genuine use where its owner provides certain services connected with the goods previously sold under that mark, on condition that those services are provided under that mark.

The CJEU preliminary ruling thereby overturned the 2017 ruling by the German court, and Ferrari is back in the battle to retain ownership of the Testarossa brand name.

Theo Visser is an IP Consultant at Novagraaf, an international patent and trademark consultancy that advises clients on intellectual property strategy and management.