In a first of its kind case, the highest court in Switzerland decided on the legality of the offering for sale and selling of customized watches without the authorization of the underlying brand – Rolex in this case. In a decision dated January 19, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court took on the issue of whether customization of luxury timepieces is permissible under Swiss trademark and unfair competition law, noting that this is the first time that it has been called upon to determine whether the unauthorized customization of a branded product at the request of the product’s owner runs afoul of the law.

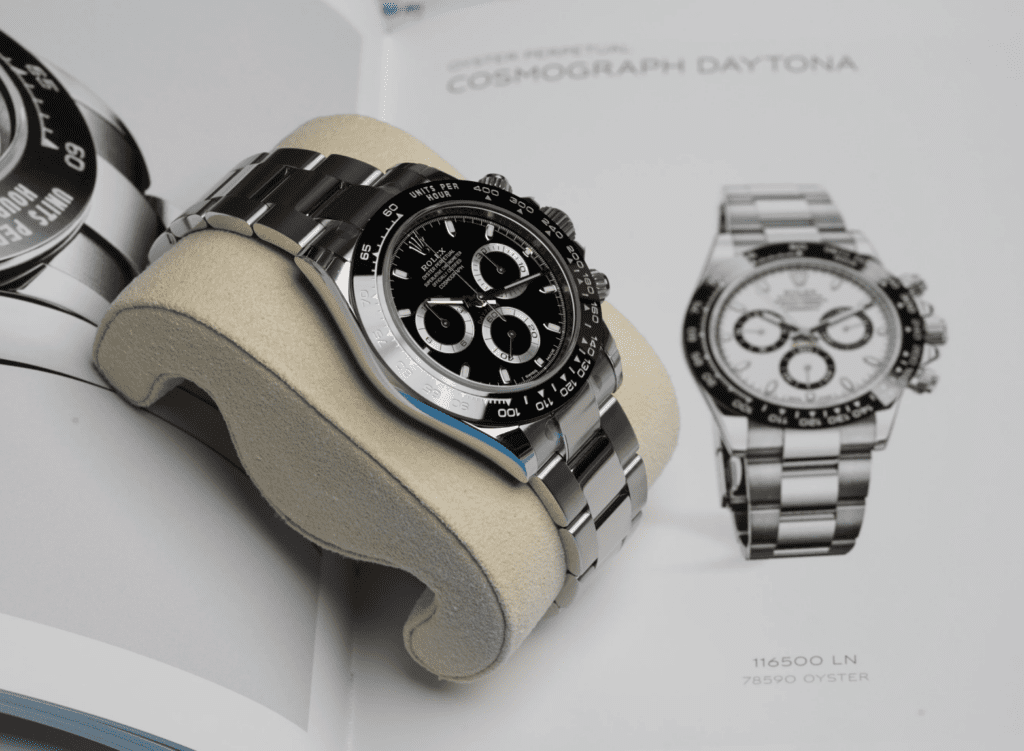

Some Background: Rolex filed suit against the defendant, an unnamed Geneva-based company in the business of “personaliz[ing] mass-produced luxury watches, mainly by Rolex, by changing certain parts, giving them a new appearance and/or modifying various technical characteristics in order to make them more exclusive in accordance with the wishes expressed by its customers.” In the complaint that it lodged with the Civil Chamber of the Court of Justice in December 2020, Rolex argued that the defendant was infringing its trademarks by offering up modified watches bearing its trademarks without authorization.

According to Rolex, the “customization” efforts carried out by the defendant sometimes require it to remove and then reapply trademarks that appear on the original Rolex watch dials. On modified models, the defendant routinely affixes its own trademark alongside those of the Rolex brand, per Rolex, and it offers consumers a new warranty, “specifying that the original [Rolex warranty] is automatically canceled following its intervention.”

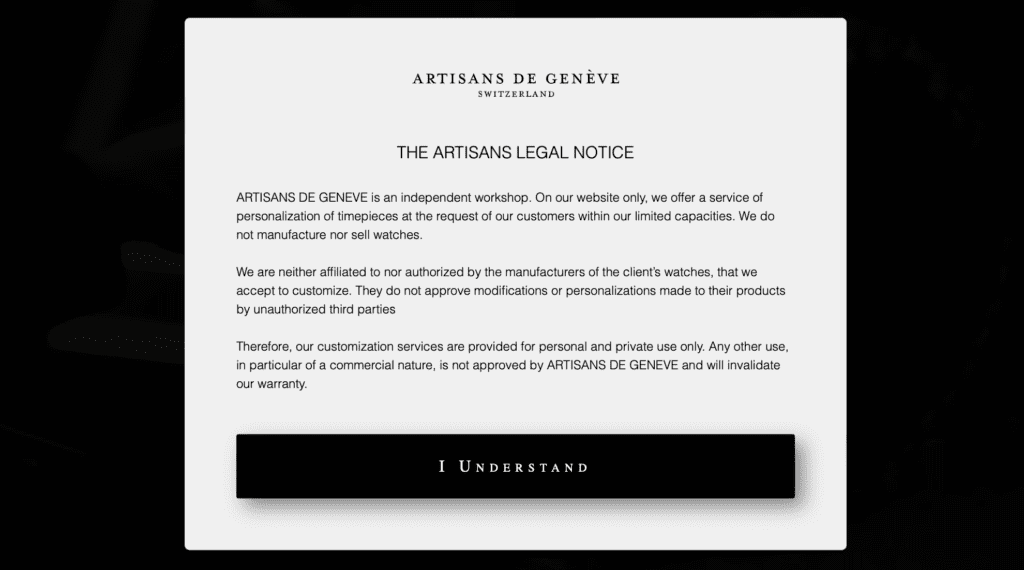

And in one more bit of background worth noting, the defendant does business via its e-commerce site, which requires consumers to acknowledge a disclaimer that states that it: (1) is an independent atelier offering watch customization services at the request of customers for private use; (2) does not manufacture or sell watches; and (3) is not affiliated with or authorized by any of the underlying watch manufacturers.

Before filing suit, Rolex notified the defendant of its infringement, prompting the defendant to limit its customization services to private clients, thereby, doing away with its practice of maintaining a stock of customized watches, which it marketed and resold to consumers via its website. (Note: A number of factors, including the workings of the new business model and the specific contents of the website disclaimer (see below), etc., make the defendant sound a lot like like upmarket Swiss watch workshop Artisans de Genève to me.)

The lower court sided with Rolex in February 2023 and granted injunctive relief to block the defendant from offering up the customized watches bearing Rolex’s trademarks. The defendant appealed the decision to the Swiss Federal Supreme Court shortly thereafter.

Customization Before the Supreme Court

Setting the stage in its decision, the Supreme Court stated that trademark exhaustion exists under Swiss trademark law, thereby, enabling the purchaser of a trademark-bearing product to resell that product after it has been released into the market by the trademark holder without facing trademark liability. Moreover, the court noted that it has previously held that save for some statutory exceptions, the use of a trademark for private purposes (and not the average “the course of business“) is not prohibited, as it will not give rise to a likelihood of consumer confusion.

At the same time, the Supreme court stated that the lower court’s judgment demonstrates a “profound misunderstanding of the difference between two distinct commercial activities,” namely watch personalization services and the marketing of modified watches …

> Customization at the request of the product owner: The Supreme Court held that the first type of activity consists of a company personalizing a branded object at the request and on behalf of its owner for personal use. This is “in principle lawful, to the extent that the service provider acts at the request of the owner of the object concerned and where the customized item is returned to its beneficiary … [and not] (re)placed on the market,” according to the court. The court’s reasoning here: “When it personalizes a branded item at the request of its owner, the company concerned is not … using the brand of a third party on the market to offer its own services, but is only modifying an item for specific, private purposes.”

> The commercial marketing/offering for sale of customized products: A second type of activity consists of the broader marketing of modified watches that still bear the branding of the underlying company (Rolex in this case). “In the absence of authorization granted by the owner of the said brand, such activity in principle contravenes the Law on the Protection of Trademarks,” the court held. In such a case, “the mark is, in fact, used on the market and no longer fulfills its identifying function because it no longer designates the original article, which has undergone modifications without the consent of the [trademark] owner.”

In the case at hand … the court stated that Rolex was able to acquire a customized Daytona watch from the defendant in February 2020 for 32,580 francs (roughly $36,900 at the time). This example falls within the realm of the second category of activities, and thus, is “contrary to the law.”

Reflecting on the defendant’s newer operations model, which sees it exclusively modify the watches already-owned by clients, the court held that this may require the defendant to “remove and re-apply” Rolex’s trademarks on the watches that it personalizes and to include its own marks next to the Rolex marks. However, as distinct from the former example, “such interventions take place within the company, at the request of the owner of the property concerned and, once its work has been carried out, the [defendant] returns the personalized watch to its owner for personal use, without the watch having been (re)placed on the market,” the court held.

As such, this “does not infringe the right of exclusive use” of the holder of the trademark(s) concerned.

In terms of Rolex’s claims under the Swiss Federal Law Against Unfair Competition, the court sided with the defendant, holding that its customization of clients’ watches “does not, in itself, contravene the [law], since the act of unfair competition must be objectively capable of influencing the market.” Since the defendant no longer places the watches back on the market after they have been modified, it does not breach the tenets of the Federal Law Against Unfair Competition, according to the court.

Not finished, the court turned its attention to whether the defendant is running afoul of trademark and/or unfair competition law by way of its marketing of its customization services. On this front, the agreed with Rolex, finding that the defendant’s advertising of modified watches that include Rolex’s trademarks alongside its own name is likely to cause consumers to erroneously believe that the watches are the result of a collaboration between the two parties. The defendant made a nominative fair use-centric argument on appeal, asserting that it only uses Rolex’s trademarks “in a purely factual manner” in its marketing, namely, to “illustrate the way in which [it] personalizes certain models that display said trademarks.”

Remanding the issue back to the Civil Chamber, the Supreme Court found that the lower court based “a large part of its reasoning on the erroneous premise according to which the appellant’s commercial activity was illicit, which is why it could not refer to the [Rolex’s] trademarks to offer its services.” As such, “even though [the lower court] emphasized that the use of others’ trademarks could prove necessary for a service provider to inform its potential customers about its own activities” (and in fact, “everyone can use indications to describe their own offers of products or services, even if they affect the brands of third parties”), it carried out an “incomplete analysis of the situation both on a factual level and on a legal level from the angle of trademark law.”

TLDR: The defendant’s current business model “appears neither contrary to trademark law nor incompatible with the rules of the Federal Law Against Unfair Competition.” And in terms of the legality of its advertising of its customization services (both from a trademark and unfair competition perspective), the lower court must reconsider the issue in light of the relevant facts at play.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: The court did some of the work for us when it comes to the broader relevance of the matter, stating that the question at the heart of this case “is far from trivial in practice, since the activity of customizing branded objects is booming and this is not limited to the watchmaking field, but also concerns many other sectors, including fashion and automobiles.”

The “growing importance” of the customization/personalization of trademark-bearing items is “also reflected in the emergence of new conflicts dividing brand owners from companies modifying goods bearing the original brand of third parties,” the Supreme Court stated. It noted that it is, therefore, “no coincidence that the judicial authorities of the countries around us … have had to resolve various problems in relation to this theme and have thus rendered several decisions likely to present a certain interest.”

Pointing to previously-decided customization-centric cases, the court specifically referred to a 1992 matter involving the resale of modified Levi’s jeans and a more recent decision from the Landgericht of Hamburg, which held that a German company’s sale of personalized models of watches bearing Rolex’s trademark brand violated trademark law and that the principle of exhaustion did not apply given the modifications made to the said watches.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit recently sounded off on the advertising and sale of modified watches, holding that a third-party reseller was engaging in trademark infringement by selling watches that contained both Rolex and non-Rolex parts, and marketing them as “Genuine Rolex” goods – albeit without including sufficient disclosures about the nature of watches, thereby, creating a likelihood of consumer confusion.

The case is Rolex SA v. A. _______ SA, 4A_171/2023 (Tribunal fédéral).