In a recent decision, Barcelona’s Ninth Mercantile Court sided with Mango in a lawsuit waged against it by the Spanish copyright society, VEGAP, over the creation of non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) based on the works of three well-known Catalan artists, finding that the Spanish fast fashion retailer could rely on available defenses, including the doctrine of harmless use.

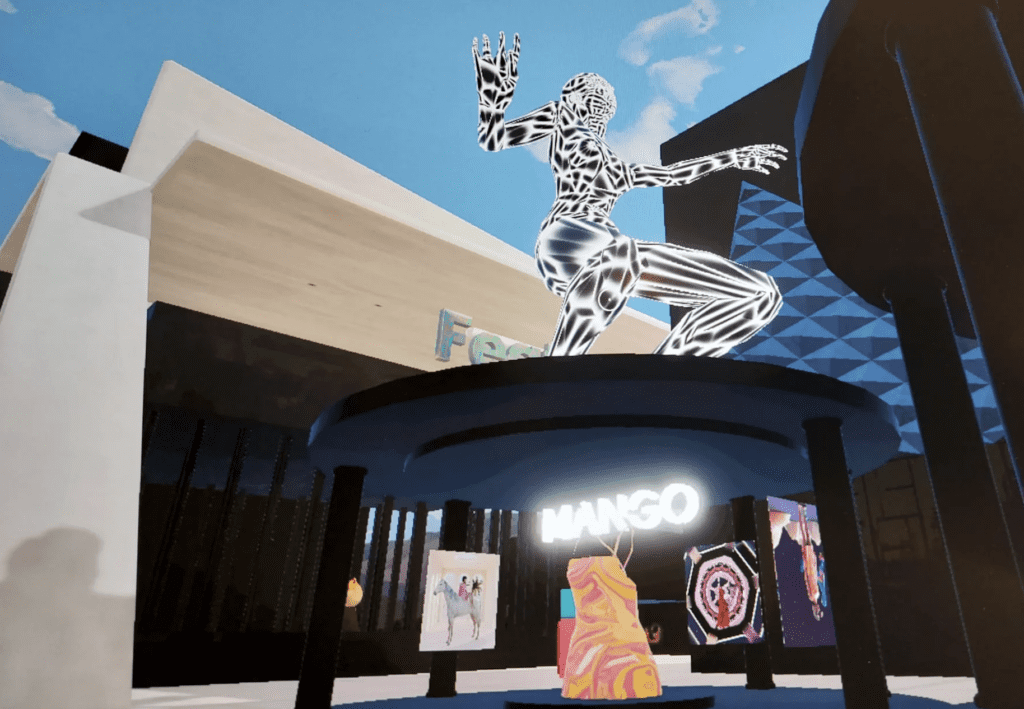

Background: As previously reported by IPKat, VEGAP, a collective management organization for intellectual property rights in Spain, brought a claim against Punto Na SA, the intellectual property holding company for Mango, seeking compensation for the alleged infringement of copyright in certain artworks. According toVEGAP, in connection with the opening of a new store in New York, Mango had commissioned the creation of a collection of NFTs based on digital copies of works of famous artists, such as Miró, Tàpies and Barceló (of which Mango owned the physical originals), incorporating various outfits of the collection available at the store, to be displayed in the Decentraland metaverse platform.

During the opening of the store, the works were simultaneously exhibited in three distinct ‘

“dimensions” … physical (in the physical store, itself), digital (on the Opensea platform), and virtual (on the Decentraland metaverse platform).

At the heart of VEGAP’s case were three key issues: (1) Whether the right of public exhibition enjoyed by the owners of physical artworks extended to exhibition of digital versions online; (2) Whether the digitization of physical paintings and storage online required the consent of the authors or rightsholders in such paintings; and (3) Whether the relevant works had been transformed by their conversion into digital form, including by the inclusion of new elements, such that the rights of adaptation (under Spanish law) and communication to the public were engaged.

It is worth noting that the NFTs in question were “lazy minted,” meaning that they were not actually on the blockchain, such that they could not be transferred to the wallets of any third parties (or even the cold wallet of any entity within the Mango group).

The Court’s Ruling

In its January 11 decision, the Court began by examining the moral right of dissemination and the right of communication to the public …

Moral Rights: In accordance with Spanish law and seeing as the relevant artworks had already been displayed to the public at large, the court found that any moral rights st issue had been exhausted, and there was no further infringement.

Communication to the public: As for the right of communication to the public, the Court observed that there clearly was a new communication here in light of the breadth of people to whom the works could be shown online, thereby, requiring Mango was get the authorization of the works’ authors or the owners of the copyright therein. However, there was no evidence that the right to public exhibition of the works had been expressly carved out from the contractual arrangements governing the sale of the physical artworks to Mango, and the Court considered that Mango (as the new owner) was accordingly entitled to display the works publicly in any environment of its choosing, whether physical or virtual.

Further, the Court found that there had been no damage to the reputation of the authors of the works, as the original works had been exhibited at the same time as their digital counterparts, with attribution to their respective authors.

Adaptation: The main crux of the Court’s judgment revolved around whether the digitization of the works constituted an adaptation that requires the consent of the authors/rightsholders. The Court went to some length here discussing the doctrine of harmless use, despite the fact that such a doctrine does not actually exist in Spanish statutory law. The Court referred to a 2012 decision of the Spanish Supreme Court in the Google case (Sentencia no. 172/2012) in which the Supreme Court effectively created an ad hoc doctrine of harmless use in Spanish law, including by referencing the Berne three-step test.

And somewhat curiously, including the four fair use factors set out in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act, namely: (1) The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the work protected by copyright; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Applying the same four factors, the Court found that in this case …

> The use of the works by Mango was non-commercial, as it was merely for the purpose of exhibiting the works to commemorate the opening of the New York store, and the retailer did not obtain any compensation from such exhibition. Moreover, there was not any evidence that sales of Mango products increased as a result of the use of such artworks. Further, whereas the physical works may initially have been created for commercial (albeit creative) purposes, the Court considered that their digital/virtual counterparts had been created for purely secondary reasons.

> As for the nature of the work, the Court observed that although the physical works had been used to create new, digital works, the new works respected the spirit of the originals and gave their authors proper attribution and recognition.

> Although the entirety of the original works had been copied through their digitization, the Court observed that there were precedential cases in which the use of a complete work was considered legitimate.

> Given that the new digital works were not being marketed or offered for sale, the Court found that they did not interfere with or cause any damage to the value of the original physical works.

With the foregoing in mind, the Court held that the digitization of the physical works by Mango constituted “harmless use” such that the authorization of the copyright rights holders in the original works was not required.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: This decision is an interesting early insight how courts might approach cases involving intellectual property rights in virtual/digital scenarios, and it is particularly striking given the application of a fair use-like exception where no such exception exists in Spain’s statutory copyright laws. It may be the case that national courts will increasingly borrow from other jurisdictions’ jurisprudence in the realm of IP if they feel that their own is not suited to a specific virtual or novel use which would not have been accounted for by the legislators, and it is encouraging to see courts apply that sort of flexibility.

It seems that in this case, having decided that Mango did have the right to exhibit the physical works in public, the Court then worked to find a way of accommodating its virtual equivalent.

Alessandro Cerri is in-house legal counsel on the global IP team of Warner Bros. Discovery, based in the UK. (This article was initially published by IPKat).