One of the newest cases to bring companies’ sustainability-centric claims under the microscope is a proposed class action lawsuit waged against Sephora over a collection of “clean” cosmetics. According to the complaint that she filed in a New York federal court in November, Plaintiff Lindsey Finster claims that by “manufactur[ing], label[ing], market[ing], certify[ing] and/or sell[ing] cosmetics advertised as ‘Clean’ – when no shortage of the products contain ingredients that are “inconsistent with how consumers understand” the term “clean,” the beauty retailer is engaging in false advertising and breaching warranties that it has made to consumers in connection with those products.

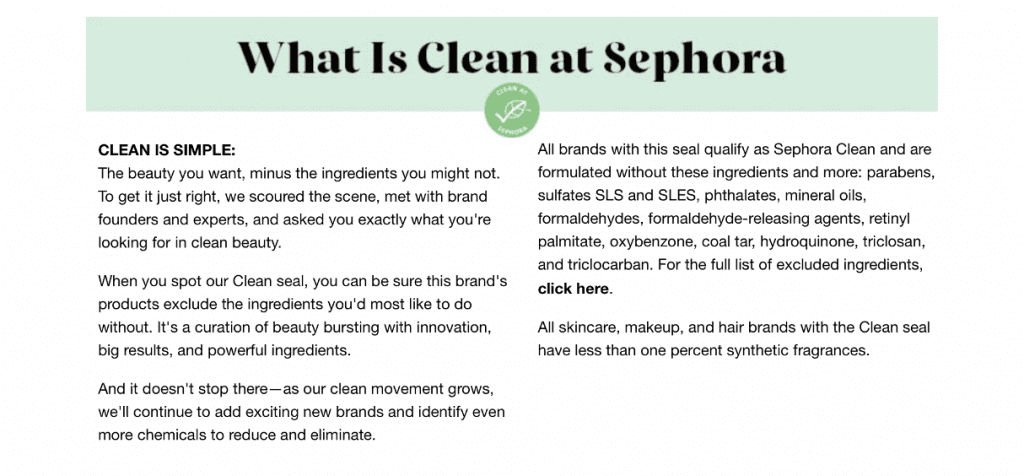

In the complaint, Finster asserts that in furtherance of its “Clean At Sephora” initiative, Sephora advertises “select products” that it has “evaluated to provide ‘The beauty you want, minus the ingredients you might not. This seal means formulated without parabens, sulfates SLS and SLES, phthalates, mineral oils, formaldehyde, and more.’” According to Sephora, when products meet this criteria, they are promoted with the green “Clean At Sephora” seal (complete with a green checkmark and leaf symbol) in Sephora stores and online, which means that “consumers … can be assured that the product is formulated without specific ingredients that are known or suspected to be potentially harmful to human health and/or the environment.”

Against this background, Finster alleges in the lawsuit that she “saw and relied on the ‘Clean at Sephora’ seal,” which led her to believe that the cosmetics products’ ingredients “were not synthetic nor connected to causing physical harm and irritation.”

The problem, Finster argues, is that “a significant percentage of products with the ‘Clean At Sephora’ [label] contain ingredients inconsistent with how consumers understand this term.” For instance, Finster points to the Sephora-stocked Saie Mascara 101 that she says, “contains numerous synthetic ingredients” – such as polyglyceryl-6 distearate, polyglyceryl-10 myristate, cetyl alcohol, phenethyl alcohol, and sodium benzoate – “several of which have been reported to cause possible harms.”

Sephora “makes other representations and omissions” with respect to the “Clean at Sephora” products, per Finster, and as a result, is able to offer up these goods at prices that are “higher than similar products [that are] represented in a non-misleading way, and higher than they would be sold for absent the misleading representations and omissions.” Finster, for one, says that she has been damaged (and has standing to sue), as she would not have paid more for the products or purchased them at all “had she known the ‘clean’ representations were false and misleading.”

With the foregoing in mind, she contends that Sephora is running afoul of New York General Business Law sections 349 and 350, which prohibit deceptive acts or practices in the conduct of business, and false advertising, in particular; violating state consumer fraud acts; and engaging in beaches of express warranty, implied warranty of merchantability/fitness for a particular purpose and the Magnuson Moss Warranty Act.

In terms of the warranties made by Sephora here, Finster alleges that the LVMH-owned retailer warranted that the ingredients in the “Clean At Sephora” products are “not synthetic nor connected to causing physical harm and irritation.” Sephora did not expressly make these claims; according to the complaint (and the language on Sephora’s website), Sephora defines its “Clean” seal as referring to products that are “formulated without parabens, sulfates SLS and SLES, phthalates, mineral oils, formaldehyde, and more.”

Nonetheless, Finster maintains that regardless of how Sephora defines “Clean,” consumers understand it as being “consistent with its dictionary definitions, which define it as describing something free from impurities, or unnecessary and harmful components, and pure.” In the context of “cosmetics,” she asserts that “this means products made without synthetic chemicals and ingredients that could harm the body, skin or environment.” As such, Finster holds Sephora to that definition, arguing that it “warranted that its ingredients were not synthetic nor connected to causing physical harm and irritation.”

As for the strength of Finster’s argument here, it is worth noting that “clean” is not unlike “sustainable,” “eco,” “green,” etc., which also lack clear definitions (and guidance from entities like the Federal Trade Commission, whose Green Guides provide guidance on environmental marketing claims), and thus, are routinely used/marketed in different ways by different companies. This is a symptom of how in the “regulatory vacuum” that is the cosmetics industry, “companies have developed their own standards and terms purporting to inform consumers about the attributes of their products,” per Finster.

It is unclear how the court will treat Finster’s claims. There may be room for Sephora to push back against her assertions on the basis that “clean” is not a readily measurable term and that, as studies have shown, consumers do not apply a single definition to these terms or really know what they mean. Moreover, given that Sephora lists the chemicals/compounds that are specifically excluded from the products that fall under the umbrella of the “Clean At Sephora” initiative, it seems somewhat safe to assume that as long as the products do not include those things, it has not engaged in false and/or otherwise deceptive advertising. Although, it will be interesting to see how the court handles Finster’s allegations that consumers understand “clean” to mean something else.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: While the number of sustainability-centric advertising lawsuits has been on the rise, including in the fashion and cosmetics segments, these cases are not necessarily proving to be easy wins for the plaintiffs. In fact, courts have been shutting down at least some of these suits over sustainability marketing claims with some frequency. As recently as November, for instance, a Superior Court in Washington, D.C. determined that Coca-Cola’s marketing of itself as “a sustainable and environmentally friendly company” (despite being “one of the largest contributors of plastic pollution in the world,” according to the plaintiff) was not actionable, as its claims were aspirational in nature. This highlights the fact that “environmental aspirational claims – even those tied to specific measurement attributes – are not necessarily sufficient to state a claim.”

Allbirds similarly escaped a false advertising lawsuit last year, with a judge for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York finding that the plaintiff’s issue was actually with the HIGG standard, which Allbirds used to measuring environmental impact of its products and not how the footwear company advertised its products in accordance with that data.

Meanwhile, Rawson v. Aldi, a proposed class action over the marketing of “sustainable” seafood, went the other way this summer, with a federal court in Illinois refusing to dismiss the complaint on the basis that Plaintiff Jessica Rawson sufficiently pled her false advertising, breach of state consumer protection statute, and breach of express warranty claims. Reflecting on the court’s determination, Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz’s Jeff Greenbaum cautioned marketers, stating that “while there may not be a lot of specific guidance out there right now about how to make ‘sustainability’ claims,” there is still “a good chance that a court or a regulator will see a ‘sustainability’ claim as communicating a general claim about the environmental benefits provided by the product,” which means that companies should not “just assume that the statement is puffery and that no substantiation is required.”

Greenbaum also stated that in order to help avoid allegations that you are overstating the environmentally beneficial attributes of the product, it is “best to be specific about what benefits are being provided” (which Sephora arguably did here by listing the excluded chemicals). Ideally, companies will “explain the benefit(s), and avoid [making] general environmental benefit claims altogether.” However, he contends that “if you are going to claim that a product is ‘sustainable,’ it is best to qualify the statement with a clear explanation of why it is sustainable.”

The case is Finster v. Sephora USA Inc., 6:22-cv-01187 (N.D.N.Y.)