A massive force is reshaping the fashion industry: secondhand clothing. According to a new report, the U.S. secondhand clothing market is projected to more than triple in value in the next 10 years – from $28 billion in 2019 to $80 billion in 2029 – as part of the larger apparel market in the U.S., which is currently worth $379 billion, and as of last year, sales of secondhand clothing expanded 21 times faster than conventional apparel retail did, shedding light on the power of this burgeoning segment of the market.

Even more transformative is secondhand clothing’s potential to dramatically alter the prominence of fast fashion. A business model characterized by cheap and disposable clothing that emerged in the early 2000s, epitomized by brands like H&M and Zara, fast fashion grew exponentially over the next two decades, significantly altering the fashion landscape by producing more clothing, distributing it faster and encouraging consumers to buy in excess with low prices. While fast fashion is expected to continue to grow 20 percent in the next 10 years, secondhand fashion is poised to grow 185 percent. With this in mind, the widespread adoption of secondhand clothing has the potential to reshape the fashion industry and mitigate the industry’s detrimental environmental impact on the planet.

The next big thing

The secondhand clothing market is composed of two major categories, thrift stores and resale platforms. But it is the latter that has largely fueled the recent boom. Secondhand clothing has long been perceived as less fashionable that its new-clothing-counterpart, and mainly sought by bargain hunters. However, this perception has changed, and now many consumers consider secondhand clothing to be of identical or even superior quality to unworn clothing. Indicative of this: the trend of “fashion flipping” – or buying secondhand clothes and reselling them – has also emerged, particularly among young consumers.

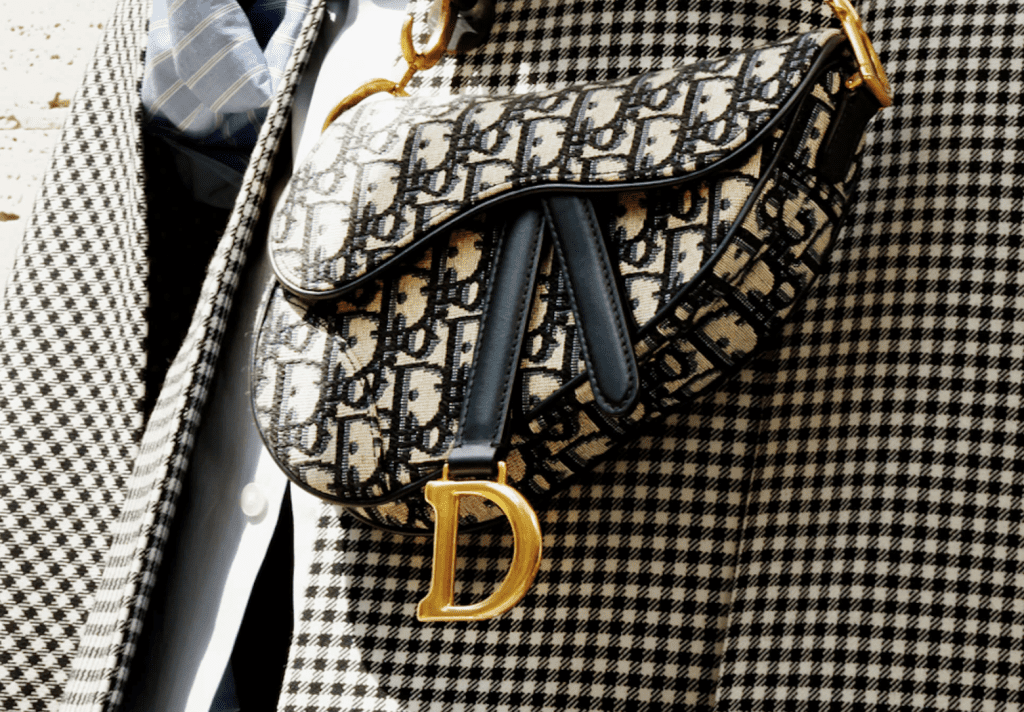

Thanks to growing consumer demand and new digital platforms like Tradesy and Poshmark that facilitate peer-to-peer exchange of everyday clothing, the digital resale market is quickly becoming the next big thing in the fashion industry. At the same time, the market for secondhand luxury goods is also substantial. Retailers like The RealReal and Vestiaire Collective provide a digital marketplace for authenticated luxury consignment, where can people buy and sell designer labels, such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel, and Hermès, helping the market value of this sector toreach $2 billion in 2019.

In addition to changing perceptions and the ease now associated with browsing and shopping second hand, the push towards widespread adoption also appears to be driven by affordability, especially now, during the COVID-19 economic crisis. Consumers have not only reduced their consumption of nonessential items like clothing, but are buying more quality garments over cheap, disposable attire. For clothing resellers, the ongoing economic contraction combined with the increased interest in sustainability has proven to be a winning combination.

More mindful consumers?

The fashion industry has long been associated with social and environmental problems, ranging from poor treatment of garment workers to pollution and waste generated by clothing production. Less than 1 percent of materials used to make clothing are currently recycled to make new clothing, a $500 billion annual loss for the fashion industry. The textile industry is responsible for a staggering amount of carbon emissions, and approximately 20 percent of water pollution across the globe is the result of wastewater from the production and finishing of textiles.

Consumers have become more aware of the ecological impact of apparel production and are more frequently demanding apparel businesses expand their commitment to sustainability. Buying secondhand clothing could provide consumers a way to push back against the environmentally-taxing nature of the fast-fashion system. Beyond that, buying secondhand clothing increases the number of owners an item will have, thereby, extending its life – something that has been dramatically shortened in the age of fast fashion. (Worldwide, in the past 15 years, the average number of times a garment is worn before it is discarded has decreased by 36 percent.)

High-quality clothing traded in the secondhand marketplace also retains its value over time, unlike cheaper fast-fashion products. As such, buying a high-quality secondhand garment instead of a new one is theoretically an environmental win. But some critics argue the secondhand marketplace actually encourages excess consumption by expanding access to cheap clothing.

Our latest research supports this possibility. We interviewed young American women who regularly use digital platforms like Poshmark. They see secondhand clothing as a way to access both cheap goods and ones they ordinarily could not afford. They do not see it as an alternative model of consumption or as a way to decrease dependence on new clothing production. [TFL note: The production of new clothing at the same rate and volume as clothing is currently being manufactured and distributed – even if that new clothing is “sustainably-made,” “green,” “eco-friendly,” etc. – is a critical and often over-looked element in the discussion of/push towards sustainability and unless addressed, stands in the way of achieving a real model of sustainability].

Whatever the consumer motive, increasing the reuse of clothing is a big step toward a new normal in the fashion industry, one that has long thrived on constantly pushing novelty in order to sell more, though its potential to address sustainability woes remains to be seen.

Hyejune Park is an Assistant Professor of Fashion Merchandising at Oklahoma State University. Cosette Marie Joyner Armstrong is an Associate Professor of Fashion Merchandising at Oklahoma State University.