In 2021, Bulgari SpA discovered that the domain bulgarireplica.it – which was registered by an unaffiliated individual named Gaetano Pierro – was being used to host a website offering up identical copies of some of its famed designs. Having pin-pointed the counterfeit-selling operation, counsel for LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton-owned Bulgari initiated a domain name re-assignment proceeding with Italy’s Domain Dispute Resolution Center (“CRDD”) on the basis that it is the rightful owner of the Bulgari trademark, and that such unauthorized use of the Bulgari name to offer up infringing goods runs afoul of its rights in that mark, one that the brand argued that it has been using since its founding in 1884 and which “has been known internationally since the 1970s.”

According to a subsequently issued decision in favor of Bulgari S.p.A, a representative for the CRDD held that “it appears that the domain name bulgarireplica.it was used to attract users by exploiting the reputation of the BULGARI brand and diverting its potential customers” away from the brand by way of “copies of the same commercial products of the trademark owner.” There is “no doubt about” Bulgari’s right to the exclusive use of the Bulgari name, the CRDD panelist asserted, as “the Bulgari brand has been used by [Bulgari S.p.A] for over a century,” “the name Bulgari corresponds exactly to the company name Bulgari S.p.A. with consequent right to the name [being held] by the applicant company,” and Bulgari S.p.A maintains valid trademark rights in the “Bulgari” name, which has been registered in “many countries for various commercial classes by Bulgari S.p.A. and its affiliated, controlled and associated companies.”

In addition to making use of a domain that explicitly included the Bulgari name, the website was offering up “products that exactly replicate the products of the famous [Bulgari] brand,” which Bulgari argued – and the CRDD agreed – was likely to confuse consumers, thereby, prompting the CRDD to side with Bulgari in terms of which party should assume ownership of the domain.

Turning its attention to the use of “replica” in the domain name, the CRDD determined that the use of the word was “the only difference” between Bulgari’s domains and the allegedly infringing bulgarireplica.it domain, and it served as “a clear explanation that it is, precisely, a copy and not the original.” This “does not lead us to believe that [Mr. Pierro] is using the Bulgari name on the basis of his own right, but that he is simply exploiting the reputation of the Bulgari brand for the online sale of objects that are copies of Bulgari jewelry,” the CRDD asserted in its decision. “This makes it possible to exclude the circumstance that [Pierro] is making a legitimate non-commercial or commercial use without the intent of misleading [Bulgari’s] customers or infringing the registered trademark.”

The CRDD ultimately found that Pierro – who did not respond to or participate in the proceedings at all – “lacked any title or right to the domain name in dispute,” and that his “registration and use of the domain [was done] in bad faith.” As such, ownership of the domain was assigned to Bulgari.

Replicas and Dupes

The relatively straightforward Bulgari matter is an interesting one in large part because of the use of “replica” in the domain. While “the legal definition of ‘counterfeit’ does not apply to all ‘replicas,’” according to IP Twins’ Emmanuel Gillet, as counterfeiting carries a higher bar than infringements or mere replications, “experience has, nonetheless, shown that using the word ‘replica’ in the digital environment is often aimed at consumers who are searching for counterfeit goods.”

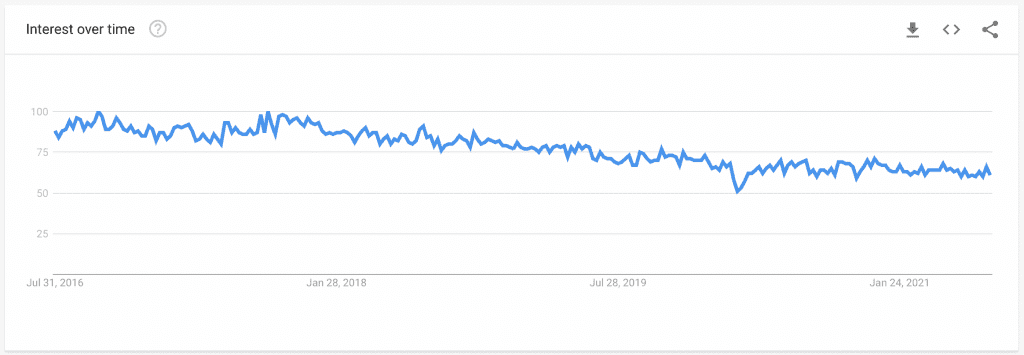

While recent Google Trends data indicates that searches for the word “replica” are steadily declining overall, Gillet notes that this case – paired with the fact that “searches for the word ‘replica’ remain frequently associated with specific products, namely, watches and handbags, as well as luxury brands, such as Louis Vuitton, Rolex, and Gucci,” among others – indicates that “it is too early for brand owners to lower their guard” when it comes to policing such uses.

Additional data reveals strong interest among consumers in certain geographies, in particular, when it comes to seeking out fakes by searching for “replicas,” per Gillet, who says that “Italian Internet users have shown strong search-specific interest in the word ‘replica,’” followed only by searches by consumers in Romania. Puerto Rico, Australia, and the United Kingdom took the number 3, 4 and 5 spots.

As such, Gillet states that “it is crucial for Bulgari” – and other brands – “to monitor the use of its brand in the digital space and initiate legal proceedings to put an end to any form of illegal use” of its name and other trademarks. Finally, “Composing a domain name that reproduces a famous trademark along with to words, such as ‘replica’ or ‘fake’ remains frequent.” Gillet points to proceedings before the World Intellectual Property Organization over domains, such as replicahermes.com, goyardreplicaus.com, replicahandbagshermes.com, cartier-replica.com, and faketagheuer.com, among others, as further proof of the “phenomenon,” and further evidence that bulgarireplica.it is “only one” of a larger pattern of bad actors that brands need to continue to pay attention to.

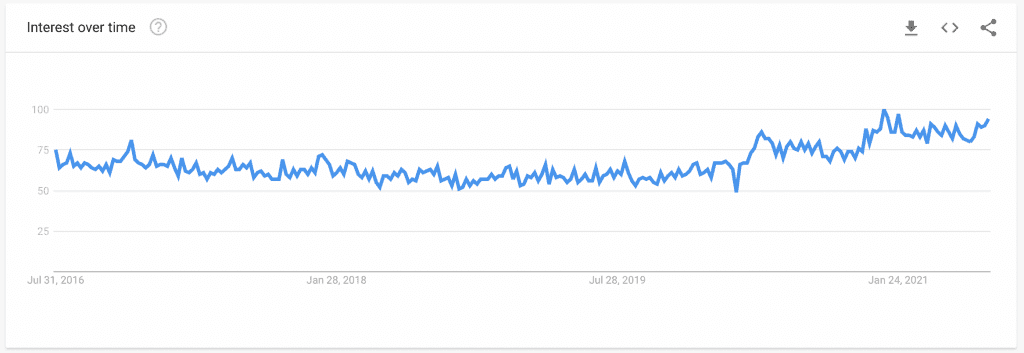

Also worthy of brands’ attention are searches for “dupes,” which have been on the rise in recent years, likely as a result of the fact that younger users on TikTok, as well as other social media platforms, have adopted the term to refer to products, such as copycat luxury and fashion goods, even spawning an entire genre of influencers, coined, “dupe influencers,” as Amazon highlighted in the lawsuit that it filed in November 2020 against a number of influencers and sellers on its third-party marketplace.

Interestingly, the use of the term “dupe” in this context is almost always inaccurate, as the items are not actually “dupes,” a term that it traditionally used to refer to legally above-board products that take inspiration from other, existing (and often much more expensive) products, from fast fashion garments to buzzy makeup and skincare products. Instead, the new use of “dupe” refers to products that make unauthorized use of brands’ names and other legally-protected trademarks, meaning that they are not “dupe,” but trademark infringing and/or counterfeit goods.

The use of the term dupe in this way comes as part of a larger trend of young consumers seeking out and purchasing counterfeit goods. As TFL previously reported, a 2019 study from the International Trademark Association (“INTA”), which polled 1250 American consumers between the ages of 18 and 23, found that 71 perfect of Gen Z-ers in the U.S. had purchased a counterfeit good over the past year, with apparel and footwear being among the most-purchased types of fakes.