In 2014, Apple, Google, Intel, and Adobe agreed to quietly settle a high-stakes, closely-watched lawsuit. The case – which was filed on behalf of nearly 65,000 individuals, seeking some $3 billion in damages – had progressed through the pre-trial stage before a federal court in San Jose, California, and in the process, strongly-worded emails signed by late Apple founder Steve Jobs and Google co-founder Sergey Brin, among other top execs, emerged as key evidence of the tech titans allegedly working together, between 2005 and 2009, to drive down the wages of employees by agreeing to avoid hiring each other’s workers. The so-called “no poaching” pact, the plaintiffs argued, ran afoul of a more than 100-year old federal statute that outlaws such restraints of trade.

The terms of the settlement remain confidential: although, the four defendants reportedly paid out $325 million on the basis that they not admit any wrongdoing. As Intel’s Chuck Mulloy told the Wall Street Journal in light of the settlement in April 2014, “We still deny violating any laws or obligations to plaintiffs.” The general consensus about the settlement in the civil lawsuit – which coincided with a 2010 Justice Department-initiated case – was that the tech behemoths were tired of having the communications of their upper-most figures splashed about in court.

“Emails between the executives made compelling reading in Silicon Valley and embarrassed the executives and their companies,” the WSJ’s Jeff Elder wrote at the time. The settlement provided reprise from that, and shielded them – i.e., the very powers that be at the likes of Apple, Google, Intel, and Adobe – from having to face a jury of their peers and the increasingly-intense media fury that would inevitably come with that.

The official response from the tech co.’s camps, if they opted to comment at all (Apple and Google said nothing), mostly came in the form of some boilerplate statement along the lines of, “We chose to settle this matter in order to avoid the uncertainties, cost and distraction of litigation.”

Six years after that case was put to bed, some of the players at the tippy-top of the upper echelon of high fashion have been served with the industry’s own version of the matter, one that sees Louis Vuitton (the largest luxury goods brand in the world), Fendi, Loro Piana, Gucci, Prada, Brunello Cucinelli, and Saks Fifth Avenue accused of engaging in an “illegal conspiracy” to “suppress the total compensation of their employees.” That is what three former Saks Fifth Avenue employees assert in a proposed class action lawsuit that similarly cites violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act, a federal statute that dates back to 1890 and prohibits activities that restrict interstate commerce and competition in the marketplace.

The crux of the newly-filed case? The defendants allegedly entered into “unlawful No-Hire Agreements” in order to control the wages and certain job conditions of luxury retail employees.

According to the complaint that Susan Giordano, Angelene Hayes, and Ying-Liang Wang, filed in a federal court in Brooklyn, New York last week, Saks and an array of brands that operate in-store leases with the department store – namely, Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Loro Piana, Gucci, Prada, and Brunello Cucinelli (the “Leased Entities”) – abide by ongoing deals amongst themselves. The three plaintiffs, who were previously employed as Luxury Retail Employees at Saks, claim that if a Saks Luxury Retail Employee were to seek employment with one of the luxury brands, the brand would require that the employee “resign from Saks and wait six months before [it would] be allowed to hire the Luxury Retail Employee.”

(Based on the in plaintiffs’ complaint, it appears as though they are alleging that the conditions/implications of the alleged “no poach” pacts on Saks employees are not made clear to employees at the outset and the mandated six month “rest” period between jobs is not compensated in the way that an employee would be paid during the duration of a non-compete period, for example).

As a result of these alleged agreements between Saks and the Leased Entities, Giordano, Hayes, and Wang claim that they were prevented from advancing in their careers. Ms. Hayes, for instance, alleges that while she was employed as “a Sales Consultant at a Saks Fifth Avenue store” in Ohio, she “was unable to seek and obtain employment at Saks’s competitor, Louis Vuitton, where she would have benefited from greater compensation and opportunities for upward mobility.”

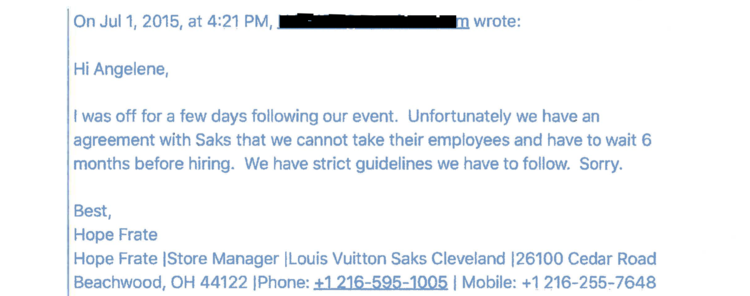

Hayes points to a June 2015 email exchange with Hope Frate, a store manager at a Louis Vuitton outpost in Cleveland, in which Frate informs her, “We have an agreement with Saks that we cannot take their employees and have to wait 6 months before hiring.” Frate continues, “We have strict guidelines we have to follow.” Hayes claims that this language mirrors what Saks’ Human Resources Director Marcia Miller told her “in or around December 2014.”

Ms. Miller allegedly “explained that Saks and the Leased Entities could relax the policy only by mutual agreement between the two companies that the Leased Entity was permitted to hire the given Luxury Retail Employee.”

Meanwhile, Ms. Wang claims in the complaint that she was prevented from seamlessly transitioning from her job as a Sales Associate at Saks to a role at a nearby Gucci or Prada store, as she was “warned [by a Gucci Store Manager] … that she would have to wait a ‘six-month cooling off period’ after leaving Saks in order to be hired by Gucci.” In a separate meeting in February 2016, she says that a Prada store “General Manager told [her] that Prada [also] has an agreement with Saks not to recruit Saks Luxury Retail Employees.”

In sum, Wang claims, “both representatives from Gucci and Prada were interested in hiring [her] while she was employed by Saks; however, they were restricted from doing so as a result of the no-hire agreement(s).”

Finally, New York-based Ms. Giordano states that she was told by “one headhunter of positions with Loro Piana, Louis Vuitton, and Brunello Cucinelli, for which she was well suited.” However, she claims that “the headhunter instructed [Giordano] that she could not place her in those positions … unless she quit her current job at Saks and waited to seek work again in the industry.”

By entering into such allegedly express arrangements, Saks and the Leased Entities are not only standing in the way of “a properly functioning and lawfully competitive labor market, in which each [of the] defendants would openly compete for the services of Luxury Retail Employees, including by hiring current employees from each other,” they are helping to fix the wages earned by employees “at artificially low levels,” the plaintiffs assert. This is because even just the threat of lateral hiring by competing companies is enough to “force employers to reactively increase compensation,” “enhance the terms of [individuals’] commission agreements,” and/or “match [any other] compensation terms” in order to “retain Luxury Retail Employees who are likely to join a competitor.”

These very “benefits of a competitive labor market” are diminished as a result of such arrangements between companies, which, the plaintiffs claim, “have been in place since at least 2014 and have been recognized, ratified, and enforced since that time.” They assert that the direct results of such provisions are not merely felt by Saks employees and those of its Leased Entities, but instead, they “negatively impact employee compensation throughout the luxury retail industry,” which is precisely why these “no-hire agreements are illegal and violate both antitrust and employment laws.”

“The intended and actual effect of these agreements is to suppress Luxury Retail Employees’ total compensation and to impose unlawful restrictions on Luxury Retail Employees’ mobility,” the plaintiffs continue on, further arguing that “because the defendants control a significant number and proportion of the luxury retail jobs in the United States, their no-hire agreements have reduced competition for Luxury Retail Employees, thereby suppressing Luxury Retail Employee pay.”

The agreements, themselves, and the larger “conspiracy” that is allegedly at play has “restricted trade and [is] per se unlawful under federal law,” as such behavior places “illegal horizontal restraints on competition,” the plaintiffs claim. “Indeed, the no-hire agreements had substantial anticompetitive effects, including, but not limited to, eliminating competition, preventing the plaintiffs and members of the proposed class from obtaining employment and earning compensation in a competitive market, reducing compensation, and preventing or limiting employment opportunities and choice with respect to such opportunities.”

The three plaintiffs claim that Saks and each of the Leased Entities “have acted in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act,” and as a result, they are seeking certification of their class action to enable other similarly situated individuals – potentially “all persons in the United States employed by at least one of Defendants at any time from September 30, 2015 until the effects of the defendants’ conduct ceases” – to join in the lawsuit and any ultimate settlement (assuming there is one), while also seeking a jury trial, and monetary damages, among other remedies.

TFL reached out to the defendants for comment, and a rep for Gucci’s parent company revealed that they do not have a comment.

*The case is Giordano et al v. Saks Incorporated et al, 1:20-cv-00833 (EDNY).