Two high-profile beauty brands have settled a trademark fight over the use of the word “DIVINE” on their respective products. On the heels of model Rosie Huntington-Whitely’s clean cosmetics brand Clean Beauty Collaborative, Inc. d/b/a Rose Inc. filing a lawsuit against Pat McGrath Cosmetics (“PMC”), the eponymous company of one of fashion’s most celebrated makeup artists (and subsequently filing an amended complaint), alleging that PMC threatened to file suit against Rose Inc. unless it cease its use of the word “DIVINE” on its products, the clash has come to a close, with Rose Inc. lodging a notice of voluntary dismissal with a federal court in Northern California on September 1.

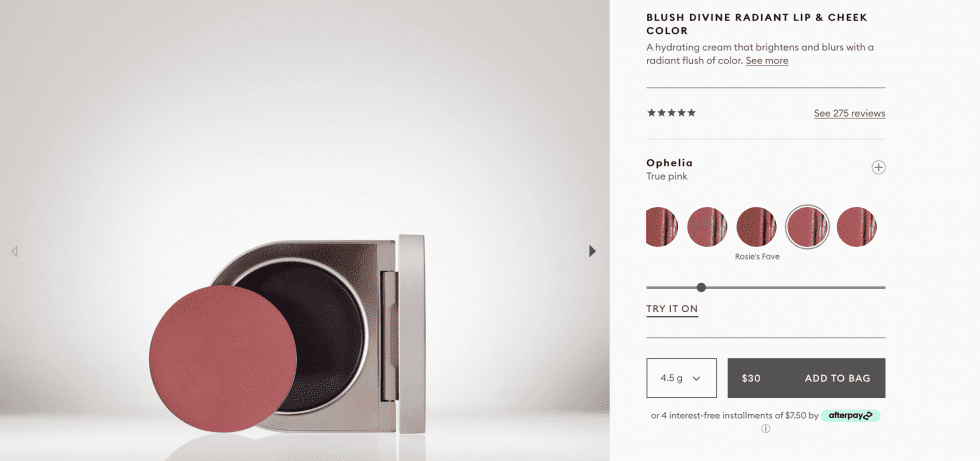

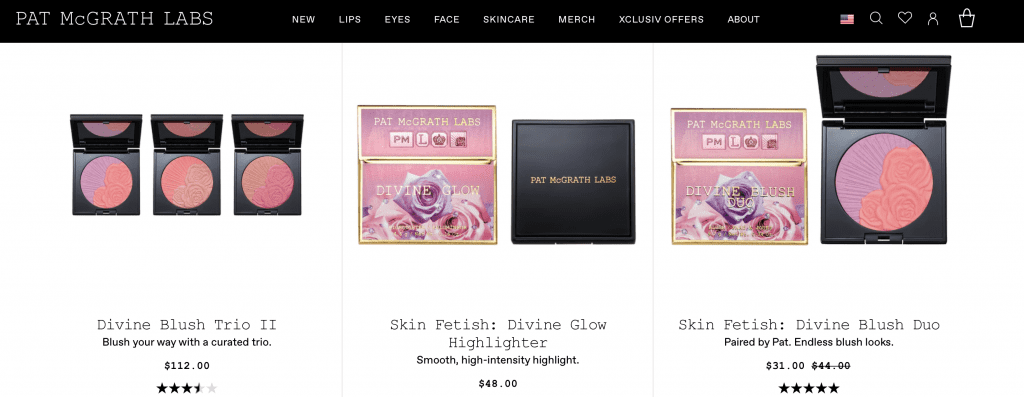

Rose Inc. first filed its lawsuit against PMC in January 2022, alleging that it received a cease-and-desist letter from counsel for New York-based PMC, which accused Rose Inc. of infringing “the Pat McGrath family of ‘Divine’ marks” by way of its “Blush Divine Radiant Cheek & Lip Color.” (A trademark “family” consists of “a group of marks having a recognizable common characteristic, wherein the marks are composed and used in such a way that the public associates not only the individual marks, but the common characteristic of the family, with the trademark owner.” PMC, for example, uses the “Divine” mark across an array of products – from its “Divine Blush” and “Divine Glow Highlighter” to its “Divine Skin Prep and Prime Duo” and “Divine Brush Duo.”)

In its letter, PMC asserted that its “Divine” marks “have become associated exclusively with Pat McGrath in the cosmetics industry,” and demanded that Rose Inc. “immediately and permanently stop making, importing, selling, and offering to sell any cosmetic under a DIVINE -formative mark,” and that it also deliver to PMC “for destruction all existing inventory of the current Blush Divine product and all promotional materials depicting them.”

Despite counsel for both sides engaging in discussions in January, Rose Inc. asserted that they were unable to work out their differences, thereby, prompting it to file a declaratory judgment and unfair competition complaint, in furtherance of which it sought a declaration from the court that “the name ‘Blush Divine Radiant Cheek & Lip Color’ and the associated cosmetic product [on] which it is used, do not infringe upon any of the trademarks or other intellectual property rights of PMC,” as it is engaging in fair use of the term. Beyond that, Rose Inc. was angling for a declaration from the court that PMC does not own protectable rights in the “Divine” marks because “the term ‘divine’ is generic, so highly descriptive as to be incapable of functioning as a trademark through acquired distinctiveness, or is merely descriptive and lacks secondary meaning such that the relevant purchasing public does not recognize DIVINE as being a common characteristic to indicate that PMC is the common origin of the goods or services in either the beauty or cosmetic industry.”

Rose Inc. also lodged unfair competition claims, arguing that by “promoting” and “advertising” that it “has ownership to a protectable DIVINE-formative family of marks” when it does not, PMC “made a false or misleading representation of fact about [its] ownership rights” and that such “unlawful, unfair or fraudulent acts and practices” caused Rose Inc. to be damaged.

While the terms of the parties’ settlement are confidential, it is worth noting that Rose Inc.’s Divine products – namely, its Color Divine Blush Contour and Blush Kit and its Divine Color Blush Brush Set – have been renamed in its website so that they no longer make use of the “Divine” name.

Not the only case that has raised the idea of trademark families as of late, Levi’s made a similar claim in a more recent suit. The denim giant filed a trademark lawsuit against the owner of a recycled denim brand this summer, claiming that by using the “Green Tab” name for his brand, he is running afoul of its rights in the mark, which is part of a family of “famous” marks, including its red tab. In its complaint, Levi’s claims that its use of various colored fabric tabs and the related word marks amount to “a group of marks having a recognizable common characteristic, wherein the marks are composed and used in such a way that the public associates not only the individual marks, but the common characteristic of the family, with the trademark owner.” That case is still underway before the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California.

It is worth noting, of course, that there is no telling that the court would have been found that PMC’s various uses of “Divine” amount to trademark uses for the very reason cited by Rose Inc. – it is potentially generic or descriptive, and thus, is incapable of functioning as an indicator of source – or that Rose Inc.’s use is for the purpose of source-indication and thus, infringing (assuming that PMC could show likelihood of confusion). A win for PMC on this front could have been made more difficult by the nature of the goods at issue – cosmetics, which are regularly marketed by way of style names that make use of “words that are not literal color descriptions,” as Anastasia Beverly Hills argued in response to the lawsuit waged against it by Hard Candy over its product style names back in 2019.

At the same time and for some of the same reasons, it is not difficult to imagine the court pushing back against PMC’s family argument, which would require a showing that PMS is not “simply using a series of similar marks,” but that there is a sufficient level of “recognition among the purchasing public that the common characteristic is indicative of a common origin of the goods,” as the Federal Circuit stated in its decision in J & J Snack Foods Corp. v. McDonald’s Corp.

The case is Amyris, Inc., et al. v. Pat McGrath Cosmetics, Inc., 3:22-cv-00567 (N.D. Cal.)