It is widely known that brands around the world have a long history of destroying over-ordered, under-sold offerings – from logo-adorned leather goods to non-expired cosmetic products (often referred to as deadstock) – rather than selling off these excess goods at a discount within their own stores or more discreetly by way of off-price chains or still yet, by donating the items to charitable organizations. Fashion brands – and in particular, apparel companies whose models depend on the high-turnover of cheap, disposable wares – are no strangers to being criticized for playing their part in the increasing volumes of wasted products entering landfills globally each year. However, in recent years, developments at a legal and advisory level in Europe – which have focused on improving sustainability practices by brands and retailers – seek to prevent these environmentally unfriendly activities.

In January 2020, for instance, a wide-ranging anti-waste law was passed in France, which will ban the disposal (i.e. landfilling/incineration) of any unsold non-food products once it is implemented. According to the French government, some €630 million ($757.79 million) worth of unsold non-food products are destroyed every year in France, including between 10,000 to 20,000 tons of textile products. The closely-watched new law, which is set to come into effect at the end of 2021/start of 2022, will subject companies to more than 100 new sustainability-centric provisions, such as those that require the systematic phasing out of automatic paper receipts and single use plastic in fast food restaurants, for instance; followed by the outright ban on all single-use plastics by 2040.

Of particular interest for the fashion industry is, of course, the prohibition on the destruction of an array of different types of unsold goods, including fashion items, and the push to secure greater retailer accountability in relation to stockpiled inventory. In accordance with the law, companies will have to donate or recycle their unsold items, including clothing, shoes, cosmetics, daily hygiene products, electronics, books, household appliances, etc., as long as those products do not “pose a health or safety risk.”

For unsold basic necessities, companies will be required to allow their use, for example by donating them to specifically accredited associations that can ensure such products are utilized by an end customer in accordance with their purpose. Failure to comply with the new law may expose companies to financial penalties of €15,000 per infraction. And in addition to any potential monetary damages, the regulatory body in charge of the protection of competition and consumers may be entitled to publish any infractions online or in the press at the expense of the company being fined, which could expose the offender to substantial reputational damage, particularly as sustainability initiatives continue to prove important to consumers across the globe.

In alignment with the French law, the European Commission announced an investment of €101.2 million in projects under the LIFE program for Environment and Climate Action, an initiative that aims to see EU member states cut their waste production in half by 2030. In February 2020, the executive vice president of the European Commission, Frans Timmermans, confirmed that the project is intended to transform retailer behavior and enhance sustainability.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the Environmental Audit Committee (“EAC”) called on the government to press brands to take greater responsibility for the waste that they create on the basis that while some parts of the fashion industry are reducing their carbon and water consumption, these improvements are outweighed by vast volumes of product waste. One of the Committee proposals pushed for retailers to pay a fine for each item of deadstock they produce, so that it can pass through a more sustainable end-of-life process. The UK government did not act on any of the EAC’s recommendations, but it did, however, acknowledge the issues, pointing to proposed actions being taken as part of its 25 Year Environment Plan and Resources and Waste Strategy.

Balancing Sustainability and Brand Enforcement

Consumers are currently more mindful than ever before of what is happening to unused goods, and therefore, these anti-waste initiatives are generally well received at this level. Brands have been a bit more hard pressed to make a clean break from their old ways. While brands in the retail and consumer products industries recognize the value of demonstrating transparency and sustainability in their supply chains, many have conflicting – yet legitimate – concerns surrounding the protection of their brand image on the basis that preserving product scarcity and prestige is critical to the success and viability of, in particular, prestige or luxury brands. (This neatly parlays into the unwillingness of many brands to allow trademark or copyright-bearing deadstock textiles to enter into the market without their authorization, which raises infringement issues – as well as questions about supplier contract provisions – in connection with the use of source-identifying materials, such as Burberry’s trademark-protected check print and Fendi’s Zucca pattern, by brands like AVAVAV).

With such budding legislation in France in mind and given similar pushes in other jurisdictions, retailers, producers, distributors and online trading platforms are being forced to determine how best to donate, reuse, repurpose, recycle and/or upcycle unsold items in a way that minimizes the risk of brand degradation that may be suffered as a result of luxury products circulating outside of brands’ carefully controlled authorized distribution chains. This need for a clear strategy on excess or obsolete inventory has been made even more pressing as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, since at the height of the pandemic, lockdown measures and a larger shift in consumers’ shopping habits put a significant dent in sales across nearly an entire season by retailers, thereby, creating enormous amounts of unsold inventory in many cases that brands needed to off-load.

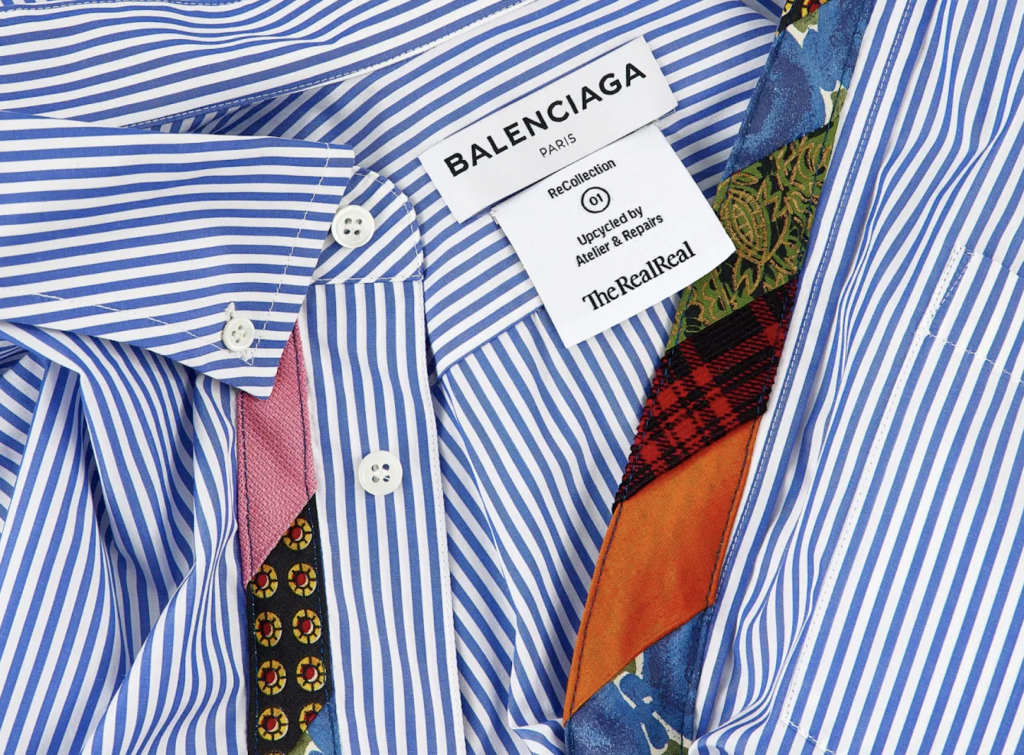

In light of enduring overproduction issues and budding legislative attempts to stomp out waste, the fashion industry is already seeing the incorporation of start-up companies that seek to assist companies with reducing their waste, in particular, by offering to act as intermediaries between affected companies and third parties – whether those be non-profit organizations, off-price retailers or resale sites – to facilitate the transfer of unsold goods. Luxury resale site The RealReal, for instance, recently unveiled a new venture with Balenciaga, Dries Van Noten, Stella McCartney, Jacquemus, Simone Rocha, Zero + Maria Cornejo, Ulla Johnson, and A-Cold-Wall in furtherance of which it is selling a small run of garments refashioned from the aforementioned brands’ excess textiles.

Reflecting on The RealReal’s new ReCollection, which launched early this month, and the larger push for more sustainable ways of dealing with deadstock, designer Stella McCartney stated, “We’ve seen many designers come out of this moment of pause and begin to upcycle old fabrics, to repurpose and redesign and give things a second life,” noting that “this is one way the industry can tackle its enormous waste problem.”

With consumer pressure rising in response to media reports about discarded inventory and a growing amount of published waste data, companies are likely to find ways to bank on the push towards circularity just as more countries are expected to join France in advancing measures aimed at requiring the sustainable management of waste. In short: this is an area for brands and retailers, alike, to keep a close eye on.

Nicola Jayne Conway is a commercial lawyer in Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner’s Technology and Commercial Team, and Retail and Consumer Products Group.