Deep Dives

> By way of a nostalgia edit, companies can create contemporary fashion products with a brand’s cultural and symbolic heritage to meet the cultural zeitgeist.

> Using designs from an archive might help companies to revive and/or maintain rights in these already-established assets.

> In jurisdictions that require use of a trademark, like in the United States, an archive can provide evidence of past uses of that mark.

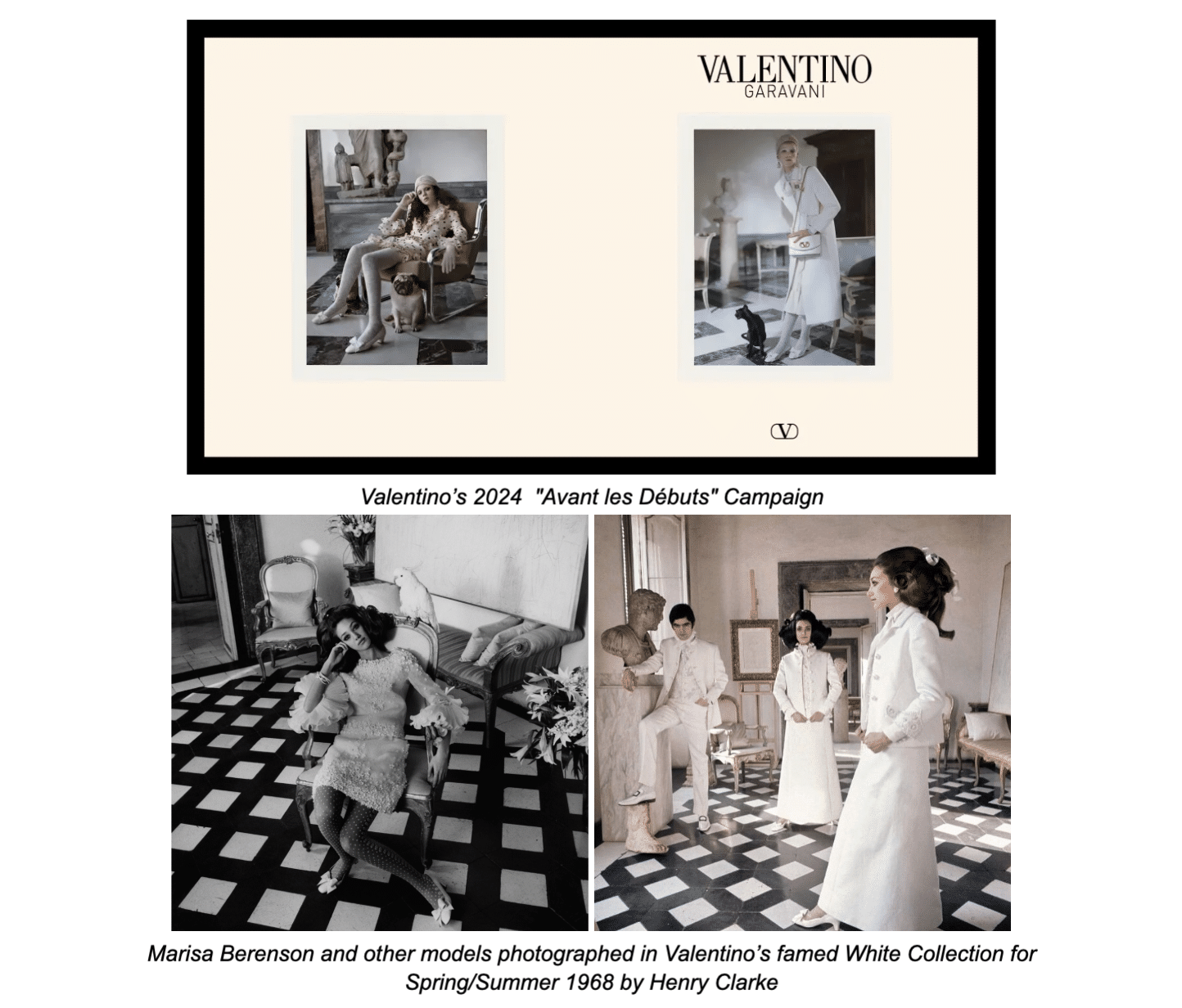

When Alessandro Michele became creative director at Valentino in March 2024, he released a statement praising the brand and its “collective history,” a history that included a rich “cultural and symbolic heritage.” What did he mean by that, and why would he emphasize the past when taking the reins of a fashion brand that has contemporary relevance? When he presented his first collection and unveiled his first advertising campaign for Valentino, his meaning was evident. Images of the “Avant les Débuts” campaign clearly referenced Valentino advertisements from the 1960s featuring Marisa Berenson in the famous White Collection. The collective history of the brand was mined for present visual messaging and designs.

Michele’s visual citations to past Valentino campaigns and designs were not out of character. We have all seen what we might call nostalgia edits in fashion and pop culture. Did you know that Paris and Nicole are back for a Simple Life encore? As of New Year’s Day, you can even pick up a “re-edition” of the “iconic collaboration” between Louis Vuitton and Takashi Murakami.

Never immune to a nostalgia edit, mining the symbolism inherited from a brand’s past was central to Michele’s designs at Gucci. His debut for the Kering-owned brand in 2015 was recognized as much for his signature bohemian, eccentric, and androgynous style as it was for his subtle tweaking of Gucci’s own heritage. Who can forget Michele’s take on the classic Gucci loafer (a signature design of the brand since 1953, according to brand lore), which added fur and transformed the shoe into a slide? Vogue deemed it the “It Shoe of Fall 2015.”

Another celebrated design of Michele’s during his Gucci tenure: The Dionysus bag. This, too, was a riff on a past design. A bright red version from the 1970s was on display in the Gucci Museum in Florence, Italy, until the museum closed in 2017. Michele’s 2015 version of the Dionysus swapped the bright red body for Gucci’s GG pattern, while keeping the snake decoration. And, of course, there was Michele’s modern take on the historic Gucci Flora pattern, created in 1966 by the Italian illustrator Vittorio Accornero for Princess Grace at the request of Rodolfo Gucci. Through Michele’s vision, snakes, bees, and other bugs were given as much attention as the flowers, and the creation of a Gucci Garden Collection was born.

And why creatively revisit one design and motif from a brand’s cultural and symbolic heritage when you can mishmash them all together in one accessory or even an entire collection? Put the Dionysus bag in a revisited Flora pattern, and add Flora to Gucci sneakers with a “new” Blue-Red-Blue stripe? Profiles of Michele during his tenure at Gucci highlighted his knowledge of the brand’s past as they also implicitly promoted the new products he created.

Of course, if you are Alessandro Michele, archival inspiration and nostalgia rooted in a brand’s cultural and symbolic heritage are not just a reference to the past. Mixing visual cues and design nods to Tom Ford’s 1990s velvet suits for Gucci with the Gucci horsebit and other equestrian codes (a whip! a harness!) to create a consumer frenzy on a brand’s 100th birthday is all in a day’s work. And again, why stop at one brand’s cultural and symbolic heritage, when you can create contemporary, hot fashion with two? (More on the intellectual property implications of co-branding here.)

A nostalgia edit that creates contemporary fashion products with a brand’s cultural and symbolic heritage to meet the cultural zeitgeist certainly is not confined to Michele’s work at Gucci or now, at Valentino. Just look at Maximilian Davis’ revisiting of Salvatore Ferragamo’s 1950s gold sandals, and the role that ballet (and the ballerina flat that Salvatore Ferragamo designed for Audrey Hepburn) had in the Spring/Summer 2025 Ferragamo collection.

In an industry where novelty often seems more important than the past, and creative directors are in search of present trends to market to consumers, why mine a brand’s archive – a collection of past designs and corporate ephemera, including advertisements – for a collection? Apart from their visual appeal, are fashion collections that reference a brand’s cultural and symbolic heritage good fashion business? Is a nostalgia edit good fashion management? And perhaps most importantly, what say do intellectual property rights have in nostalgia edits, archival fashion drops, and collaborations that mash two brands’ symbolic and cultural heritage together?

It turns out that intellectual property law may have a lot to say about nostalgia edits and the creation of fashion inspired by an archive. Remixing archival designs and a brand’s cultural and symbolic heritage can help a brand acquire present (and future) IP rights to leverage in the market. At the same time, while using designs from an archive might help companies to revive and/or maintain rights in these already-established assets, it also may require extensive rights clearances and what cultural heritage professionals know as provenance research.

Consider copyright law’s role in a fashion archive. As Rosie Burbridge notes in her European Fashion Law book, raiding the fashion archive for creative inspiration might mean being inspired by a photograph from a long-lost advertising campaign whose copyright is uncertain. Is there a record of the photographer and is the brand’s contract with them on file? If ownership of a copyright is uncertain, some jurisdictions like the United Kingdom and the European Union might offer opportunities to use so-called orphan works.

At the same time, without legislation specific to orphan works, in house legal offices in the U.S. representing brands that want to use past promotional images (or even comment on their cultural significance, like VOGUE did when it invited Brooke Shields to tell the backstory of that iconic Calvin Klein ad) might find themselves troubleshooting claims of copyright infringement as they try to gather whatever permissions they can. The topic of permissions was on the mind of Jessica Barber, Calvin Klein’s former Historian and Senior Archivist, when I spoke with her about what makes an iconic product in the fashion industry.

To avoid accusations of copyright infringement, a fashion brand could always re-create an iconic image that defines their brand’s symbolic and cultural heritage, much as Alessandro Michele liberally re-created the archival images with Marisa Berenson. This re-creation, however, requires parsing copyrightable expressions from uncopyrightable ideas. While a brand might get away with copying itself, copying the expression of a photographer who has not assigned his copyright to a brand or otherwise created a work for hire might have more serious implications.

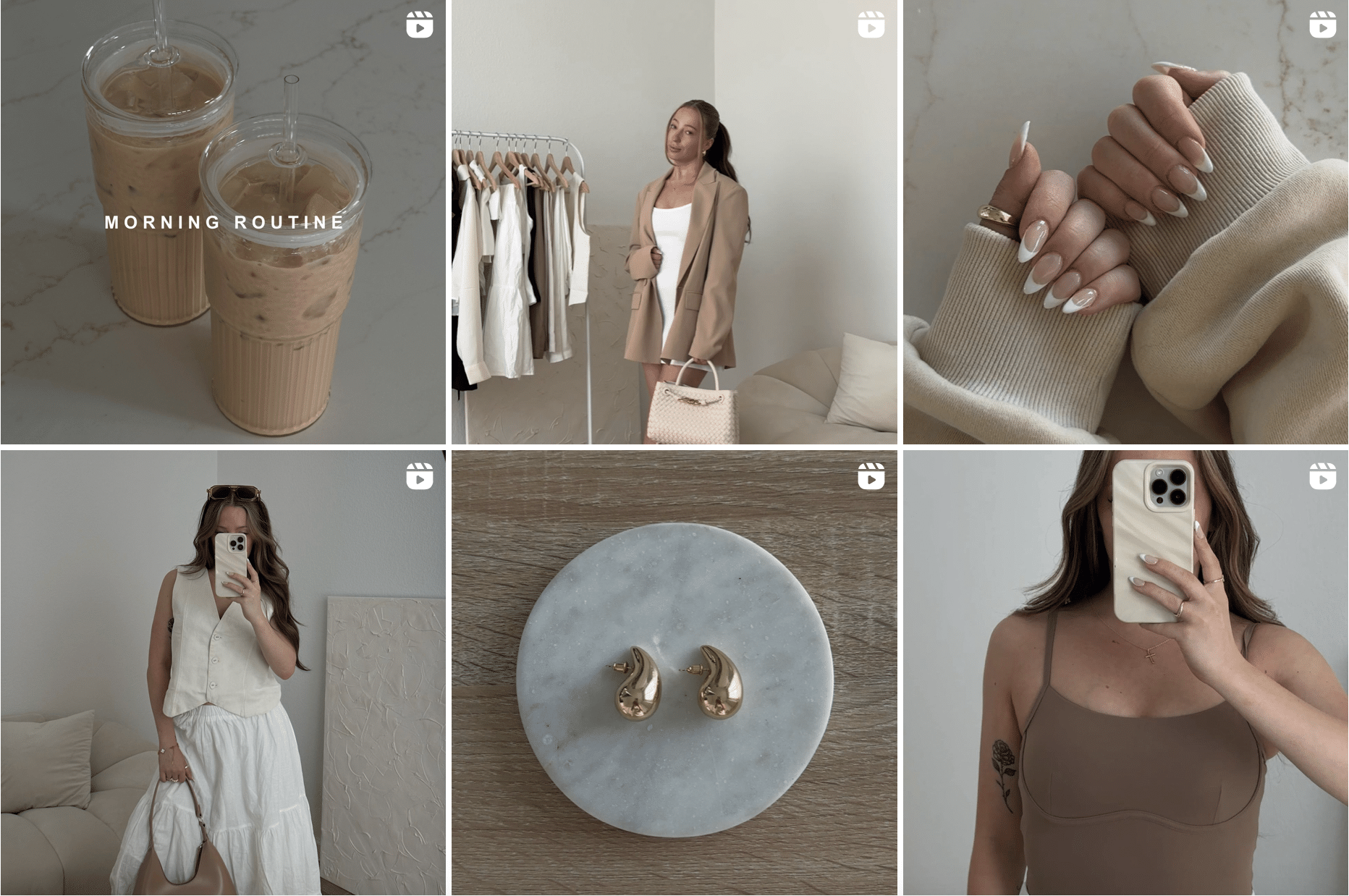

Parsing expressions from ideas is not always that easy or for that matter, an exculpation of potential liability. Look no further than a case in which two influencers are currently arguing over whether a minimalist composition is a copyrightable expression – is a fashion vibe expression or idea? Forget separability, this might be the copyright fashion issue of our time.

Then there is trademark law. Unlike copyright law, trademark law is supposed to be about meanings, symbolism, and messages to consumers. Using designs from the past can mean that a brand has a stronger trademark right in that design because consumers have, over time, come to associate the design with the brand. In other words, secondary meaning might be stronger for archival designs than for new ones, even if that new design is combined with a marketing bonanza. On the other hand, designs that have lain dormant in the archive may have been forgotten by consumers. A nostalgia edit is well and good if consumers remember the design. If consumers do not remember the design and do not associate it with the brand, it is worth examining whether trying to reclaim trademark rights in a design effectively abandoned through nonuse is worth the creative and legal effort.

In jurisdictions that require use of a mark, like in the United States, an archive can provide evidence of past uses of a mark. First to file jurisdictions may also extend some benefits to pre-use. Gucci, for example, relied on testimony from its archivist when it sued Guess for trademark infringement in Italy to show a continuous prior use of marks which it had later registered. Evidence of prior use found in a brand’s archive might provide avenues to attack a competitor’s use of similar marks or even grounds to invalidate a competitor’s trademark registration, depending on the jurisdiction.

Michele’s reference to a brand’s symbolic and cultural heritage also raises the possibility that a brand’s archive, and the evidence within it, might be of interest to members of the public, whether they are consumers of the brand’s product or not. A nostalgia edit brings up memories for everyone: even if you could not afford a Murakami x Louis Vuitton bag in the 2000s, your mind is likely indelibly impressed with the pop culture reference of Paris Hilton carrying one, even as part of a parody skit on SNL. That is why wearing archival fashion can also inspire outrage and shock, like Kim Kardashian’s Marilyn Monroe moment on the 2022 Met Gala red carpet. We care about the cultural meanings in a piece of archival fashion, the connections to celebrities and historic moments even more than the connections to a brand, alone.

Because brand archives, and even for-profit museum collections, may not be subject to the professional obligations and best practices that non-profit museums and other cultural institutions implement when managing tangible fashion assets, a brand’s lending of a piece of fashion from their archive can operate in a grey zone between private property rights and the protection of cultural property. Sarah Scaturro, the Eric and Jane Nord Chief Conservator at the Cleveland Museum of Art, raised public awareness about why wearing archival fashion is problematic from a conservator’s standpoint in the days and weeks surrounding Kim Kardashian’s red carpet appearance. (I delve more deeply into the ethics and legal ramifications of wearing archival fashion with Sarah on A Fashion Law Dinner Party, and you can listen to our conversation here.)

While archival fashion might at first point to tangible property rights more than intangible intellectual property rights, a public interest in a brand’s past fashion products can also shape intellectual property rights in contemporary fashion collections inspired by an archive and re-editions of a brand’s past designs. Consider that museums, from the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art to public museums abroad like Florence’s Museum of Costume and Fashion, are collecting archival fashion or accepting donations from brands themselves.

As museums photograph the fashion in their collections they might create new copyrights in photographs that require additional permissions from non-brand institutions. Reproducing this image of a 2016 edition of Versace’s safety-pin dress requires permission from Art Resource and the credit “© The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.” Other jurisdictions, like Italy, might have image rights under cultural property law that act like mutant copyrights, extending permissions to reproduce a photograph of archival fashion long after any other copyright, or even design patent or design right, has expired.

Image rights over works of art in public museums are already affecting Creative Directors’ inspiration – just think of how Jean Paul Gaultier’s Le Musée collection was confined by the Uffizi’s image rights in Botticelli’s Birth of Venus composition.

When a brand’s fashion is inspired by their archive, or even by a museum’s collection that is made up of a brand’s archival fashion or connected to iconic works of art, the intellectual property a brand might claim in the contemporary fashion it creates might be limited or expansive. Like the curiosity cabinets of the Renaissance, a fashion archive can provide numerous legal avenues for a brand’s intellectual property.

Felicia Caponigri is a Visiting Scholar at Chicago-Kent College of Law and the Founder of Fashion by Felicia, LLC. An attorney by training and an academic by calling, she hosts A Fashion Law Dinner Party, a podcast which explores the links between design, heritage, and the law with guests from the fashion industry.