Ahead of the start of the Olympics today, the robust rights held by the International Olympic Committee and in the U.S., the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee (“USOPC”) are garnering attention, in part because of the well-known willingness of these entities to take legal action when their trademarks are used without authorization. “The Olympics benefits from extra special trademark protection here in the United States. Unlike in other countries, the federal government does not fund Team USA, so our athletes mostly rely on sponsorship dollars to compete,” Dorsey & Whitney’s Fara Sunderji wrote recently, noting that “when advertisers use the Olympics brand without authorization, the USOPC views this as a loss of sponsorship dollars” – and very well may take legal action.

The basis for such actions is, of course, trademark infringement – but that is not the only cause of action that the USOPC relies upon. In fact, the organizing body routinely alleges violations of the Ted Stevens Olympic and Amateur Sports Act. The almost 50-year-old federal statute enables the USOPC to take civil action against entities for the remedies provided in the Lanham Act if they use “for the purpose of trade, to induce the sale of any goods or services, or to promote any theatrical exhibition, athletic performance, or competition, any trademark, trade name, sign, symbol, or insignia that falsely represents an association with, or authorization by, the USOPC or the IOC” without authorization.

As for what those trademarks are, the International Olympic Committee and USOPC maintain the exclusive rights to use (and prevent others from using) various words and logos in connection with clothing and accessories, sporting events, posters, hotels/temporary accommodations, etc. including (but not limited to) the “United States Olympic Committee,” “Olympic,” “Olympiad,” “Cities Altius Forties,” and “Paralympic” word marks, and the interlocking blue, yellow, black, green, and red rings logo.

As distinct from traditional trademark infringement claims, which require a showing of likelihood of confusion, the USOPC need not make such a showing unless the allegedly infringing mark is not identical to a USOPC-owned mark. “Unlike other trademark owners, to make a claim against a third party’s use of a mark, the USOPC does not need to assert that the use of the mark is likely to create consumer confusion, dilute the distinctiveness of the USOPC’s marks or tarnish the USOPC’s marks,” Wilkinson Barker Knauer stated in a recent note.

Hardly a hypothetical threat, the USOPC has been known to actively enforce its trademark rights – most recently filing a new lawsuit against YouTube star Logan Paul’s energy drink company Prime. In the complaint that it lodged with the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado on July 19, the USOPC alleges that Prime is running afoul of the Ted Stevens Act and the Lanham Act by way of its unauthorized use of various Olympics marks. In connection with the manufacturing, marketing, and sale of one of its drinks, which features Olympic gold medalist and NBA star Kevin Durant, the USOCP claims that Prime uses the OLYMPIC word mark, “including two uses of ‘Kevin Durant Olympic Prime Drink,’ ‘Celebrate Greatness with the Kevin Durant Olympic Prime Drink,’ ‘Olympic Achievements,’ ‘Kevin Durant Olympic Legacy,’ and other uses.”

“Prime Hydration has used … Olympic-related terminology and trademarks on product packaging, Internet advertising and in promotions featuring a Prime Hydration flavor and athlete Kevin Durant,” the USOCP alleges in its complaint, arguing that such use is “willful, deliberate, and in bad faith.”

The Olympics body sets out claims of violations of the Ted Steven Act, trademark infringement and dilution, unfair competition, and violations of the Colorado Consumer Protection Act. In furtherance of the latter, the USOCP asserts that Prime has made “misleading use of the infringing marks [that] causes a likelihood of confusion or of misunderstanding as to the source of the products or services being promoted by Defendant.”

It is seeking injunctive relief and monetary damages, including “damages for harm to its sponsorship agreements” and an award of “the lost sponsorship costs” associated with placing USOPC marks on products and in advertising.

The bigger picture here is that companies, including those in the fashion and luxury realm, are increasingly looking to target sports fans and bank on the sizable viewership boasted by the Olympics – which is expected to attract 9.7 million spectators – and other notable sporting events. One need not look further than LVMH, which is sponsoring the games. This will see “LVMH’s cosmetics brand Sephora sponsoring the Olympic torch relay. Berluti designing France’s opening ceremony uniforms. Jeweler Chaumet crafting the Olympic medals, [which] will rest in cases designed by Louis Vuitton,” the AP reports.

The extent of the French luxury goods conglomerate’s involvement is “unprecedented for a luxury brand,” Bernstein luxury goods analyst Luca Solca said this week. Meanwhile, retail analyst Matt Powell noted that the involvement of brands like those under the LVMH umbrella in the sporting segment “shows how important sports is to retail in the world today. It gets a tremendous amount of media attention and personal attention on the part of the consumer. So, there’s a recognition that there’s an opportunity to harness that interest and introduce those folks to their brands.”

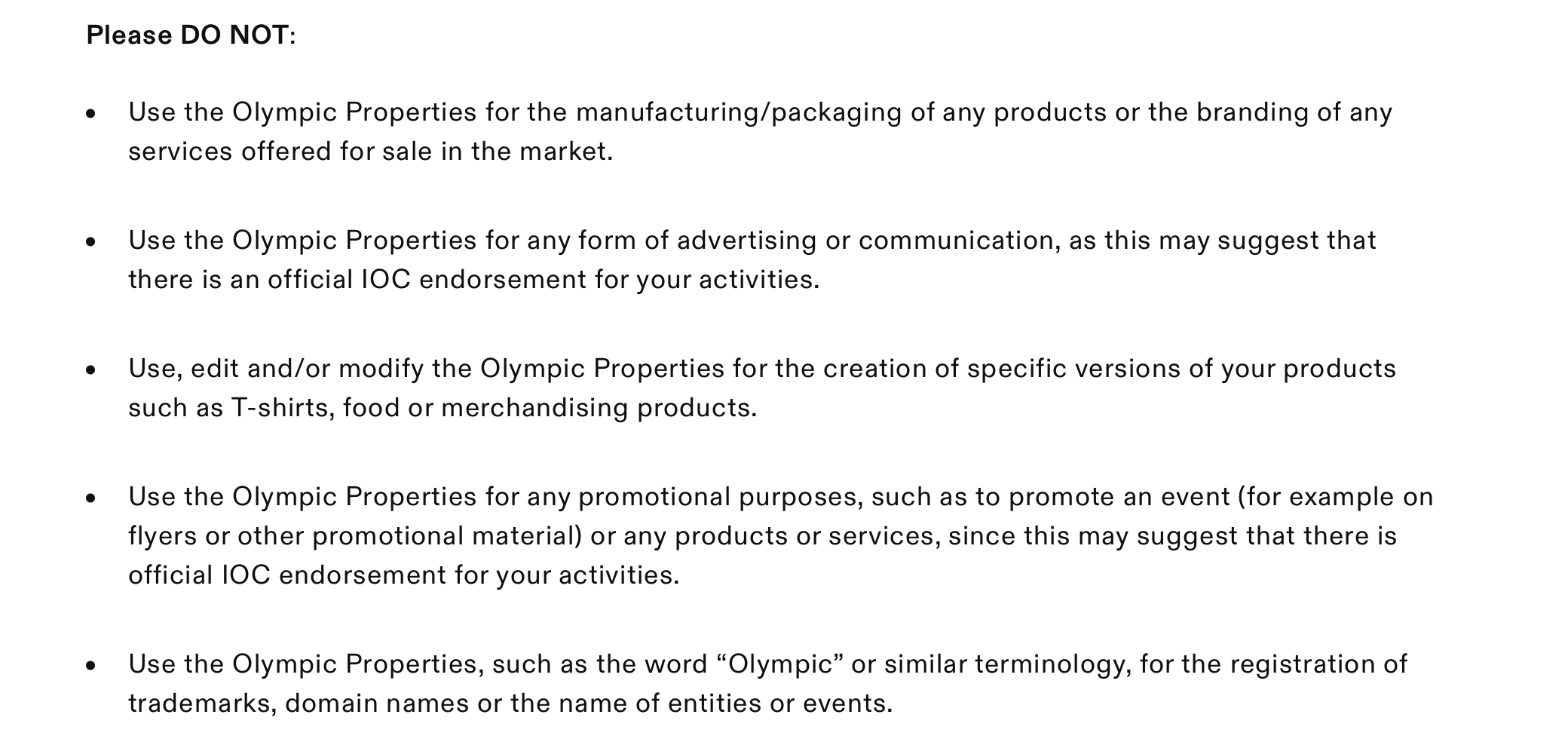

LVMH’s reported 150 million-euro ($162 million) financial contribution to play sponsor for the Paris 2024 games undoubtedly comes with rights to use various Olympics trademarks. However, the litigiousness of the USOPC leaves other brands that are looking to bank on the games for marketing purposes (by using the Olympics marks in a trademark capacity) in something of a tricky spot. While overt commercial uses of the Olympics marks are likely out of the question for companies that have not entered into formal licensing agreements with the organizer, they are not entirely out of luck.

“Marketers have to be creative without relying on USOPC-owned intellectual property or athlete reputations,” Sunderji stated, suggesting that “subtle nods to breakout athletes, shocking wins, or heated competitions using generic – but creative – methods” may be the best way forward.