Deep Dives

Chanel and What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”) are currently clashing over equitable remedies in phase two of trial in a trademark case that centers on the resale market. On the heels of a multi-week jury trial early this year and a jury verdict that unanimously found that WGACA had engaged in willful trademark infringement, false association, unfair competition, and false advertising, Chanel is angling for a permanent injunction, as well as additional monetary damages, including the WGACA’s profits.

Part of what the luxury goods titan is seeking on the injunction front is for WGACA to “prominently display a disclaimer on its website and on physical products.” In particular, Chanel wants WGACA to make it clear(er) to consumers that Chanel has not guaranteed the authenticity of the Chanel products that WGACA is selling and that WGACA’s operations are neither affiliated with nor authorized by Chanel.

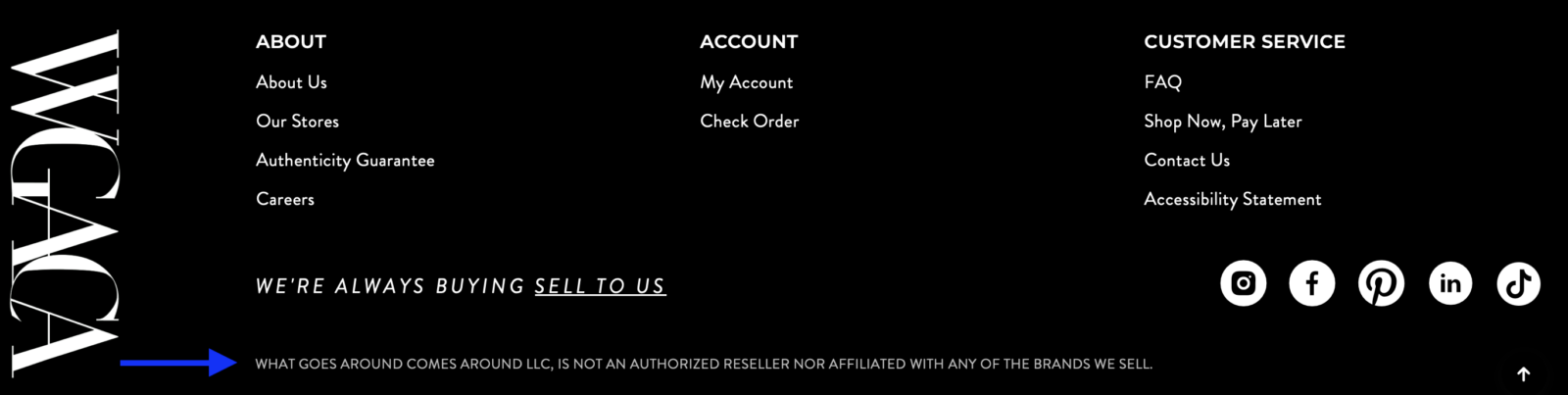

Counsel for Chanel has argued that the existing disclaimer that WGACA displays on its website – in which it states that it “is not an authorized reseller nor affiliated with any of the brands we sell” – is not strong enough. As such, Chanel is angling to get the court to require WGACA to “prominently place and clearly and conspicuously feature [a] disclaimer on any webpage or social media post where CHANEL-branded items products are being offered for sale.” Chanel’s proposed disclaimer: “WHAT GOES AROUND COMES AROUND HAS NOT BEEN AUTHORIZED BY CHANEL TO SELL THIS ITEM. THIS ITEM HAS NOT BEEN AUTHENTICATED BY CHANEL.”

Chanel’s push for the use of the aforementioned disclaimer to alert consumers about its lack of affiliation with – or endorsement of – WGACA and its offerings is far from a novel issue, as disclaimers are routinely been used in an array of contexts in an effort to diminish the risk of consumer confusion and potentially enable third parties to avoid landing on the receiving end of trademark infringement allegations. And in fact, a number of cases – both new and more well-established – have put disclaimers in the spotlight and are worthy of attention, as parties and courts, alike, shed light on the state of disclaimers and how they can/should be utilized.

In a string of cases over the repackaging and/or upcycling of goods ranging from spark plugs to luxury watches, courts have held that disclaimers may allow for the unauthorized use of another party’s trademark without creating consumer confusion. The Supreme Court, for instance, held in Prestonettes v. Coty in 1925 that the unauthorized use of another’s mark to indicate that the trademarked product was a component in a new product was not likely to cause confusion by virtue of the use of a disclaimer. (In that case, the disclaimer stated, “Prestonettes, Inc., not connected with Coty, states that the contents are Coty’s [giving the name of the article] independently rebottled in New York.”)

Fast forward to 1947 and in Champion Spark Plug v. Sanders, the Supreme Court held that adequate disclosure by a product’s restorer, such as through disclosures that label the second-hand good as “used” or “repaired,” can constitute full disclosure of the product’s origins, thereby, making consumer confusion unlikely.

Since then, various courts have relied on the Supreme Court’s decision in Champion when considering whether the unauthorized use of another’s trademark amounts to infringement. In Hamilton Watch v. Vortic, for instance, a case that pitted Swatch subsidiary Hamilton International against custom watch-maker Vortic over upcycled watches containing Hamilton parts and trademarks, the Second Circuit concluded in 2021 that Vortic sufficiently disclosed that its timepieces contain refurbished parts not affiliated with Hamilton. As a result, Vortic was able to avoid trademark infringement liability.

And more recently, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed the lower court’s decision in the Rolex Watch USA, Inc. v. BeckerTime case. While the court ultimately found earlier this year that BeckerTime infringed Rolex’s trademarks by selling preowned Rolex watches with various modifications, it considered the role of disclosures, suggesting that the proper use of disclosures could have impacted the element of consumer confusion.

While disclaimers have been commonly – and in certain cases, effectively – used as a way to reduce the potential for consumer confusion caused by the unauthorized use of another’s trademark, the use of disclaimers does not necessarily pave the way for a party to sidestep infringement liability. One need not look further than the trademark infringement and dilution case that Hermès successfully waged against Mason Rothschild (real name Sonny Estival) over his advertising and sale of artwork-linked non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) called MetaBirkins as an example.

Disclaimers have been an issue from the outset in that case, with Hermès arguing in its January 2022 complaint that following the receipt of a trademark-centric cease-and-desists letter from Hermès, Rothschild updated the Metabirkins website “to add a disclaimer that excessively uses the HERMÈS mark three times.” According to Hermès, the disclaimer – which states, “We are not affiliated, associated, authorized, endorsed by, or in any way officially connected with the HERMES, or any of its subsidiaries or its affiliates. The official HERMES website can be found at https://www.hermes.com/” – “unnecessarily links to Hermès’ website and capitalizes the HERMÈS mark.”

Beyond that, Rothschild’s “uses of the HERMÈS mark in conjunction with his use of the BIRKIN mark, and the display of the METABIRKINS bags, serves only to create a confusing impression among consumers as to Hermès’ sponsorship of the METABIRKIN NFTs and the METABIRKINS website,” Hermès’ counsel argued.

Still yet, Hermès took issue with the fact that the METABIRKINS website was “the only advertising channel” on which Rothschild included a disclaimer. “The disclaimer is notably absent from Rarible, the current point of sale for the METABIRKINS NFTs,” per Hermès, which noted that the disclaimer was “also absent from [Rothschild’s] METABIRKINS social media accounts and Discord channel, where the METABIRKINS NFTs are prominently advertised.”

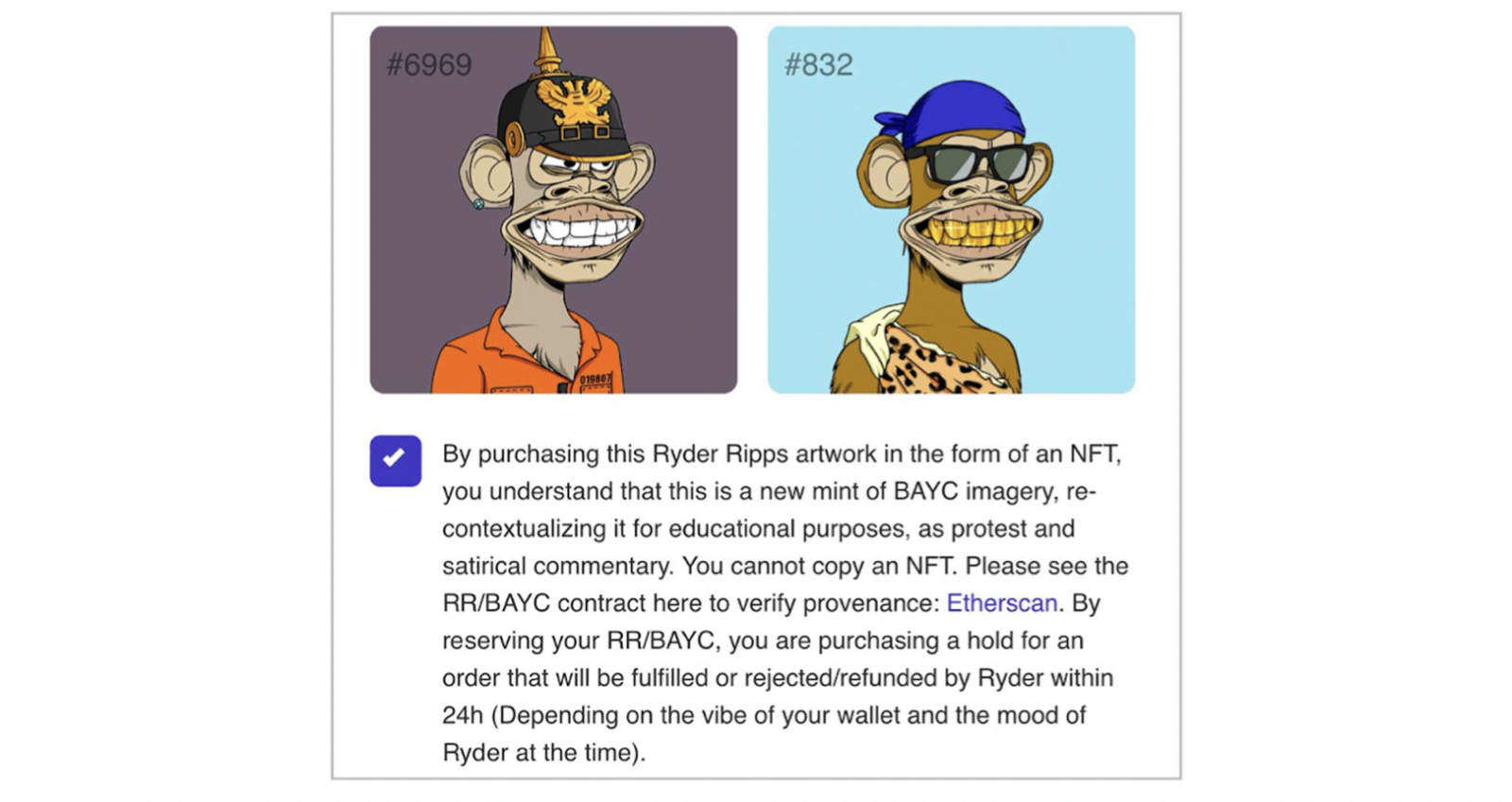

Disclosures similarly proved to be a relevant issue in Yuga Labs v. Ryder Ripps, another trademark-centric case that stemmed from the offering and sale of NFTs. In that case, C.D. Cal. Judge John Walter focused his attention on the disclaimer on artist Ryder Ripps’ website, which stated that Ripps is the creator of the RR/BAYC NFTs and that the project uses “satire and appropriation” to criticize Yuga Labs’s Bored Ape Yacht Club collection. Although Ripps and his fellow defendants argued that the disclaimer “negates any confusion,” Judge Walter held that the lack of consistent use of the disclaimer across all sites on which the RR/BAYC NFTs were marketed and sold was problematic.

Moreover, the court held that “the fact that the defendants felt obliged to include a disclaimer demonstrates their awareness that their use of the BAYC marks was misleading.”

Still yet, in a decision back in 2012, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California determined that in some instances, even well-worded and consistently-used disclosures may not be enough to save a defendant from trademark liability. In Rolex Watch, USA v. Agarwal, the court found that the trademark-bearing Rolex watches that were being offered up by the defendants had been modified so heavily that the use of a disclaimer would not change the result. Since the modified watches were essentially “new products,” the court held that a disclaimer that the product contains replacement parts would still cause confusion among consumers.

It is not yet obvious what stance the court in Chanel v. WGACA will take when it comes to disclaimers, but what is clear is that trademark holders’ quests for the adoption of broad disclaimers have not come without pushback, including in the Chanel case.

In response to Chanel’s injunction bid, WGACA has argued that there is “no need for the over-the-top additional disclaimer that Chanel would impose, which would violate WGACA’s First Amendment rights by compelling speech.” And even if the court determines that a disclaimer is necessary, counsel for WGACA asserts that the language in Chanel’s proposed disclaimer “goes well beyond what is ‘reasonably necessary’ to prevent any likelihood of confusion” and instead, is “clearly intended to discourage any purchaser and disparage WGACA.”