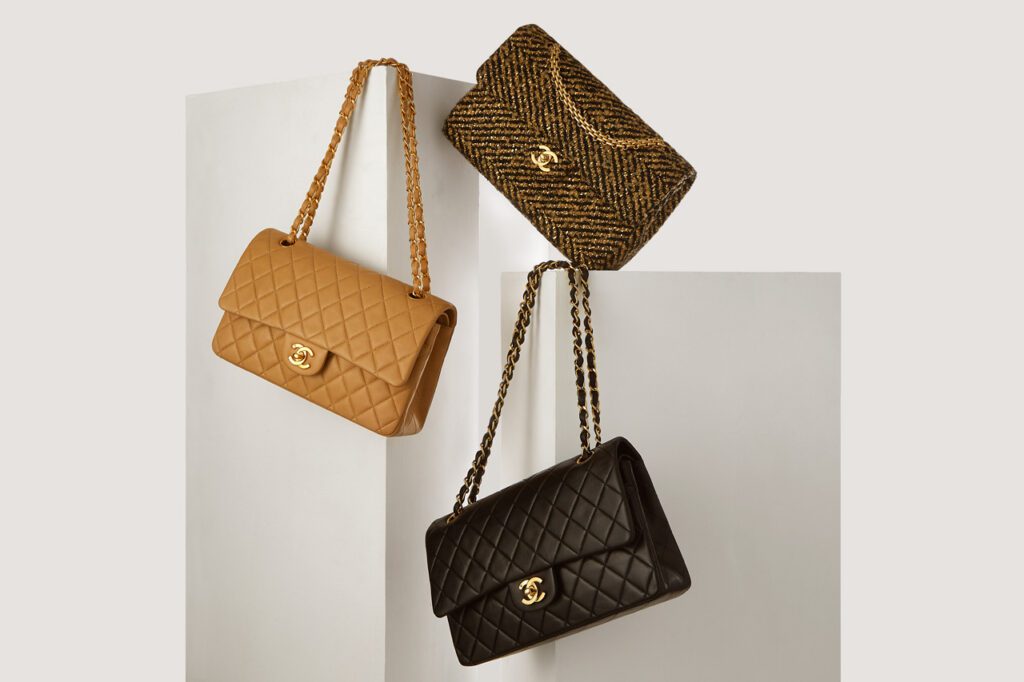

What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”) is angling to avoid a broad injunction that would prevent it from continuing to make use of Chanel’s trademarks in connection with its sale of pre-owned products, advertising Chanel products that have not been authorized for sale by Chanel, and offering up Chanel goods that have been materially altered. On the heels of Chanel lodging a motion for a permanent injunction last month, as first reported by TFL, counsel for WGACA argues in a new trial brief that Chanel’s proposed injunction should be rejected because it is “overbroad” but also because Chanel has not been harmed by its resale of Chanel branded products.

Some Background: On the heels of the parties’ trial earlier this year, a New York federal jury sided with Chanel, finding that WGACA is liable for: (1) willful trademark infringement, false association and unfair competition based upon its unauthorized use of Chanel’s trademarks and other indicia of Chanel; (2) willful trademark infringement based upon its creation and use of various hashtags containing “Chanel” or “Coco Chanel” to advertise and market products on social media; (3) willful trademark infringement based upon its sale and offering for sale of non-genuine CHANEL-branded products; (4) willful trademark infringement based upon its sale of counterfeit CHANEL-branded products; (5) and willfully engaging in false advertising.

As part of the second phase of the proceedings, Chanel is seeking a sweeping injunction to permanently bar WGACA from using its trademarks in connection with its unauthorized advertising and sale of CHANEL-branded, among other things.

Lack of Harm & Willfulness

At a high level, WGACA argues in its newly filed brief (as first reported by TFL) that Chanel’s bid for a preliminary injunction should be denied on the basis that Chanel has not been harmed, let alone irreparably harmed, as a result of its activities. In particular, WGACA claims that Chanel “offered no evidence of loss and this court already found that [it] failed to offer any evidence of lost sales.” At the same time, WGACA asserts that Chanel’s failure to prove actual confusion among consumers as to the source of its Chanel offerings and/or any connection between it and Chanel “suggests that there is no threat of future confusion that needs to be addressed” by way of injunctive relief.

WGACA further aims to chip away at Chanel’s quest for broad injunctive relief by arguing that the legal remedy at play (namely, the $4 million in statutory damages awarded to Chanel “for its claim for trademark infringement based on WGACA’s sale or offering for sale of Chanel-branded handbags bearing counterfeit trademarks”) has already adequately compensated Chanel. The reseller takes issue with Chanel’s claim that the legal remedies at play are inadequate in light of the jury’s finding that WGACA acted willfully and thus, will continue to engage in the wrongful activity at issue unless stopped by way of an injunctive relief. Pushing back here, WGACA argues that despite the jury’s verdict, the evidence in the case actually establishes that it did not act willfully.

On the willfulness front, WGACA contends that it is undisputed that it “was ignorant of” the allegedly infringing or counterfeit nature of an array of the Chanel products it offered up for sale, including bags that bore serial numbers that had been stolen from a Chanel supplier factory in Italy in 2012, until Chanel shed light on these issues during the case at hand. WGACA claims that it was also unaware of “Chanel’s prohibition of the sale or distribution of … point of sale items until this litigation,” and that “these facts, in and of themselves, rebut any claim of bad faith and willful conduct.” Had Chanel made this information available to retailers in the second-hand market, “the circumstances surrounding the sale of these items could have been avoided,” per WGACA.

Chanel’s “Unclean Hands”

In what might be the most interesting aspect of WGACA’s brief is its argument that the injunction should be denied because of Chanel’s unclean hands. (In accordance with the doctrine of unclean hands, a court’s “the equitable powers can never be exerted on behalf of one who has acted fraudulently, or who by deceit or any unfair means has gained an advantage.”)

In addition to taking issue with “false” testimony provided by one of Chanel’s key witnesses and Chanel’s alleged efforts to prevent at least one of WGACA’s witnesses from testifying at trial, which show that the brand has unclean hands, WGACA argues that Chanel is really seeking injunctive relief in an aim to accomplish the “improper, anticompetitive goal” of restricting sales in the secondary market.

“The radical injunction proposed by Chanel is nothing more than a transparent attempt to wrest control of the secondary market, a plan that Chanel has been contemplating since at least 2017,” WGACA argues in furtherance of its unclean hands claim, noting that instead of engaging in the secondary market, “Chanel chose to attack the secondary market as is evident by its initiation of lawsuits against WGACA and The ReaReal in 2018.”

WGACA claims that Chanel further engaged in “inequitable and bad faith conduct” by filing three complaints against it in this case in 2018, in which it accused the reseller of counterfeiting, despite lacking evidence that WGACA had, in fact, engaged in counterfeiting. According to WGACA, only after gaining access to certain WGACA records a couple of years later in 2020 (and discovering “a few dozen supposedly problematic bags out of over 70,000 items”) did it have the basis for its counterfeiting claims, thereby, making “the entire premise of the counterfeiting case brought in 2018 … an admitted fiction.”

A More Limited Injunction

If the court does determine that a permanent injunction is necessary in this case, WGACA argues that it should reject Chanel’s proposed injunction because it is “impermissibly overbroad and overreaching,” particularly as “the evidence establishes that WGACA acted in good faith and built its reputation and success by establishing itself as a trustworthy purveyor of authentic luxury items.” The reseller asserts that the “extreme injunction proposed by Chanel goes far beyond what is necessary and is clearly intended to terminate WGACA’s ability to sell any Chanel goods.”

Specifically, WGACA contends that requiring it to abide by the terms Chanel’s proposed injunction “would not only devastate [its] business, but would chill the second-hand industry as a whole,” the company contends, but would violate WGACA’s First Amendment rights to engage in lawful, truthful commercial speech. Reflecting on the First Amendment, WGACA argues, among other things, that a “litany of restrictions” in Chanel’s proposed injunction seek to “limit WGACA from advertising Chanel products in any context,” going so far as to prevent WGACA from “using the Chanel mark to advertise its ‘general business’ thereby precluding WGACA from even advising the public that it has Chanel products for sale—lawful commercial speech protected by the First Amendment.”

Additionally, Chanel aims to prohibit WGACA from advertising, offering for sale, or selling any CHANEL-branded items without first obtaining permission from authorized personnel at Chanel or having documentary evidence that the item was first sold by Chanel. “It is commercially untenable to expect WGACA to obtain the original proof of purchase from every source of the vintage items it obtains, [as] Chanel customers from years ago cannot be expected to have saved all receipts for their purchase of Chanel handbags or other items, and to have them available when they choose to sell or pass on the items,” the reseller asserts.

Moreover, there is no justification for this proposed requirement, WGACA argues, claiming that it “would completely undermine WGACA’s entire business and create a logistical morass forcing WGACA to regularly seek permission from a hostile actor intent on ending WGACA’s second-hand sales of Chanel all together.”

The case is Chanel, Inc. v. What Goes Around Comes Around, LLC, et al., 1:18-cv-02253 (SDNY).