Luxury resale is contentious business. According to Chanel, which filed a strongly-worded lawsuit against What Goes Around Comes Around in March and another against The RealReal in November, at least some of the significant array of second-hand Chanel good being peddled are fake. Maybe even more troubling for the 109-year old Paris-based brand: The way in which the luxury resellers are allegedly piggybacking on the reputation and appeal of Chanel, one of the most esteemed fashion houses in the world, for its own financial gain.

The lawsuits, which are currently underway in federal court in New York, shed light on the still-largely-unsettled relationship between luxury brands and resale companies. They also serve to boldly embody what no shortage of luxury brands have voiced concerns about behind the scenes.

To date, “the fear” amongst fashion’s well-established houses “is that we’re cannibalizing their business,” Julie Wainwright, the founder and CEO of The RealReal, told WWD last October. Wainwright further held that she suspects brands “might not like [resellers] because maybe they’re not at all comfortable with their products being sold online.” And dislike luxury resale, many brands do. As Wainwright, for one, told TechCrunch last year, at least one brand whose name “begins with a C” is particularly unhappy with the likes of The RealReal, which stocks ready-to-wear from Gucci, Givenchy, Chloe, Louis Vuitton, and Celine; jewelry and watches from Chanel, Lanvin and Valentino; Cartier and Bulgari, and Rolex and Patek Philippe, among others, and recently began offering menswear.

Yet, despite this enduring animosity, the Chanel lawsuits are striking in large part because resale companies have been able to live a relatively lawsuit-free existence. This is because the straightforward resale of luxury goods falls squarely within the bounds of the law. The First Sale Doctrine states that once a trademark owner, such as Chanel, releases its goods into the market, it cannot prevent the subsequent re-sale of those goods by their purchasers, assuming, of course, that the physical condition of the goods in question had been altered or impaired..

However, from the outset, fashion brands have alleged that there is more at play than individuals merely reselling their used handbags. As Chanel alleges in its recently-filed lawsuits, the resale business model relies heavily on the leveraging of the appeal and esteem of the world’s most famous luxury brands and their valuable intellectual property, including brands’ trademark-protected names and logos, which fashion’s most established brands have spent over a century and hundreds-of-millions (if not billions) of dollars in marketing costs and legal fees to establish and maintain.

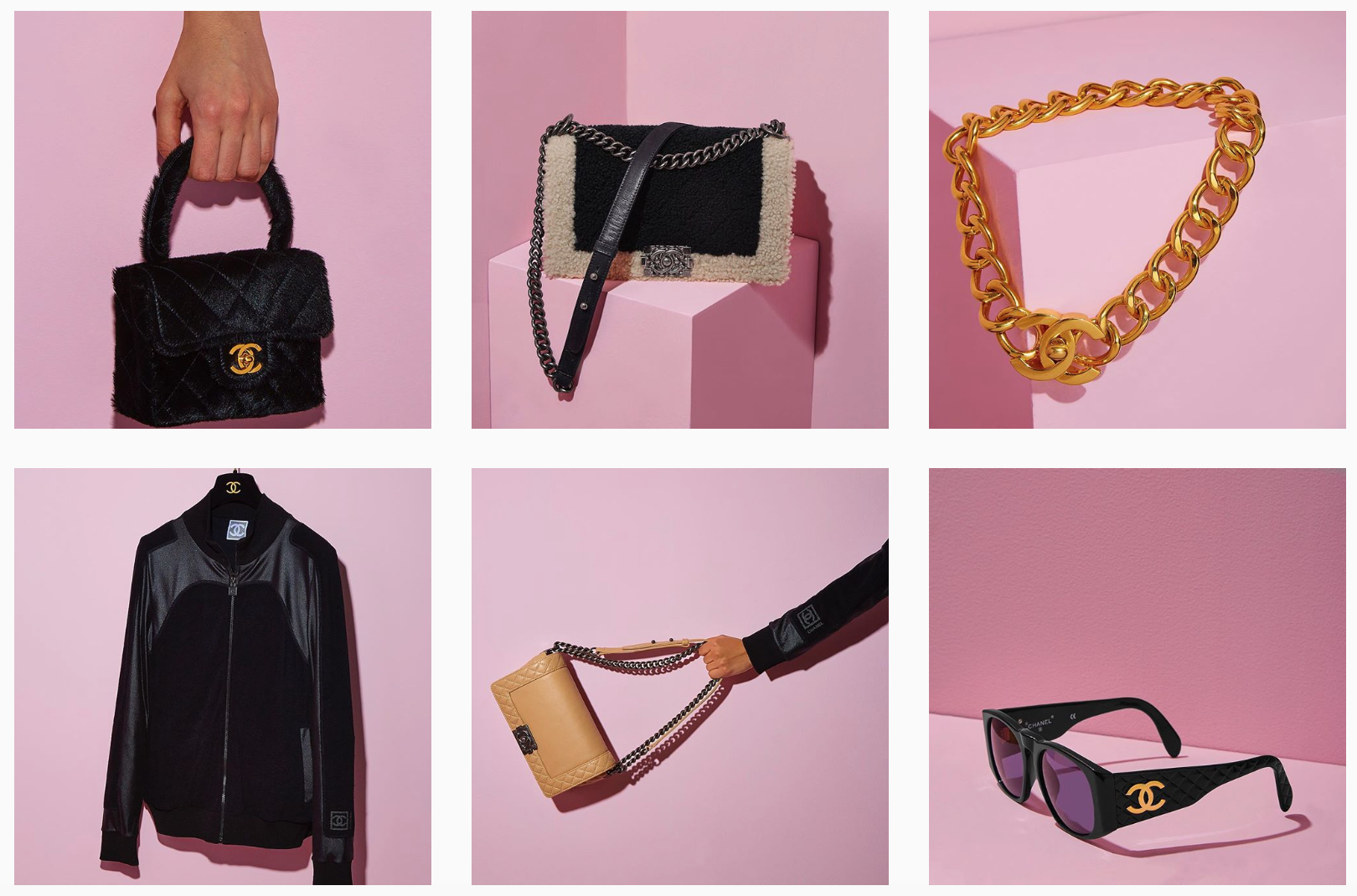

According to Chanel, this overreach by resale sites includes them “posting images and content exclusively associated with Chanel” in an attempt to create an association in consumers’ minds. It also involves them “making repeated and unnecessary use of Chanel’s famous trademarks” on their websites and social media accounts in order to lure in consumers, who might think the parties are in some way affiliated when they are not.

Despite the ugly picture painted by Chanel’s lawsuits of a war between the old guard and the resale newbies, Wainwright claims that the status quo is changing, whether brands like it or not. Luxury and the brands that are most closely tied to it, she says, are “going through an evolution. Our first year, I heard [the brands] hated us. Now, they’re keen to find a way to work together. They’ve realized they can maybe learn something from our data.”

Wainwright said earlier this year that she has met with “all the top brands,” telling them that The RealReal – which she insists is a valuable member of the luxury goods community – is “the gateway drug to their brands,” and as a result, can be an asset to them, rather than a threat. For instance, “The data the company collects gives them the ability to track brands by age and over time.”

The RealReal has since revealed that it does, in fact, partner with brands in a few different ways, everything from the simple sharing of resale data to consignment partnerships and promotional relationships with like-minded brands around a shared mission.” A spokesman for at least one major fashion player, Kering, the Paris-based parent company of Gucci, Balenciaga, Saint Laurent, and Bottega Veneta, among other brands, revealed in an earnings call this spring that it is “collaborating actively with [The RealReal],” which likely explains the wide variety of “new w/ tags” Gucci sunglasses being offered on the site and the slew of “new w/ tags” Bottega Veneta dresses, wallets, and footwear, etc.

The notion that luxury and resale are not mutually exclusive but instead, are more aptly described as allies has been echoed by Sébastien Fabre, CEO of Vestiaire Collective, who has said that resale is “a point of entry-level access for young customers who can’t yet shop full price luxury.” Similarly, Tracy DiNunzio, CEO of Tradesy, has noticed a similar pattern: “The resale market leads to customers making more purchases at retail. When a customer knows she can resell her item, she’s going to be willing to pay a little more for it.”

And still yet, Wainwright insists that new and resale purchases are not mutually exclusive. “We find people are buying both new and previously owned,” she explains. “Americans are value shoppers more than anything. So, we find they buy from our site and buy new and then consign things they may have kept for a couple of months. Then they use the money from consignments to buy new or buy from us again.”

Yet, as indicated by Chanel’s suits, which argues that What Goes Around Comes Around and The RealReal are actively attempting to “deceive or mislead consumers,” this is still an area of the market that is widely contentious and only set to grow more so.

As for the lawsuit that Chanel filed against The RealReal, which the e-commerce site has characterized as “a thinly-veiled effort to stop consumers from reselling their authentic used goods, and to prevent customers from buying those goods at discounted prices,” it is only expected to get uglier. (This is particularly true since Chanel is making an arguably obvious bid to chip away at consumer trust for the popular e-commerce site by planting the seed in consumers’ minds that TheRealReal inventory is rife with fakes).