Square’s $29 billion acquisition of buy now, pay later (“BNPL”) pioneer Afterpay Ltd. is the latest in a string of bold signals that the BNPL market is booming, and more growth is on the horizon. The biggest deal to date for Square, the payment services company started by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey, the Afterpay acquisition comes on the heels of fellow BNPL player Klarna raising $640 million in June, bringing its valuation of the 16-year-old company to a cool $46 billion, a figure that many media outlets were quick to note, is higher than an array of Europe’s largest banks, including Barclays and Credit Suisse Group.

Such burgeoning attention to BNPL makes sense given that American consumers, alone, spent an estimated $20 billion to $25 billion in 2020 by way of deferred payments, such as those offered by Afterpay, as well as its competitors Klarna and Affirm, according to a March report by analytics firm CB Insights. To put the rise of BNPL into perspective even further, Klara’s services, for instance, are used by more than 1,030 brands – from LVMH-owned Givenchy to Chinese fast fashion mega-retailer Shein, and as of December 2020, were being used by 3.5 million monthly active users, an increase of 204 percent year-over-year.

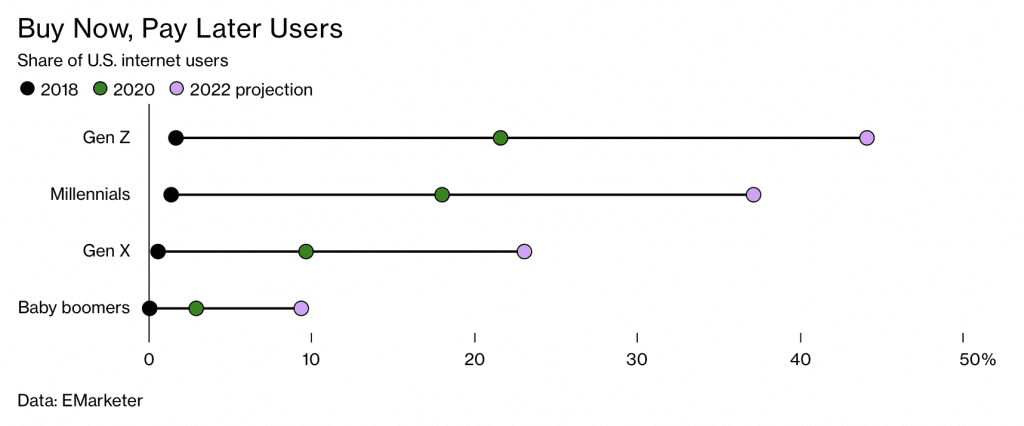

Meanwhile, a joint Credit Karma/Qualtrics survey found early this year that 42 percent of American consumers have used BNPL at least once, noting that BNPL is not a new concept, and yet, “over the past few years, fintech companies have sprung up offering BNPL services all over virtual checkouts or in apps in a fresh way,” helping to attract younger consumers, namely, Gen-Zers – and a lot of them. And the numbers at play are on the rise. “Worldwide, the CB Insights report projects that transactions through such plans could grow 10 to 15 times by 2025, topping $1 trillion,” per Bloomberg, which notes that BNLP’s “penetration in the U.S. may be 3 percent of e-commerce, but there’s room to grow – it is about 10 percent in Australia.”

The mainstreaming of BNPL services – which enable consumers to buy their products now and pay for them later often via smaller, by way of smaller payments spread out over a few weeks or months, often without interest – is expected lead to consolidation. The Sqaure deal, for instance, is likely to “pave the way for more acquisitions, with Mastercard, Visa, PayPal Holdings, and others showing interest” in the space, Christopher Brendler, an analyst with brokerage group D.A. Davidson, told Reuters, and the likes of Apple reportedly looking to add similar deferred payment processing options to its existing Apple Pay platform.

Enter: Regulators

At the same time as the number of brands, users, and dollars in the BNPL arena continues to grow, the largely unregulated nature of the BNPL explosion has been garnering the attention of regulators around the world. In June, the U.S. government’s Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”), for one, published a blog post, entitled, “Should you buy now and pay later?”, in which it highlighted some of the differences between BNPL operations and those of traditional credit card companies and other consumer loan lenders.” The government agency noted that BNPL companies “generally do not conduct a hard credit inquiry when you apply,” and instead, most BNPL providers only require users to be at least 18 years old, have a mobile phone number and a debit or credit card to make payments, and to validate their identity.

In an effort to educate consumers, the CFPB also highlighted the fact that “BNPL loans currently lack the consumer protections that apply to credit cards,” and noted that while many BNPL companies notably do not charge interest – a key selling point for using such services, “most do charge late fees if you miss a payment.”

The CFPB’s article comes as the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) is “expanding the use of the Restore Online Shoppers’ Confidence Act of 2010 to target online sellers for failing to disclose all material terms and obtain informed consent from consumers before charging them for products and services,” according to Sheppard Mullin’s Moorari Shah and A.J. Dhaliwal, who state that companies doing business online, including in the BNPL space, “would be well-advised to review the CFPB’s and FTC’s guidance to ensure that their business practices do not run afoul of regulatory expectations.”

Still yet, such efforts follow from actions from the California Department for Business Oversight (“DBO”), a division of the state government that regulates financial services, which has taken on a number of cases centering on BNPL services. In one such case, the DBO reached a settlement with Afterpay in March 2020, after accusing the BNPL leader of collecting fees from more than 640,000 Californians in so-called BNPL transactions that were actually “illegal loans.” As a result of the settlement, Afterpay was required to refund $900,000 to consumers and pay $90,000 in administrative fees. A company spokeswoman stated in connection with the settlement last year that “Afterpay does not believe such an arrangement required a license from the DBO or was illegal, [but] has agreed to conduct its operations under the DBO license as a part of this settlement.”

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, for example, the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) revealed in the Business Plan that it released in July that among its top priorities for the next year are “ensuring that consumer credit markets work well,” which Gowling WLG attorneys Ian Mason, Sushil Kuner and Kam Dhillon say includes “reviewing consumer credit in areas, such as the BNPL sector.” Early this year, the FCA recommended that all BNPL credit arrangements should be brought within the scope of the UK’s regulatory regime for consumer credit – and thus, subjected to the same regulations as more traditional creditors – “as a matter of urgency,” as many BNPL arrangements, when structured in a certain way, fall outside the scope of regulation.

The Ethics at Issue

All the while, BNPL has faced pushback from critics, who suggest that the system puts spenders – especially younger ones – at risk of overextending their finances. “By offering goods immediately, and delaying the pain of parting with any money, BNPL lenders exploit the human tendency to undervalue future losses and overvalue present satisfaction – which is known as present bias,” Joshua Hobbs, a lecturer and consultant in Applied Ethics at the University of Leeds, argues, noting that research shows that “this bias increases in response to instability and stress, raising the worry that such services disproportionately target consumers who are already vulnerable.”

More clearly – and uniformly – defining what BNPL services consists of – as “some digital purchase installment loans are for just a few weeks; others can be for years; some are for small-dollar purchases of ephemera, others for expensive durable good,” the Wall Street Journal reported early this year – will, in fact, help to protect consumers, as will treating BNPL lenders in the same way as other financial institutions. However, Hobbs argues that what is really needed is “regulation sensitive to the unique nature of these lenders, their services, and the risks” that are at play. In light of the “unique ethical risks involved,” he says that regulators need to place “a duty [on BNPL providers] to inform customers of the psychological biases that these services take advantage of (unwittingly or otherwise), to help consumers to make rational financial decisions.”