image: R29

image: R29

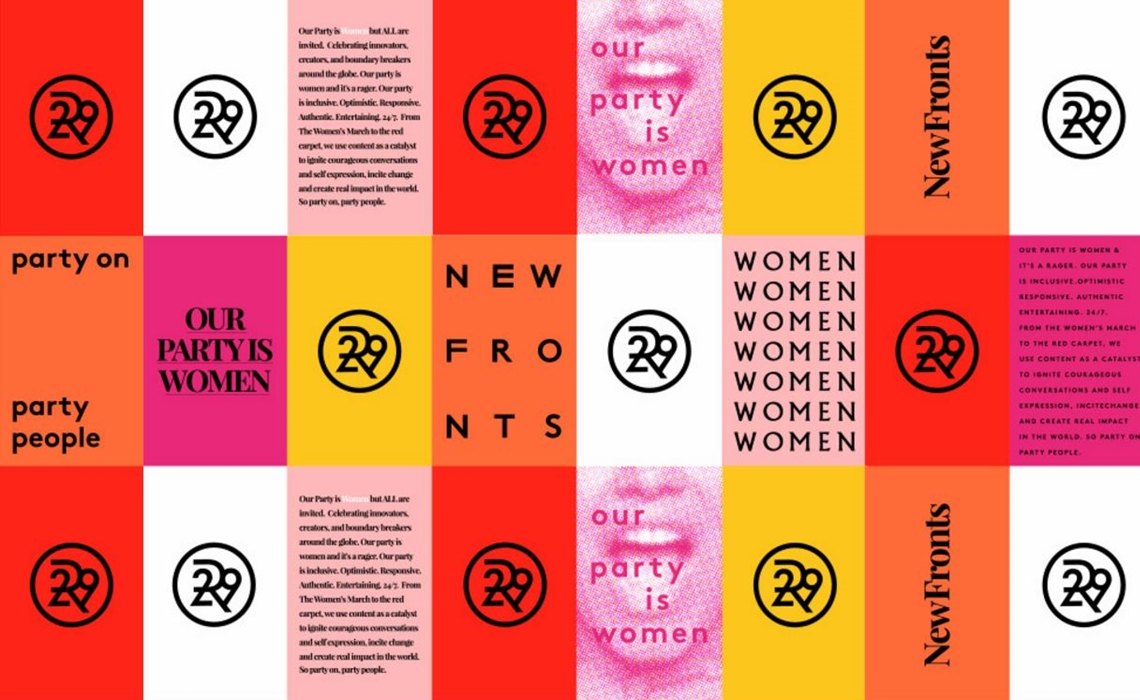

Refinery29 is doing something very interesting. The $500 million New York-based media company – which runs Refinery29 and its various “dedicated franchises” – is blurring the already hazy line between church and state when it comes to advertising. The 13-year old company has long partnered with fashion entities to provide them with branded content by way of its in-house content studio (a common industry money-maker), but the site is upping the ante and potentially crossing the line by combining the roles of the editorial and marketing staff, and “giving its editorial staff the chance to operate like influencers,” according to Digiday.

Change has been creeping up in recent years as a result of the widespread reliance on influencer marketing by fashion and other consumer goods companies. Brands began “indicating that they would like ways to be closer to Refinery29’s editorial staffers,” R29’s chief content officer Amy Emmerich told Digiday. And so, the media company decided to deliver.

This has included a handful of initiatives, including one that the publication calls “Refinery Pop-Ins.” These “Pop-Ins” – which Digiday characterizes as R29 “selling advertisers the opportunity to set up shop inside its offices” – give brands the chance to market their wares directly to R29’s editorial staffers, almost certainly in hopes that those products either land in an R29 article or editorial … or on the Instagram pages of the site’s many influencer staffers.

Refinery29 offers brands access to its staff of highly-followed Instagram individuals in other ways, too. What might be the most controversial tactic comes by way of R29’s positioning of its editorial staff as influencers that are available to post endorsements on behalf of advertisers.

For example, writes Digiday’s Max Willens, “This past fall, to promote a program created with Walgreens, a number of [Refinery29] editorial staffers created sponsored posts on Instagram promoting the effort.” The posts at issue, per Digiday, were, in fact, “Federal Trade Commission compliant,” meaning that they included proper language indicating that the posts were paid for.

Companies, such as Google, have relied upon Refinery29 editorial staffers, including those with notable social followings, to publish sponsored content, as well. One such editor/influencer Annie Georgia Greenberg, who serves as R29’s Fashion editor at large and boasts 23.9k Instagram followers, posted Google-sponsored ads to her Instagram account, along with content from the likes of ASOS, Under Armour, TBS, Village Luxe, and Nordstrom, among other brands/retailers. (It is not clear which – if any – are directly tied to Refinery 29).

image: @theagg

image: @theagg

Other R29 “influencers,” so to speak, include “features writers, video producers, and R29’s video talent,” who, per Digiday, “participate completely of their own volition, and are compensated in the form of a quarterly bonus in their paychecks.”

Since the Federal Trade Commission requires that “material connections” of nearly any kind be disclosed in connection with sponsored content and endorsements even when those endorsements are not the result of compensation (i.e., if the individual is in some way connected to the brand she is endorsing by way of, say, a familial or employment relationship), the R29 content at play clearly falls within the realm of #ad, and in many (although not all) cases, the sponsored posts by R29’s staffers are properly disclosed in accordance with the FTC’s stringent guidelines.

But looking beyond FTC considerations, the most interesting element here is the fashion industry’s larger (and in the case of R29, rather straightforward) obliteration of the line between independent editorial staff and the advertiser-pleasing marketing department.

Yes, the fascinating thing here is that publications, including R29, as well as Conde Nast and Mental Floss (which have also used their editorial teams to create branded content, per Digiday), are opting, in at least some cases, to dissolve the divide between branded and un-branded content. With this type of arrangement comes the very real risk of bias (by way of favorable treatment for brands), especially in light of Digiday’s proposition that R29 is actively using its editorial staff (aka editor-influencers) to lure in advertisers.

In terms of prospective bias, the integration of branded content into the daily workings of the site’s editorial staff (which are, at least, in theory, supposed to put forth content independent of advertiser concerns), as opposed to having it squarely within the bounds of Refinery29’s separate content studio (as was the case in the past, per Digiday), could arguably create complications. In particular, it could lead to an overarching incentive to feature brands (or unduly favor brands) to further drive ad revenue. (Please note: This is something that big-name print magazines have been well-known to do for decades).

This risk is paired with the increasingly fluid use of R29 staffers’ accounts as extensions of the R29 platform for the dissemination of the site’s content and for advertising purposes, which is both a smart marketing tactic and maybe a deceptive and maybe even, unethical, move.

Given an array of recent research, including a study conducted in collaboration with the Associated Press, social media users are more likely to interact with and share posts from someone other than the original author or website of origin. With this in mind, providing advertisers with the chance to place ads on individual staffers’ accounts is undoubtedly smart and effective strategy. But, it maybe also be a deceptive strategy on behalf of the the parties involved. If for no other reason, this strategic placement undoubtedly creates an initial impression that a post is somehow more authentic or objective than if it were on R29’s larger, more corporatized account.

While the strategy of pairing sponsored content with R29’s influencer editors is likely resulting in higher levels of engagement than if it were posted exclusively on R29’s site, this practice does give rise to questions of appropriateness and/or ethics bearing in mind the possible lack of transparency in terms of objective editorial content and potentially-comprised advertorial overlap.

As for how this advertising content is being received: One media agency source who is responsible for handling clients’ branded content, told Digiday, “It’s something we expect users to push back a little bit more on, and they don’t. It’s super exciting.”

It seems that readers are either untroubled by the bed-sharing of editorial and advertising, which, if true, would not be terribly surprising considering the current landscape of fashion advertising, in which brands take editors on trips and publications are known to favor brands that advertise on their pages and websites. Or … readers simply are not up to speed on the complicated innerworkings of this new advertising model. And to be frank, save for Digiday’s revealing article, how would they be?

A representative for R29 did not respond to a request for comment.