With an estimated value of $800 billion by 2024 and the potential to ultimately generate $1 trillion in revenue by JP Morgan’s calculations, the metaverse is being characterized as the “New Internet” and an innovative medium for brands to connect with consumers. Still relatively new, consumers and companies, alike, are experimenting with engagement across various platforms, including Decentraland, The Sandbox, and Roblox. And the latter are looking to connect with consumers and generate commercial value, as platforms like Roblox have reportedly attracted nearly 50 million daily active users and offered up more than 5.8 billion branded virtual items – both via sales and free giveaways – in the process.

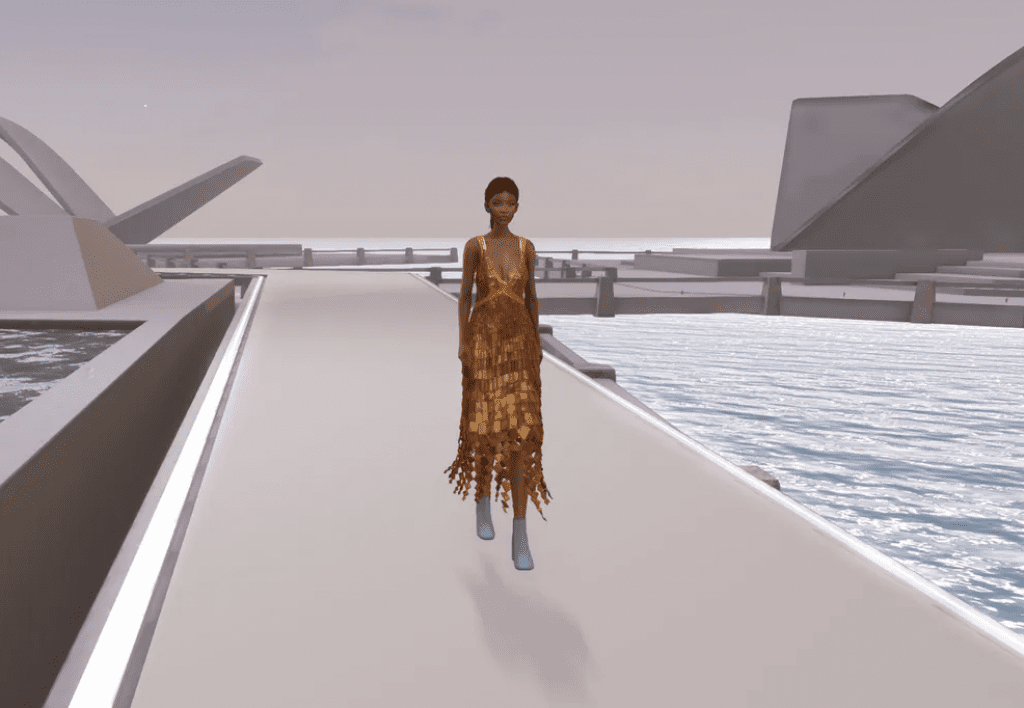

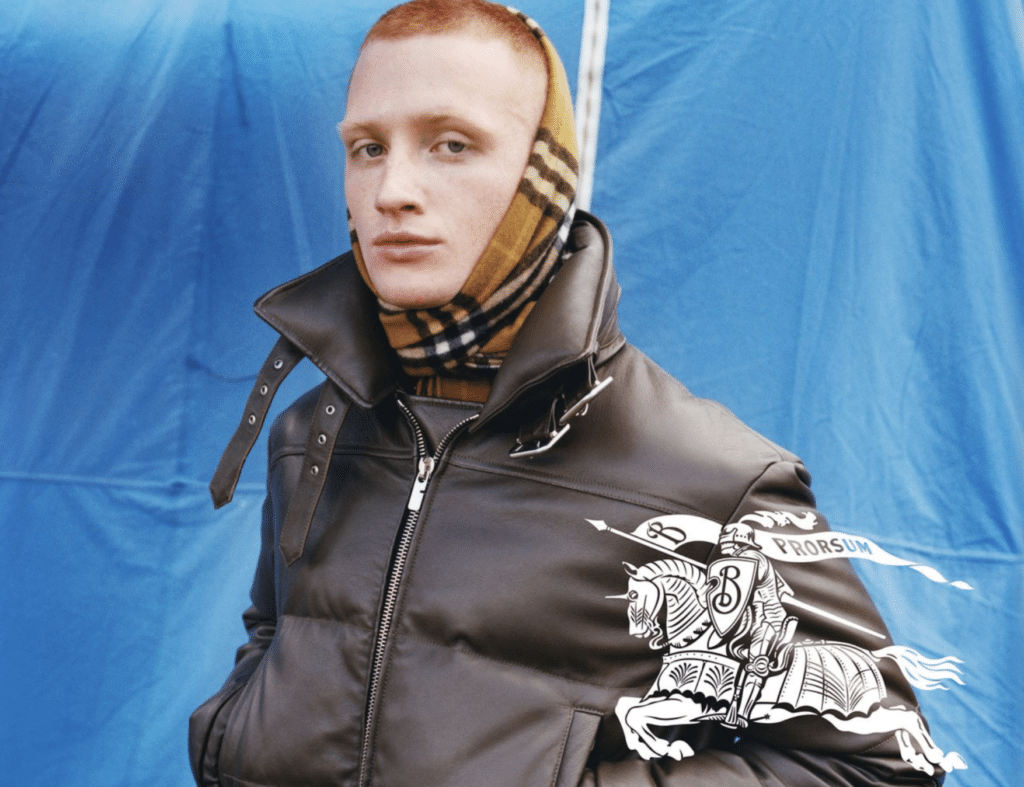

Enabled by virtual and augmented reality technologies, consumers can interact with brands in a various ways in the metaverse, such as through virtual concept stores, as well as runway shows and sports and musical events. For example, Decentraland’s Metaverse Fashion Week, which took place in March 2022 and included designs from the likes of Jonathan Simkhai, Dolce & Gabbana, Paco Rabanne, Elie Saab, Tommy Hilfiger, Etro, and Dundas, among others, received more industry attention than any previous digital fashion event. Beyond fashion, IKEA’s “Studio” allows shoppers to visualize how products look in their homes, and brands like iTechArt and Oculus VR, which produce VR headsets for immersive use in digital spaces, aim to improve user experience and to encourage experiences like that of IKEA.

At the same time, non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”) have gained mainstream attention as digital assets, despite volatility in the crypto market, with some commanding higher prices than the physical equivalent. And still yet, even governments have jumped on board the metaverse bandwagon, with Seoul’s metropolitan government planning to build a 3.9 billion-won metaverse platform to allow citizens to access public services virtually. In Thailand, the Tourism Authority launched the Amazing Thailand Metaverse for tourists to explore virtual durian orchards, and collect NFTs that can be used in the “real world.”

With inflationary pressures in 2022 and wild fluctuations in cryptocurrencies, some may ask if interest in the metaverse and NFTs is sustainable in the short to medium term. In the longer term, if public services and infrastructure improves, allowing for more everyday users, then more brands beyond the fashion, cosmetic or sports segments (which have been among some of the earliest and most enthusiastic adopters) can follow suit with endeavors of their own aimed at connecting with consumers as part of an economy that McKinsey projects could be worth a whopping $5 trillion by 2030.

Control and Jurisdiction in the Metaverse

As brands are deciding their intellectual property strategy in anticipation of entering into a metaverse venture, some of the preliminary questions worth considering center on issues of control and jurisdiction, namely, who has control of the metaverse at issue and which jurisdictions are relevant? With regards to control, the more control an organizing entity (potentially such as Meta in Horizon Worlds), the more likely policies, such as notice and takedown mechanisms, will be in place to enforce against trademark and/or copyright infringement. In contrast, there are decentralized metaverse platforms, such as Decentraland, which is owned by users and governed by a decentralized autonomous organization. These platforms are devoid of single ownership, which may make it difficult to formulate – and enforce – policies that allow brand owners to participate while also ensuring that their intellectual property is protected.

Will the metaverse of the future be a single, digital universe? A user ideally should be able to travel between the Meta version of the metaverse into the Microsoft version seamlessly and so on – with assets and information flowing freely between platforms. The notion of interoperability is a core tenet of the metaverse, which is expected to function something like the Internet today – albeit without boundaries. Against this background, the question becomes: how can brands protect themselves in this new single digital environment? Will brands be offered a single takedown mechanism for the whole metaverse? And which service providers will be responsible for the potential infringing actions taking place in the metaverse?

Currently, some platforms have takedown mechanisms for enforcement against infringement. NFT marketplace OpenSea, for instance, maintains a system in furtherance of which it removes listings based on brand owners’ infringement complaints. However (and thanks to the nature of NFTs, which are immutably recorded on the blockchain), an individual may continue to offer up the allegedly infringing NFTs (and any digital assets tied to those NFTs) on other platforms.

This reality also raises questions from a jurisdiction perspective. For instance, if a brand owner can identify the infringer and their home country, would a traditional court action be possible in that country? (Based on a growing number of existing infringement lawsuits, that answer seems to be a straightforward yes.) In addition, can brand owners successfully pursue the owner(s) or controller(s) of a metaverse for intermediary liability? And if so, what is the appropriate jurisdiction? These are just a few of the many questions to be considered by brand owners at the moment.

Brands in the Metaverse

Another question that brand owners current face is whether they can simply rely on existing trademark rights when it comes to enforcement in the metaverse and thus, avoid lodging separate applications for virtual goods and services? While there are ongoing infringement cases in the U.S. in which companies rely on their “real world” trademark rights to claim infringement in connection with NFTs and early iterations of the metaverse, there is still no clear decision in many jurisdictions. Although there is an argument that with the blurring of the physical and digital space, companies should be able to rely on existing rights. Despite (or maybe due to) such uncertainty, there has been an increase in metaverse related filings across the globe.

In February 2022, 16,000 Chinese applications for trademarks containing “METAVERSE” or “元宇宙” (YUAN YU ZHOU, which is “metaverse” in Chinese) had been filed in every class of goods/services. The China National Intellectual Property Administration has taken a clear stance against abuse of the registration of marks containing such terms and is only allowing for trademarks with “real” world distinctiveness equivalent to that in virtual world for registration to protect such interests in the metaverse.

Meanwhile, in the United States, upwards of 4,000 NFT-related trademark applications for registration were filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office between January 1 and May 31, 2022. And the European Union Intellectual Property Office has seen similar increase in new applications filed in 2022 –football club Inter Milan, luxury sports car maker Maserati, and energy drink brand Red Bull are among the companies that have filed applications related to NFTs and/or the metaverse.

Such metaverse-focused applications are typically filed in class 9 for “downloadable virtual goods including NFTs”, class 35 for “retail stores for virtual goods”, and/or class 41 for “entertainment services in virtual environments.” Depending on the level of brand engagement, broader protection may also cover class 36 for financial services relating to virtual currencies, class 38 for telecommunication services in relation to virtual communities, class 42 for non-downloadable computer software for virtual goods creation/trade in NFTs.

With the rise in metaverse related filings, at least some local trademark offices are also reviewing and updating the new classification of goods and services. For example, in Thailand, the Trademarks Office Guidelines has been updated to reflect some of these new terms and in practice the Vietnam Trademarks Office has also accepted such specification. On the other hand, in Indonesia, metaverse related goods and services are not yet standard items, and therefore, one option is to try and fit the terms into locally accepted specifications until new specifications are made locally. In China, as long as a brand’s Chinese national registration covers all the subclasses of traditional goods and services that align with the relevant metaverse classes, this should provide sufficient coverage without incurring extra costs from new filings.

Generally, for a brand to future-proof their trademark portfolio, it may make sense to extend trademark rights in (and registrations for) key business markets and/or where the intellectual property enforcement regime may not be as developed such that you would need to rely on trademark registration for specific virtual specification. Brand owners should also continue to actively consider protection for 3D shape marks, sound marks (i.e., MP3), holograms, motion marks, and multimedia marks, as these may be more relevant in the audio-visual sensory environment of the metaverse.

Brands will no doubt be keen on watching future developments in the metaverse and ensure their intellectual property is adequately protected. Having the correct strategy in place will be crucial for any brand looking to thrive in the “New Internet” and exercise brand control.

Lisa Yong is a Principal in Rouse’s Indonesia office with extensive intellectual property experience in South East Asia.

Love Fält is a Senior Associate based in Rouse’s Stockholm office.

Ya Wen is a Senior Trademark Attorney based in Rouse’s Beijing office.