On March 26, 2020, just a few weeks before ESPN would capture 6.1 million viewers in a single night thanks to the debut of a Michael Jordan-centric docuseries called The Last Dance, the Chinese equivalent to the United States Supreme Court had the basketball legend on its mind. In a highly-anticipated decision, the Chinese Supreme People’s Court (the “SPC”), the highest court in China, ruled in favor of Michael Jordan, recognizing the former National Basketball Association superstar’s prior rights in the name “Qiaodan” in Chinese characters.

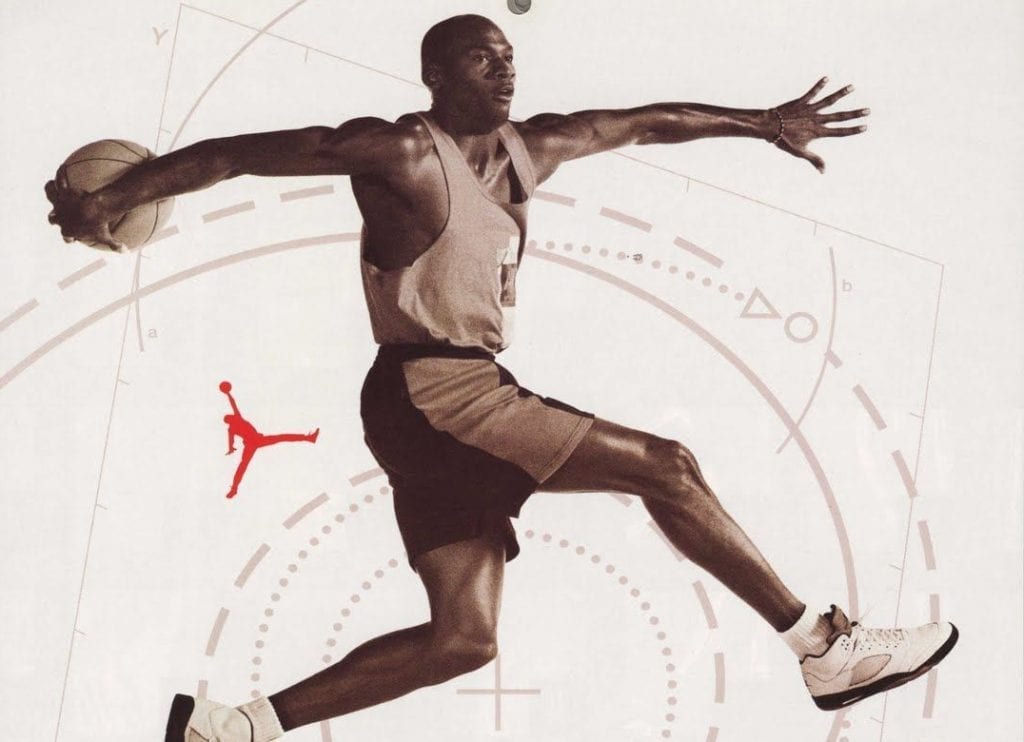

Siding with Jordan due to the established link between the sports mega-star and the “Qiaodan” mark based on the evidence presented at trial, the SPC ruled against Qiaodan Sports Co., Ltd, the Chinese sportswear company that had registered the “Qiaodan” name – a commonly recognized phonetic translation for the name “Jordan” – along with a design that depicted a basketball player in midair attempting a layup more than a decade before in connection with its manufacturing, marketing, and sale of clothing.

In April 2007, Qiaodan Sports applied for the “Qiaodan” trademark. It was granted a registration in April 2010, only to have lawyers for the former Chicago Bulls star file a request to cancel the trademark. When the trademark review body ruled in favor of Qiaodan Sports, Jordan filed suit, which has been underway ever since.

In connection with the latest proceedings, which follow from unfavorable decisions for Jordan before the Beijing Intermediate People’s Court and the Beijing Higher People’s Court, Qiaodan Sports unsuccessfully argued that there was not an exclusive link between Michael Jordan and “Qiaodan in Chinese characters” – and thus, its use was not legally out of bounds – because “Qiaodan in Chinese characters” has its own meaning — “grass and trees of the south” in Chinese.

Even if “Qiaodan in Chinese characters” can be regarded as the corresponding Chinese translation for the name “Jordan,” Qiaodan Sports claimed that “Jordan” itself is merely an ordinary surname in English, and an exclusive link to Michael Jordan had not been established based on the evidence in the trial.

Unpersuaded by Qiaodan Sports’ assertions, the SPC stated in its re-trial decision that based the use of the “Qiaodan” mark and the reputation of Michael Jordan, the evidence did, in fact, “establish a link” between “Qiaodan in Chinese characters” and Michael Jordan, which gave rise to the necessary name rights protection for Michael Jordan.

Quashing the decisions of the lower courts, the SPC remanded the case back down to the China National Intellectual Property Administration, which will review the trademark again, and almost certainly, hand down a victory for Michael Jordan and invalidate Qiaodan Sports’ registration.

The long-running case is the last in a series of high-profile trademark invalidation actions that Michael Jordan commenced in 2012 against Qiaodan Sports in connection with the whopping 78 registrations it received for trademark that the Jordan believed infringed his rights in his name, among other legal violations.

Following a handful of losses before the national trademark body and the lower courts, Jordan sought a re-trial of the 78 cases before the SPC, which agreed to take on 10 of the cases and eventually ruled in favor of Michael Jordan in four of the re-trial decisions, including the present one. That means that Jordan’s rate of legal wins (4 of the 78 cases he initiated against Qiaodan Sports) is not quite as high as his career game wins (706 wins out of 1,072 games). As for why he only prevailed in four cases, Jordan’s low success rate is largely tied to the fact that he waited too long in most cases to object to the trademarks, given that Chinese Trademark Law provides a five-year time bar on the invalidation of a trademark registration.

While the mark in the case at hand was registered in 2010, most of Qiaodan Sports’ 78 Jordan-related trademarks had been registered for more than five (5) years in 2012 when Jordan initiated the proceedings.

As for the significance of this case, in particular, going forward, it is noteworthy that the SPC shifted from the ”exclusive link” approach adopted by the Chinese courts in the past, including the Beijing High People’s Court in this the present case, to a more relaxed “established link” approach. This is likely a win for rights holders, such as Jordan, as it sends out a message that Chinese courts are becoming will be less likely to tolerate the rampant, free-riding activities of trademark squatters who register famous names as trademarks.

On April 8, 2020, Qiaodan Sports posted an announcement via its official Weibo account to its business partners that based on the company’s win in 74 of the 78 cases, including those relating to the company’s core registrations for the mark “Qiaodan in Chinese characters”, “Design” and “QIAODAN”, the present re-trial decision will not affect the company’s use of its existing trademarks and will not affect the company’s normal business operations.

From a U.S. standpoint, this case demonstrates the importance of worldwide protection of trademarks and protection of the right of publicity, where applicable. As celebrities’ – and fashion and beauty brands, alike – continue to gain increased recognition on a global scale, thanks, in large part to various technologies, including social media, it is important to consider the value and monetization of a personal brand, and to protect that brand by registering it with trademark offices in key jurisdictions where there are lots of fans and where goods and services are sold, licensed, and/or manufactured.

Fashion brands and celebrities, alike, should take heed of the Qiaodan Sports litigation saga as a case in point where acting early to protect global rights would have saved Michael Jordan from eight years of litigation and a Chinese doppelgänger brand clouding his image.

Beyond the U.S. and a few other common law countries that allow for protection of unregistered names and symbols, it can be difficult to enforce trademark rights against an unauthorized user of a mark if they were first to file a trademark. Such “first to file” countries do have laws against bad faith squatters as well as special laws protecting famous marks. However, the evidentiary standards can create hurdles, especially in cases like the Qiaodan Sports case in China, where the mark might be subject to various translations and it may be difficult to show an “established link” let alone an “exclusive link” between the infringing mark and the celebrity based on the available evidence. This case is helpful for rights holders going forward in China, though filing early and often remains the best strategy for global branding.

Lilian Shi is a partner at Dorsey & Whitney’s Hong Kong Office. Tiffany Shimada is a partner at Dorsey & Whitney’s Salt Lake City office. (Edits/additions courtesy of TFL)