In a couple of the most interesting examples of color-specific trademarks as of late, Glossier filed two applications this spring, seeking registrations that extend to its use of a specific millennial pink hue on the interior of its multi-sized packaging boxes and on pink bubble wrap pouches, as well, on the basis that when consumers see those things in that color, they link them to a single source … the burgeoning 5-year old Glossier brand.

In its preliminary review of the beauty unicorn’s applications this summer, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) refused to register either mark. While trademark protections can cover any word, name, symbol, or design (including logos, colors, sounds, product configurations, etc.), or any combination thereof, the national trademark body has some issues with Glossier’s marks, which it set out in Office Actions last year. For instance, a USPTO examining attorney initially determined that the pink bubble wrap trademark is problematic, as it “appears to be a functional design … with a specific utilitarian advantage,” namely, the bubble wrap serves “a protective feature for the goods being stored in the interior,” thereby making it ineligible for registration. Glossier’s counsel has since pushed back against this.

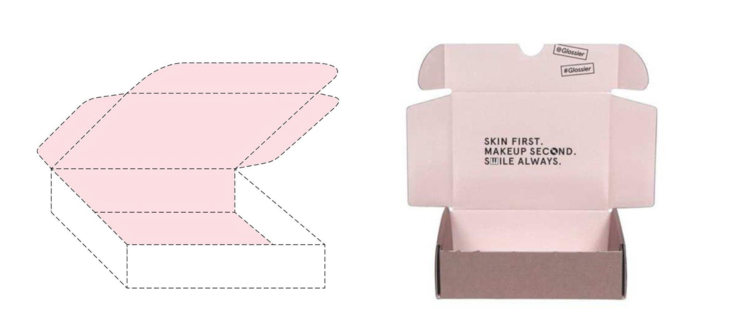

Meanwhile, a USPTO examiner also took issue with Glossier’s application for boxes of “various sizes” that have a pink-colored interior, asserting in a separate letter in August that the mark is not registrable because, among other things, it is decorative and thus, does not function as a trademark. According to the USPTO, consumers are not likely “to perceive the color pink as identifying the origin of [Glossier’s] goods; but rather, they will perceive the colors as decorative features … because they are accustomed to encountering various colors, including pink, on various packaging for cosmetics and beauty care goods.”

On the heels of filing a response to the bubble wrap pouch Office Action early this year, Glossier has responded to the pink-lined box Office Action. In doing so, it opted to refine the language of the trademark description to limit its scope from pink-lined boxes generally to the “color pink [as applied to the inner surface of portions of boxes] so that it contrasts with the rest of the box.” As such, Glosser’s clarification mirrors the language that Christian Louboutin was forced to adopt in connection with the modification of its trademark registration in light of the outcome of the case that it filed against Yves Saint Laurent in April 2011. (Louboutin’s trademark registration now only extends to a lacquered red sole on contrasting-colored footwear; as opposed to broadly covering a “lacquered red sole on footwear”).

Glossier’s pink box trademark drawing (left) & specimen (right)

In response to the USPTO examiner’s previous assertion that the use of the color pink on the boxes is functional and therefore, ineligible for registration, Glossier claims that not only are there “numerous other color options available for other parties to use on the interior of boxes for cosmetic products,” it states that “there is no particular value or advantage to making a pink interior that contrasts with the rest of the box.”

With the issue of functionality out of the way, counsel for the buzzy brand, which was born from then-blogger Emily Weiss’ beauty website Into the Gloss in 2014, asserts that it has met the second prong at play – secondary meaning – given “the extensive evidence … that relevant consumers immediately recognize [its unique and distinctive use of] the color pink as applied to only the interior of a box indicates that the cosmetics and skincare products originate from Glossier and not from any other source.” Per Glossier, “This is bolstered by the fact that so many of [its] purchasers make a point to share photos of not just the cosmetic products, but also the box they come in, [which] speaks to the distinctiveness of the Glossier packaging.”

“These social media posts not only demonstrate that many consumers already associate the pink box with [Glossier], but they also serve to educate even more consumers and reinforce the association between the pink box and Glossier,” the company’s counsel states.

Such usage of color is not unheard of. Pointing to a famous example in which the use of a color maintains source-identification capabilities, and thus, trademark rights, Glossier’s counsel states that “it is well known that Christian Louboutin owns trademark rights … for ‘a red lacquered outsole on footwear that contrasts with the color of the adjoining (‘upper’) portion of the shoe,’” noting that “a federal court held that this trade dress was enforceable and protectable insofar as it would not preclude competitors’ use of red outsoles in all situations, such as monochromatic use.”

“Similarly here,” Glossier’s counsel asserts that the brand “seeks protection for a narrowly defined display of the color pink that is capable of acquiring distinctiveness just as Louboutin’s red sole was.” And more than that, the brand’s counsel says that Glossier’s particular “use of the color pink is analogous to Tiffany’s use of robin’s egg blue, in which Tiffany has secured multiple trademark registrations as applied to its product packaging.”

One of the most striking differences between Louboutin and Tiffany & Co., and Glossier – from a secondary meaning perspective – is, of course, the length of time that they have been using their respective color marks and the related saturation of the market with those marks. Unlike, Tiffany and Co., for instance, which has been using its robin’s egg blue since 1889, Glossier has been using its signature pink for just over five years. When it comes to Louboutin, the level of fame associated with its use of the red sole is noteworthy in that it has appeared on nearly every major red carpet across the globe, and generated demand that sees the brand sell more than 1 million pairs of its pricey, red-soled footwear per year.

More than that, the Tiffany & Co. and Louboutin likely boast significantly more sizable marketing budgets (although marketing spending by direct-to-consumer brands is on the rise), which enable them to boost brand awareness and thus, establish and maintain a link between their use of color and the source of their products in the minds of consumers

However, even if time and reach are not on Glossier’s side compared to the aforementioned companies, not all is lost. Chances are, social media (and traditional media attention, as well) has helped the 5-year old direct-to-consumer company to boost its level of sales (which were expected to surpass $100 million in 2018), brand awareness, and critically, consumer awareness of its trademark in the market beyond that of a traditional brand, something that very well might help the company make its case for secondary meaning.

All the while, Glossier and its savvy legal counsel are laying the groundwork in an interesting and informative demonstration of how a young brand can claim rights – and potentially amass registrations – in less-conventional branding elements (something Off-White has also been exploring via quotation marks and red zip ties), a move that has traditionally been used almost exclusively by more established (read: older) companies, making this a matter worth watching.