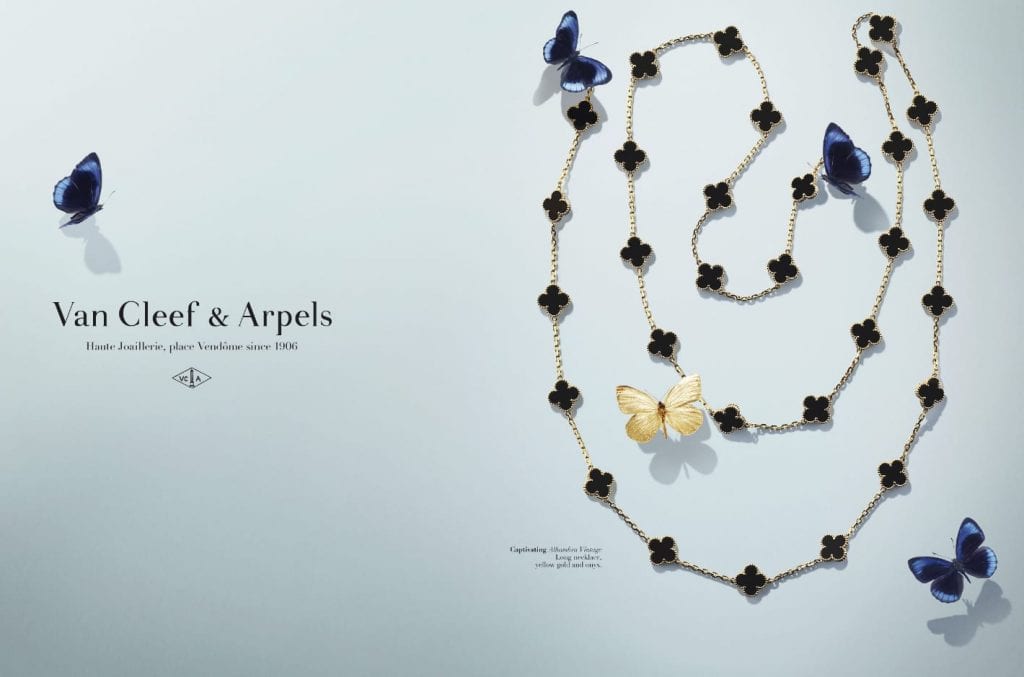

Created in 1968 as a luxurious take on the four-leaf clover, a timeless symbol of luck, Van Cleef & Arpels’ Alhambra jewelry collection is among its most well-known offerings. “The first Alhambra design was an opera-length necklace punctuated with 20 clover-shaped motifs crafted with the design’s signature beaded edges,” according to Sothebys. “As the 1960s made way for the 1970s, the design became hugely popular among celebrity clients, who layered many Alhambra necklaces of different sizes and with different gemstone combinations for the quintessential daytime look.”

American actress-turned-Princess of Monaco, Grace Kelly was among some of the “long-time devotees of Van Cleef & Arpels and collectors of Alhambra necklaces,” further helping to put the design on the map, one that has endured in popularity for more than five decades. In furtherance of such longstanding appeal and in light of the fact that the Alhambra line has (arguably) come to indicate a single source, Netherlands-based Van Cleef has sought legal protections for it across the globe, with one ongoing trademark quest – a back-and-forth in China – proving to be particularly interesting.

On November 19, 2014, Van Cleef filed an application with the Chinese Trademark Office for a three-dimensional trademark (no.15736970) for its specific clover motif for use in class 14 on goods, including “watches; rings; bracelets; earrings; necklaces; jewelry; [and] watch cases.” Less than two years later, in January 2016, the Chinese Trademark Office gave the application the go-ahead, and issued a registration to Van Cleef for the little clover symbol.

Ultimately, the registration would not prove to be without issues, as in April 2018, a Chinese citizen named Qingyu Bi initiated proceedings with the China National Intellectual Property Administration (“CNIPA”) seeking to have the trademark registration invalidated. According to Bi’s filing, Van Cleef’s clover lacks the necessary distinctiveness to be registered, and in July 2020, the CNIPA agreed, determining that because the consuming public is unlikely to easily identify the source of the motif, it is not capable to distinguishing the products of different companies. In other words, the little clover fails to function as a trademark.

Handed a loss by the national trademark body, Van Cleef took its case to the Beijing Intellectual Property Court on the basis that the clover mark is an original design created by – and associated with – Van Cleef in part because it is different from other jewelry items in the market, and that Van Cleef has been actively using and promoting the clover mark over a long period of time, thereby, giving rise to trademark rights.

Much like the CNIPA, the Beijing Intellectual Property Court sided with the CNIPA. According to the court, the clover symbol – even if it is an original creation of Van Cleef – is easily identified as the shape of (or part of the shape of) the jewelry product as a whole in the minds of consumers, thereby, making it difficult for the clover to readily identify and distinguish the source of product.

The court was similarly unpersuaded by the evidence that Van Cleef produced to demonstrate its widespread marketing and advertising of the specific Alhambra clover in the Chinese market, and held that even if the brand has heavily promoted the clover mark, it “cannot prove [its] use of the [clover] pattern is trademark use,” thereby, weighing against Van Cleef’s assertion that the symbol has acquired distinctiveness in the market.

In response to yet another loss, Van Cleef has further appealed to the Beijing High People’s Court, where the case is currently underway.

The matter is striking, according to HFG Law & Intellectual Property attorneys Ariel Huang and Chunyan Zhang, who claim that Van Cleef’s “four-leaf clover” jewelry is, in fact, “quite famous in China,” but despite such fame, the symbol has, nonetheless, been rejected as a 3D trademark to date.

As for how brands can effectively create 3D marks that meet the requisite threshold of distinctiveness for protection in China, Huang and Zhang say that “the answer lies in two aspects: 1) making sure that the trademark itself is distinctive in nature; and 2) if it is not inherently distinctive” – which is commonly the case when a mark is a 3D one – “collecting sufficient evidence to prove its acquired distinctiveness.”

“Lacking inherent distinctiveness does not mean absolute impossibility in obtaining a registration for a 3D trademark,” they note. For marks that are not inherently distinctive, such as those that are three dimensional, a brand’s ability to succeed in registering and maintaining a registration will depend on its ability to produce evidence showing that “the relative public [view] the pattern as a sign indicating the source of the products” at issue.

Evidence that is “normally useful” in such situations includes “overseas or domestic registrations as proof of distinctiveness; use of the trademark in the prior three years in commerce in China; actual evidence of distinctiveness, such as market survey reports,” according to Dechert LLP’s Jingzhou Tao and Yingying Zhu.

Unfortunately for Van Cleef and other brands seeking rights in 3D marks, the situation becomes more complicated when the shape at play forms part of the relevant product, such as the charm on a necklace. Citing Article 9 of the Chinese trademark act, Huang and Zhang state that “if the relative public [views] the pattern merely as (part of) the shape of the product as a whole rather than as a trademark, the pattern will not serve to distinguish the product [upon which it appears from those of others] and thus, will not be deemed as a trademark” without a showing of secondary meaning.

As such, the trademark applicant will need to produce “sufficient evidence to prove it has acquired distinctiveness through use.”

Depending on whether the evidence submitted by Van Cleef will enable the clover to be considered “trademark use,” the jewelry company may follow in the footsteps of Ferrero Rocher, which was ultimately able to convince the Chinese trademark office to register the colors and the packaging of its famous chocolates as a 3D trademark, but only after a protracted legal battle. And even if the brand is not successful on the trademark front (and it very well might not be given the “much stricter and more abstract [requirements at play for 3D marks] than the criteria applied for word marks or logos”), Huang and Zhang state that Van Cleef is not entirely unprotected, as it “has different design patents granted in China, including the Alhambra series.” As such, even if the trademark case is not a success, “it will cause a big storm for the brand within the life of those design patents.”