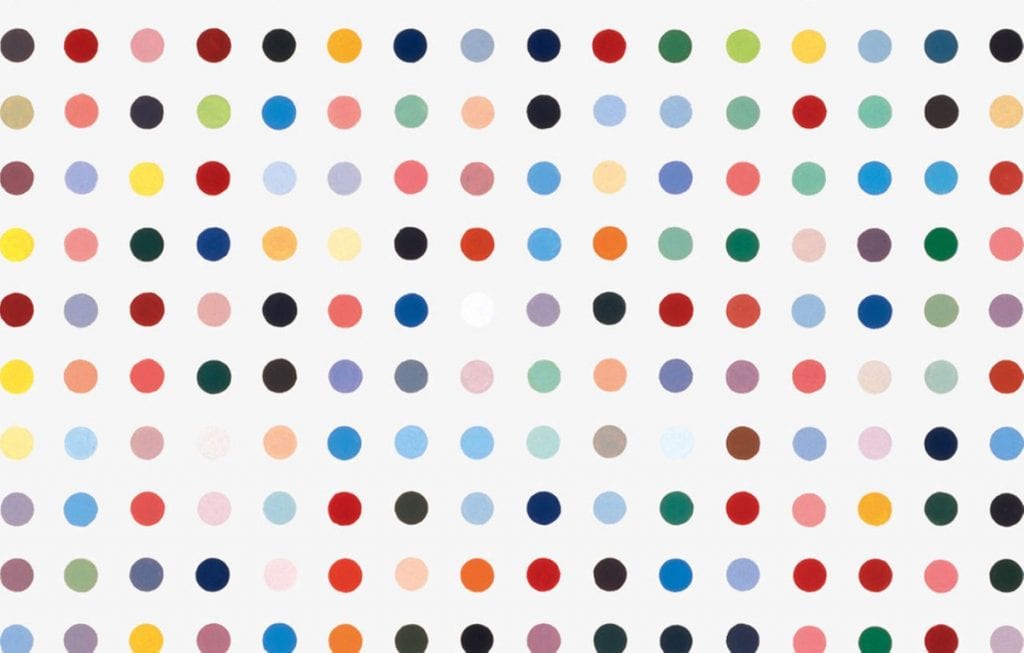

Among some of the “most widely recognized works” of Damien Hirst come from a series a spot-centric paintings. A printed version of one of those colorful and dizzyingly grid-like works – which first appeared in the mid-1980s and have been produced almost every year since (as of 2012, Hirst said that he had been producing an average of 60 spot paintings a year) and which largely come with names “titles that are taken arbitrarily from the chemical company Sigma-Aldrich’s catalogue ‘Biochemicals for Research and Diagnostic Reagents,’ a book Hirst stumbled across in the early 1990’s” – is now the center of another largely controversial work.

As it turns out, while 54-year old, British-born Hirst was busy creating a rainbow design to “pay tribute to the wonderful work [the United Kingdom’s National Health Service] staff are doing in hospitals around the country,” a group of American artists were crafting something of their own. Brooklyn-based creative collective MSCHF, which managed to purchase a limited print of Hirst’s $30,000 spot painting L-Isoleucine T-Butyl Ester, which Hirst created in 2018, decided to “indulge in a bit of creative destruction.” (The actual spot painting themselves usually sell for upwards of $1 million).

In other words, the group cut out each of the Damien Hirst-constructed spots – 88 in total – and sold them individually for $480 apiece, making a statement in the process, one that protests the treatment of artworks as “the archetypal value sink” with investors pooling together to buy art, which they then store and ultimately “flip [to another buyer or group of buyers] like a giant bill in a colorful currency arbitrage.”

“Could there be a more tailor made [sic] vehicle for the affluent to store their wealth?,” MSCHF asks.

(Veteran art dealer Michael Findlay touched on this (albeit from a slightly different angle) in his book, The Value Of Art: Money, Power, Beauty, in which he said that many artworks, particularly Hirst’s largely-mechanically-created spin paintings “come, like Starbucks coffee, in three sizes,” making them “more or less interchangeable and sold as branded items . . . rather than as unique works of art,” and thus, turning them into “commodities in the artist’s brand, or his signature, has replaced the artist’s hand as the foremost signifier of a work’s value and meaning” and “the strength of the artist’s name alone determines the value of the work”).

MSCHF – which is heavily funded (it has raised “more than $11.5 million in outside investments since the fall of 2019”) and known for its “news-making stunts that straddle the lines of conceptual art, contemporary design, and internet gaggery,” according to Artnet – sold off the 88 individual 3.5-inch-wide spots within a matter of hours, while the ravaged canvas, itself, complete with 88 holes, is being auctioned off. The current bid on MSCHF’s site is $144,250.

Reflecting on the art statement-turned-sale, the Telegraph states that MSCHF “decided to deface the work to illustrate their distaste for the commodification of art,” and in doing so, the group has made headlines across the world. Despite the widespread media attention, element of MSCHF’s venture has gone undiscussed: VARA.

A relatively obscure federal law, the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 (“VARA”) provides certain artists – such as those behind single or limited edition paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, or sculptures – with the right to sue of their “moral rights” in a work are violated.

In other words, the law enables artists to prevent the destruction of a work of art if it is of “recognized stature” and allows artists to control the use of their name in connection with alterations of their works (and the sale of altered works), among other things, even after they have sold their creations. While copyright and physical ownership are property rights that can be freely transferred, moral rights stay with the artist no matter what.

Unlike trademark-bearing products and most copyright-protected works, which, once they are sold by the rights holder’s, his/her rights to sue on infringement grounds are extinguished, VARA provides artists with an interesting remedy.

Hardly a sweeping catch-all that protects all artworks and their creators, VARA “applies only to a restricted category of visual artworks, extends only limited rights, and is subject to loopholes, exclusions, and waiver provisions that substantially erode its powers,” according to former National Endowment for the Art general counsel Cynthia Esworthy. One instance that fits neatly within the bounds of VARA, per Esworthy? “You are a well-known painter. You discover that a company that has purchased one of your canvasses is advertising one-inch square portions of it so that buyers can ‘own an original painting’ by you.”

Sounds a bit familiar, doesn’t it.

No mention has been made (to date, at least) that Hirst – who is famous “for pushing the boundaries of art, himself,” as Art Critique puts it – has any intention to take on MSCHF over its sale of the “single spots cut from Damien Hirst Spot Painting ‘L-Isoleucine T-Butyl Ester,’” as they describe the individual pieces of art on VARA grounds. However, if he were, he would have to establish that his print is of “recognized stature” and that MSCHF’s cut-and-sale of the work is “prejudicial to his honor or reputation.”

If he could prove that, he would be looking at damages under VARA that consists of actual damages or statutory damages ranging from $300 to $30,000 per work that can be increased up to $150,000 per work for willful violations. Although, it likely would not be about the money for Hirst, who has routinely been labeled as the most commercially successful artist in the world.

As for whether MSCHF’s potentially transformative – and thus, fair – use of Hirst’s original work is relevant in a VARA setting, it might be. Cathay Smith asserted in her 2019 paper, “Creative Destruction: Copyright’s Fair Use Doctrine and the Moral Right of Integrity,” that while VARA “includes language explicitly making the right of integrity” – which applies when “separated panels of a single work of art are sold,” for instance – “’[s]ubject to’ copyright’s fair use doctrine, there have been no decisions in the U.S. interpreting how the doctrine might apply to a moral right of integrity claim.”