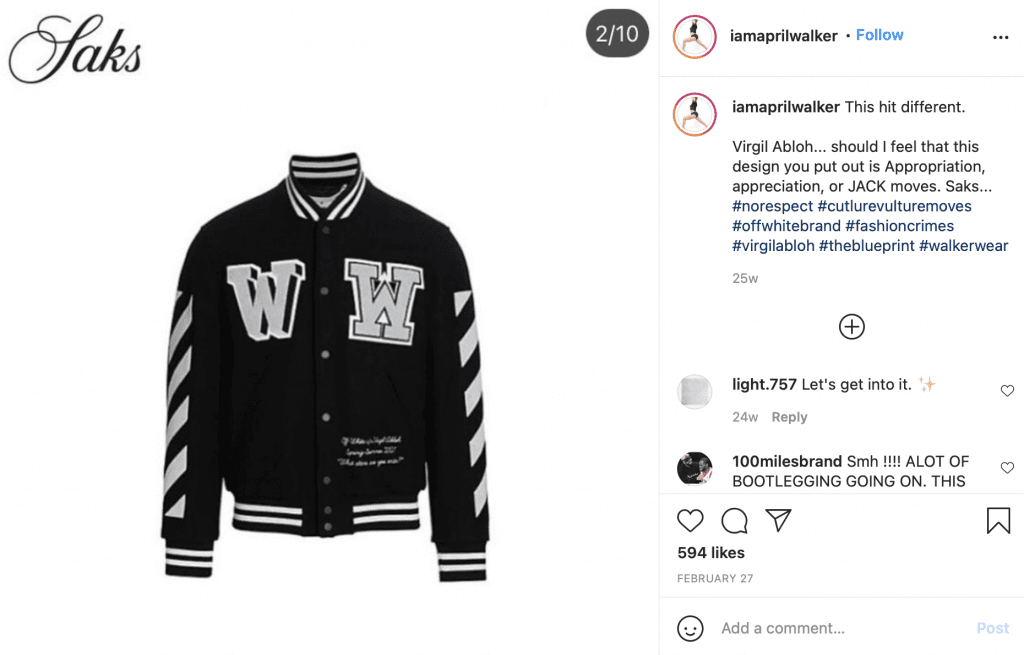

Walker Wear is taking on the soon-to-be LVMH-owned Off-White in a new lawsuit. In the recently-filed trademark infringement and dilution complaint, Walker Wear asserts that in line with Off-White founder Virgil Abloh’s “cheat code,” which sees him “chang[e] others’ designs by only ‘three percent’ and then claim the design as his own,” Off-White is making and selling a $2,234 jacket bearing “a design nearly identical to Walker Wear’s storied WW XXL Athletic mark design.” And despite alerting Off-White that the jacket is causing actual confusion among consumers, who have “mistaken Off-White’s jacket for [Walker Wear founder April Walker’s] work,” Walker Wear claims that Off-White continues to offer up the allegedly infringing garment.

According to the complaint that it filed against Off-White, as well as its stockists Farfetch and Saks Fifth Avenue, in a New York federal court on August 20, Walker Wear alleges that it has been using the WW XXL Athletic mark and related designs since at least 1993 under the watch of “streetwear pioneer” April Walker, whose designs have been sold for “nearly thirty years, have been worn by many of the most famous hip-hop entertainers, and have been the subject of extensive media coverage.” Over the course of nearly three decades, the New York-based streetwear brand claims that it has “invested substantial time, effort, and resources in developing the [WW XXL Athletic] trademark and trade dress rights,” and as a result, its marks have “become widely associated with Walker Wear and acquired substantial recognition, goodwill, and fame.”

Specifically, Walker Wear contends that its mark “consists of two stylized W’s, centered and slightly overlapping,” and which “typically appear in silver, set off against a dark blue or black background.” The brand claims that “this shape and color stylization is unique in the fashion industry, and renders the mark and trade dress inherently distinctive.” (Walker Wear filed a trademark application for registration for a mark consisting of “stylized letters WW and the stylized letters XXL and the wording ATHLETIC WALKER WEAR in upper case letters” with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in March for use on jackets, athletic shirts, sweatshirts, and t-shirts.)

In light of the fact that “the fashion is cyclical” and that styles from the 1990s – which is when Walker Wear says that it “was especially influential” – is “very much back in style,” the brand argues that Abloh “appears to be applying his ‘cheat code’ to [its] intellectual property.” At the same time, Walker Wear points out that “larger fashion houses” generally have a pattern of “misappropriating the work of independent designers like [Ms. Walker] on the assumption that she and others like her will be unable to meaningfully challenge them in legal proceedings,” and even more specifically, “Off-White and its founder, Virgil Abloh, have an unfortunate history of deriving from the creativity of other designers.”

Against that background, Walker Wear alleges that it “recently became aware” that Off-White was making and selling – including at Saks and farfetch.com – a jacket that infringes “the distinctive Walker Wear ‘WW’ design … without the permission of April Walker or Walker Wear.” The brand claims that this is “a clear and substantial violation of [its] intellectual property rights,” and has led to confusion among consumers, who have been unsure about the source of the jacket and/or Walker Wear’s connection to Off-White’s “copycat” product.

Hardly a coincidence, Walker Wear asserts that “given Ms. Walker’s iconic status in the streetwear fashion industry and Mr. Abloh’s knowledge of the industry, Off-White was almost certainly aware of the mark prior to designing, producing, and selling the infringing jacket.” Moreover, the plaintiff argues that “the similarity of the marks – particularly given that ‘WW’ appears to have no particular significance for a brand called ‘Off-White’ – further suggests the defendants’ bad faith in using the mark.”

With the foregoing in mind, and given the parties’ alleged inability to resolve the matter out of court, Walker Wear sets out claims of trademark Infringement and dilution, unfair competition, and unjust enrichment, and contends that Off-White has also violated N.Y. Gen. Bus. Law § 349, which prohibits deceptive and misleading business practices, and is seeking monetary damages and injunctive relief.

Immediately after filing its complaint on Friday, Walker Wear followed it with a motion for a preliminary injunction, In furtherance of its quest for a preliminary injunction in order to prevent the defendants – including Saks and Farfetch – from making unauthorized use of the Walker Wear mark for the duration of the litigation, Walker Wear elaborates on the allegations in its complaint, alleging that its counsel sent a cease-and-desist letter to the defendants in June, and that “notwithstanding that notice, and not withstanding their knowledge of evidence of actual confusion, on July 6, 2021, Off-White and Saks flatly refused to cease their infringing activities.”

On the infringement front, Walker Wear argues that an injunction is appropriate, as it is likely to succeed on the merits of its case in light of its valid and protectable rights in the “WW” mark, which it claims has “achieved secondary meaning” as a result of decades of use and widespread media attention, and the potential for confusion, which it claims is likely given the similarity of the two companies’ uses of the “WW” mark, and the proximity of the two companies and their offerings in the market, among other things.

Walker Wear also asserts that it is likely to succeed on its dilution claim, as its “WW” mark is famous, and that Off-White’s “unauthorized use ‘whittl[es] away’ at [that famous] mark and thus, tarnishes and blurs its distinctive quality.”

Social Media Comments as Confusion

A few things jump out (to me) as striking in the case, not least of which are the differences between the two parties’ uses of the letters – from the spacing to the stylization. It is worth noting, in particular, that Walker Wear specifically cites the presence of “slightly overlapping” W’s in its description of its mark in the complaint, which is not present in Off-White’s presentation of the letters. So, while Abloh very well may have gotten (i.e., almost certainly got) the idea to put two “Ws” on the jacket from Walker Wear, the end result is ultimately pretty different save for the use of the same letters, of course. This is significant because Walker Wear’s trademark rights will almost exclusively extend to its stylization of the letters, not to the actual letters, themselves, in much the same way as the Washington Nationals, for instance, do not have sweeping rights over the letter “W” but do have strong rights in their specific stylized depiction of the letter. The same can be said of Weight Watchers and its stylized two-W logo.

Beyond that, the emphasis that Walker Wear places on the existence of actual confusion among consumers when it comes to Off-White’s allegedly infringing use of the “WW” mark is interesting. While evidence of actual confusion is not necessary to show that there is a likelihood of confusion, it can, nonetheless, be an indication that future confusion is likely. That is, of course, if the evidence of actual confusion is persuasive, which might not be the case here if for no other reason than the examples of actual confusion cited by Walker Wear consist of comments made in response to an Instagram post by Ms. Walker calling out Off-White for the allegedly infringing jacket.

Generally speaking, “Persuasive actual confusion evidence based on internet comments or search results is uncommon,” according to Fenwick partner Eric Ball, who has noted that “even when admissible, internet evidence may not support relevant consumer confusion, or there may be insufficient evidence to show a customer is likely to be confused.” And “even where internet evidence can help,” he notes that “it likely will not be strong evidence of a likelihood of confusion.”

This reminds me of Nike’s response to the inclusion of social media comments as evidence of actual confusion in the trademark infringement case filed against it over the logo that appears on shoes for skateboarder Shane O’Neill. (This is merely one example of a growing number of instances in which brands, including Nike, have relied on comments from social media users as examples of actual confusion.) In filing suit against Nike, digital music startup Soulection asserted that consumers were actually being confused by Nike’s use of a lookalike logo, and included social media comments as evidence of that. Nike argued that while consumers may be making comments about the similarity of the logos on social media, it “is not aware of any confusion in the purchasing context whereby consumers believe that there exists an affiliation between NIKE and Soulection as a result of NIKE’s use of the Sun Shane graphic.” That same sentiment might be relevant here.

Counsel for Off-White told TFL that it cannot comment on pending litigation, but based on correspondences between the two companies’ counsels, Off-White has preliminarily pushed back against the plaintiff’s allegations on the basis that Walker Wear’s use of the “WW” mark “appears to be more historical in nature,” seemingly suggesting that its has not consistently used the mark, and that the market is already rife with other uses of the “WW” mark, and that such a lack of exclusive use lessens the source-identifying power of Walker Wear’s mark, among other arguments.

Chances are, Off-White will also likely argue that it is not using the two “Ws” in an effort to alert consumers about the source of the jacket, and instead, is using the letters in a decorative capacity, and thus, should not be on the hook for infringement. And beyond that, it will probably claim that any potential for consumer confusion here is resolved by the fact that the jackets clearly include well-known Off-White trademarks on them – both in terms of the “Off-White c/o Virgil Abloh” word mark and the brand’s trademark-protected diagonal stripe motif – which serve to indicate the source of the product to consumers. That claim may not rule out the potential for confusion as to whether the jacket is the result of a collaboration between Off-White and Walker Wear. However, the different styles and placement of the “Ws” on Off-White jacket versus Walker Wear’s t-shirts and sweatshirts could potentially do away with that issue.

The case is Walker Wear LLC v. Off-White LLC, et. al., 1:21-cv-07073 (SDNY).