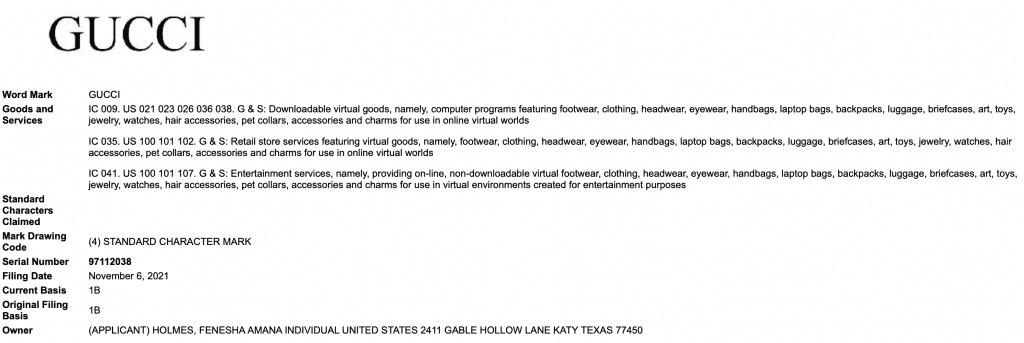

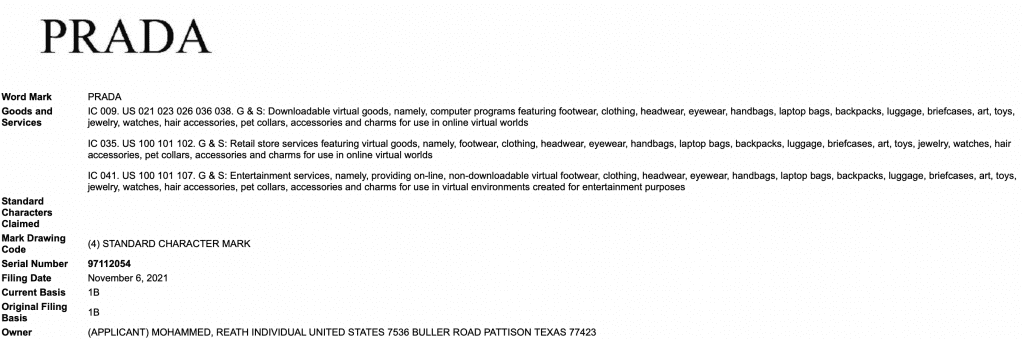

Metaverse-focused trademark applications for registration for Gucci and Prada that were filed by unaffiliated individuals – for use on “downloadable virtual goods, namely, computer programs featuring footwear, clothing,” etc., “retail store services featuring [such] virtual goods,” and “entertainment services, namely, providing on-line, non-downloadable virtual footwear, clothing,” etc. – amid a boom in interest in NFTs and the metaverse are unsurprisingly garnering pushback from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. In respective Office actions issued this week, examining attorneys for the trademark office preliminarily refused to register the Gucci and Prada word marks on a number of bases. The most obvious: A likelihood of confusion between the applied-for marks and the valid trademarks held by Gucci and Prada.

The Office actions that the USPTO sent to Fenesha Holmes and Reath Mohammed, the individuals who filed applications for the Prada and Gucci marks in November 2021, are not unexpected. As TFL exclusively reported last year, the applications “are unlikely to pose real problems for [Gucci and Prada] in the U.S., given that trademark rights are awarded based on actual use of a mark. It is also worth noting that brands like Gucci, for example – which has partnered with Roblox and put its famous logos on a virtual experience and corresponding goods – are actively amassing trademark rights in lieu of metaverse-specific trademark registrations of their own by virtue by using their marks in these classes of goods/services. And these rights would trump any claimed by the unaffiliated third parties.”

Nonetheless, there are a few interesting aspects of the Office actions in response to the squatter-like applications, namely, the examiners’ discussions about the similarity of the marks in the applications filed by Holmes and Mohammed to those held by Gucci and Prada – in particular, the relatedness of the goods/services at issue.

“Real” World vs. Virtual World Goods and Services

Laying out some relevant points on the likelihood of confusion front (and then looking to the DuPont factors in order to gauge the potential for consumer confusion), the USPTO examiners assert that Trademark Act Section 2(d) “bars registration of an applied-for mark that is so similar to a registered mark that it is likely consumers would be confused, mistaken, or deceived as to the commercial source of the goods and/or services of the parties.”

The examining attorneys’ discussions about the goods and services are compelling, as while Gucci and Prada have consistently used – and maintain a long list of trademark registrations for – their names, none of those registrations specify virtual goods, retail services for virtual goods and/or entertainment services focused on virtual goods as among the goods/services. (No, this does not really matter given that both Gucci and Prada are actively using their marks on NFTs and/or in the metaverse, and thus, have earned rights via such use, but hold on.)

In light of the two Italian brands’ lack of metaverse/NFT-specific trademark registrations for their word marks, the USPTO examiners look at the classes of goods/services that are listed in their existing registrations. For Gucci, the examiner states that two of its registrations for the Gucci name in Class 35 “use broad wording to describe retail store services featuring clothing, jewelry and handbags.” This language “presumably encompasses all services of the type described, including the narrow[er] retail store services featuring virtual goods in these categories” listed in Holmes’ application, the examiner asserts, noting that “the services of the parties have no restrictions as to nature, type, channels of trade, or classes of purchasers,” and thus, are “presumed to travel in the same channels of trade to the same class of purchasers.”

Against this background, the examiner finds that the services listed in Holmes’ application and the ones listed in Gucci’s registrations “are legally identical.” This is conclusion is significant, as it would seemingly apply even if Gucci was not actually operating in the virtual world and only had its traditional “retail store services” registrations to rely on. Put another way (and as we already suspected), companies’ trademark rights in/registrations for “real world” goods/services apply to the metaverse. (Note: To date, we have only really seen examples likes this arise in connection with big, very-well-known brands, and it may be safe to assume that less established companies will experience more difficulty navigating this before the USPTO and/or courts.)

The examiner doubles-down on this point, stating that the very nature of the goods at issue – both “virtual goods, such as footwear, clothing, headwear, eye-wear, handbags, jewelry, and watches,” and Gucci’s physical “footwear, clothing, headwear, eye-wear, handbags, jewelry, and watches” – are the kind that “may emanate from a single source, under a single mark,” which weighs in favor of a relatedness of the applicant’s hypothetical virtual Gucci-branded goods and those that are offered up by the Alessandro Michele-helmed fashion company. (I say “hypothetical” because neither of the applicants are making or claiming actual use of the trademark in the metaverse/on virtual goods in their intent-to-use applications.)

And still yet, the relatedness of the goods (and the likelihood of confusion) is bolstered further, according to the examiner, given that “luxury brands, including [Gucci], are selling virtual versions of their physical goods in virtual worlds.”

“Here, because the marks are identical or virtually identical and the goods and services are closely related, consumers encountering applicant’s goods and services would reasonably presume that these are produced or manufactured by the same source as [Gucci’s] goods and services,” the examining attorney states. As a result, “because consumers would be likely to assume the existence of a connection between the parties, the marks are confusingly similar,” and registration is refused.

In a separate Office action, an examining attorney refused Mohammed’s Prada mark on similar grounds, stating primarily that Prada maintains an array of registrations for “PRADA-formative marks for a variety of real goods that are consistent with [Mohammed’s hypothetical] virtual goods.” At the same time, the USPTO examiner finds that the goods/services listed in Mohammed’s application “are related to [Prada’s] registered goods and/or services” – including physical apparel and accessories, and corresponding retail services – because they are “just virtual versions of the registered goods.”

Moreover, the examiner contends that “the same providers of real fashion goods often provide virtual fashion goods, including the registrant,” and thus, Mohammed’s “goods and/or services are highly related to the registered goods and/or services.”

In addition to rejecting the applications on likelihood of confusion grounds, the examiners point to a number of other refusal bases, including Trademark Act Section 2(a), which prohibits registration of marks that may “falsely suggest” a connection with an institution. Although Holmes and Mohammed are “not connected with the goods and/or services” provided by Gucci and Prada, the fashion brands are “so well-known that consumers would presume a connection” when one does not exist. The examiners also cite prior pending applications for both “Gucci’ and “Prada” that were filed by counsel for the brands. (Interestingly, none of the brands’ prior-filed applications include any mention of virtual goods/services.)

As for the Gucci application (but interestingly, not the Prada one), the examiner stated that there is also a potential conflict given that Gucci is “primarily merely a surname.”

While applicants on the receiving end of Office actions have the opportunity to respond in order to explicitly address each refusal and/or requirement and give their applications the opportunity to potentially advance in the registration process, this round is almost certainly the last time we will hear about these applications. In all likelihood, the applications will not provide responses to the Office actions, causing the applications to be deemed abandoned, as it is essentially impossible to imagine arguments and/or evidence that they could provide to overcome the USPTO’s various grounds for refusal.

THE BOTTOM LINE: USPTO examiners are parlaying well-known brands’ “real” world trademark rights into the metaverse and finding that they are applicable to virtual goods and services – absent registrations for or potentially, even use in the virtual world. This, along with some early opinions from courts, suggests that the metaverse is not so much of a “wild west” when it comes to trademarks as the media has made it out to be, and the law likely is not in need of any major overhauls on this front in order to operate effectively.

UPDATED (Mar. 14, 2023): The USPTO has issued notices of abandonment for both applications because it did not receive a response to the Office actions from the filing parties within the six-month response period.