Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman needed a logo. In the late 1960s, their fledgling athletic footwear company called Blue Ribbon Sports was barely five years old and headed for a sweeping corporate shift, the one that would see the company branch out from footwear importer to footwear designer and manufacturer. That momentous shift was marked with a formal name change – from Blue Ribbon to Nike, a nod to the Greek goddess of victory – and the path was paved towards what would become the most valuable athletic apparel and footwear brand in the world. But long before Nike – which got its start under the watch of Knight, a former college runner, and Bowerman, Knight’s coach during his time at the University of Oregon – would actually nab its top-of-the-game title, it would need a mark to identify its brand and its offerings in the minds of consumers.

As the story goes, beginning in the late 1960s, following a stint in the U.S. Army and after earning his MBA from Stanford University, Knight took up teaching accounting at Portland State University. At the same time, he was also pursuing a more passion-oriented project: a budding footwear brand called Blue Ribbon Sports, a venture that started as a resale business of sorts, with Knight importing footwear from Onitsuka Tiger, the Japanese footwear company, and distributing it in the U.S. (That aspect of the venture would ultimately fall apart in light of tension with Onitsuka, and a fledging Nike would come into full view).

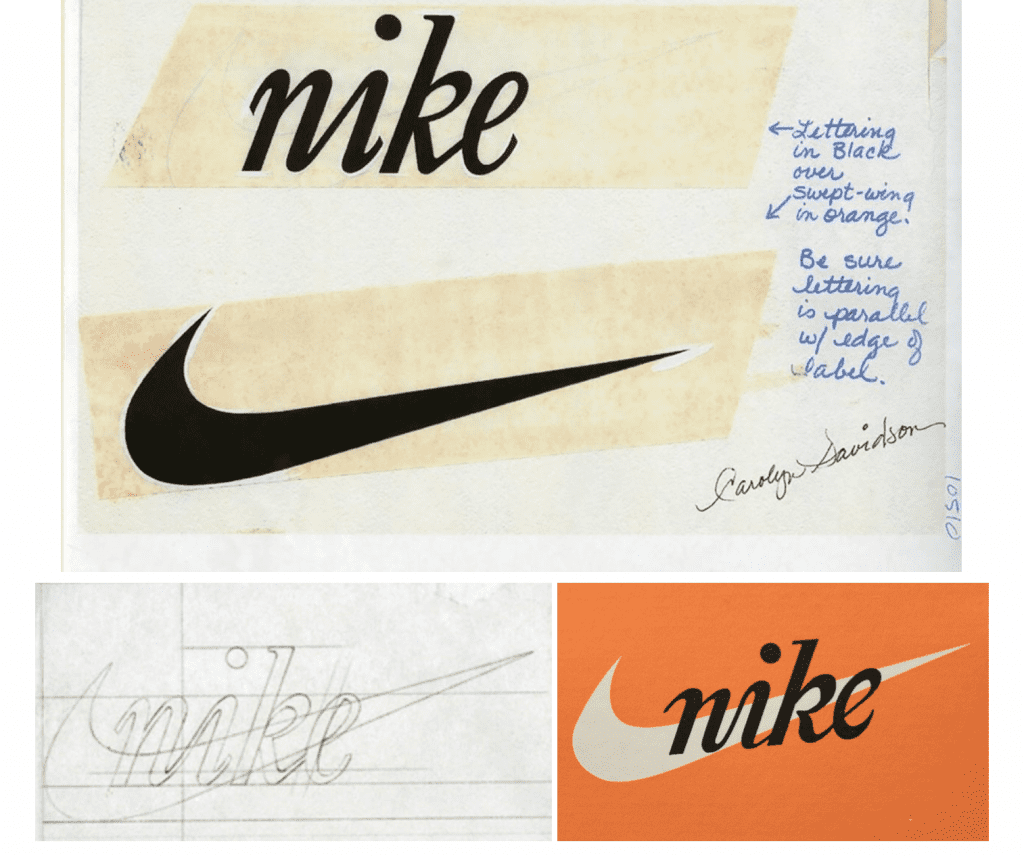

In need of charts to present to Onitsuka’s executives, Knight enlisted the help of Carolyn Davidson, a graphic design student at the university – who was in need of cash – to help him. Over time, an enthusiastic Davidson’s duties expanded from creating charts of Knight’s market findings and financial projections to designing advertisements for his up-and-coming Blue Ribbon Sports label (which would come to be entirely distinct from Onitsuka Tiger … and come to be Nike). Eventually, amidst a fall out with Onitsuka, Knight and Bowerman, preparing to launch a new shoe, needed a logo to help set their offerings apart from Onitsuka and also the likes of Puma and adidas. They enlisted Davidson to help.

Tasked with coming up with a logo, Davidson told Portland State University in an interview decades later, “I didn’t hesitate, and as luck would have it, I didn’t have any competition.” The one bit of guidance that Knight gave her to go on when drawing up proposed graphics for the company: “He wanted [the logo] to look like speed.”

In light of an impending deadline, which was tied to the printing of the company’s new shoeboxes, Davidson presented a handful of potential logo designs to Knight, Bowerman, and a handful of people that the young company’s founders had enlisted to give their input. Knight, who would make the ultimate decision, was not really drawn to any of them. Yet, he returned to one, a check mark-like swoosh, and in light of the crunch for time, gave it the go-ahead despite his initial reservations.

“I don’t love it, but maybe it will grow on me,” he famously said at the time. That logo is now one of the most famous in the world.

Since Beaverton, Oregon-based Nike’s swoosh was her first professional design job, Davidson did not know what to charge for her work. So, she opted for a rate of $2 for each of the 17.5 hours she spent on the various logos, and sent the Nike co-founders a bill for $35, a sum that, if adjusted for inflation, would amount to nearly $221 in 2019, a virtual steal compared to the reported $1 million that Pepsi paid to the now-defunct Arnell Group in 2009 for its logo or the whopping $221 million that oil company BP spent to reformulate and roll out its branding in 2000.

Interestingly enough, it would be revealed years later that Davidson was ultimately compensated quite a bit more than that initial $35. Speaking at a Nike event in 2010, Knight told shareholders that when Nike listed on the New York Stock Exchange in December 1980, “We called [Davidson] back up and gave her 500 shares of stock, which she has never sold, and is [now] worth close to $1 million.”

In terms of the logo itself, counsel for Nike wasted little time filing an initial application to register the design with the U.S. Patent and Trademark in January 1972, just over six months after Nike claims that it used the logo on athletic shoes (in commerce) for the very first time. The trademark registration would be issued to Beaverton-based BRS, INC. – Blue Ribbon Sports, Inc. – two years later, and the mark would be used – and the seemingly countless infringing uses, policed – consistently for the next 45 years and likely, for decades still to come. (Also among Nike’s 800-plus U.S.-registered trademarks, the word “Swoosh,” which counsel for Nike first filed to register in 1981 and received a registration for – for use in connection with footwear – in 1982).

As for value of Nike’s swoosh logo mark, it has consistently been characterized as one of the most recognizable – and thus, valuable – logos in the world. As such, the swoosh logo, along with Nike’s trademark-protected name, are two of the most important assets of the Nike brand, which is worth a whopping $36.8 billion, according to Forbes’ “World’s Most Valuable Brands” list.

London-based business valuation consultancy Brand Finance similarly quantifies the value of companies from a branding perspective (i.e., as distinct from their pure financials and market capitalization) on an annual basis. Assigning a “brand value” to companies, Brand Finance aims to quantify “the value of the [brand’s] trademark and associated marketing intellectual property within the branded business,” including intangible assets that are “intended to identify goods, services or entities, [thereby], create distinctive images and associations in the minds of stakeholders, and generate economic benefits.”

For 2019, it put Nike’s brand value – which is, in large part, driven by its swoosh mark – at $32.4 billion, thereby, situating the 55-year old company quite a bit more favorably than the likes of fast fashion behemoth Zara (with a brand value of $18.4 billion), arch-rival adidas ($16.6 billion), and luxury entities, such as Louis Vuitton ($13.5 billion), Rolex ($8.04 billion), Gucci ($10.2 billion), and Hermès ($10.9 billion), among others.

Aside from the enormous dollar value that could very well be assigned to Nike’s world-famous swoosh (although, valuing individual trademarks tends to be something of a difficult science), Nike – which continues to keep hold of the title of the most valuable apparel/footwear brands in the world – garners another significant benefit from the mark, an intangible one. The mark, itself, communicates the core principles and vision of the Nike brand, which is in many cases precisely what consumers are buying into when they purchase a Nike shoe or garment and what helps to set the company’s products apart from largely similar offerings from its competitors.

They are purchasing the shoe or the hoodie or the hat, and any practical perks that come with them, and there are points to be made about the level of quality, and the consumer experience elements associated with Nike and its offerings, but potentially in equal part, consumers are also buying into the story-telling elements of the Nike brand, i.e., it core values and mission, when they opt for a swoosh-adorned product in much the same way that a consumer chooses a luxury logo-covered bag or logo-adorned pair of glasses.

In this sense, the swoosh is part of a far larger picture, and a price cannot be put on the sheer value of that goodwill, unless it can: $153 billion, Nike’s current market cap.